The “Windsor” Enfield In 1853

The “Windsor” Enfield In 1853, the British Board of Ordnance adopted a revolutionary new reduced caliber, rifled long arm for general issue to the British military. While still a muzzleloading, percussion ignition gun, the new Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket was .577 caliber with a 39" barrel, rifled with three-grooves of progressive depth. Technically, the British military had adopted rifled arms for general issue in 1851 with the acceptance of the Pattern 1851 Minié Rifle, but that was still a very large bore arm with a .708" bore, not a significant reduction from the .75" bore that had been used with the two prior percussion musket models, the Patterns 1839 and 1842.

The Pattern 1853 was a radical style change for the British because the barrel was secured by three clamping bands and the breech plug tang screw, rather than the pins or wedges, which had been used to secure British musket barrels to their stocks for well over a century. Interestingly, it was American firms that the British turned to for producing the manufacturing equipment necessary to build the new guns and modernize the Royal Small Arms Manufactory at Enfield Lock; often referred to simply as “Enfield” or RSAF. Some twenty-three stock making machines were ordered from the NP Ames Company in 1854 and in the summer of that year an additional one hundred fifty gun making machines were ordered from Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vt. Robbins & Lawrence had been a leader in the push toward the “American System” of production, which involved producing items with interchangeable parts in an assembly line fashion.

The British intended the new Pattern 1853 Enfields, which were to be produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory, to have interchangeable parts based upon the “American System.” American machinery installed at the Royal Small Arms Factory was up and running by March 1856. Interestingly, it was former Harpers Ferry Acting Master Armorer James Burton who the British hired to oversee installation of the new equipment and manufacturing of the new arms at Enfield. Burton had taken a job with Ames in 1854, but in 1855 entered into a five year agreement to work for the British at Enfield. Burton would eventually return to the United States at the end of his British employment and become supervisor of the newly reopened Richmond Arsenal for the state of Virginia (formerly the Virginia Manufactory).

After secession, and establishment of the Confederate States of America, Burton established the Macon Armory and helped acquire English machinery for manufacturing arms in the South. In October 1853, the Crimean War erupted, drawing the British military into an international conflict they were ill prepared and equipped to fight. Initially the British troops were deployed with older pattern smoothbore muskets and the recently adopted Pattern 1851 Minié Rifle. However, it soon became clear that the superiority of the new Pattern 1853 design would be a great advantage to British troops in the field.

With a newly adopted firearm about to start production at RSAF, the Board of Ordnance did what they had always done in times of emergency; they turned to the London and Birmingham arms trade to manufacture the new pattern rifle musket. When the trade could not produce the number of arms needed, the British started looking for additional sources to produce firearms during the Crimean War, including foreign gunmakers in Liège (Belgium), France, and America. Due to the intimate knowledge that Robbins & Lawrence had with making Enfield Rifle Musket production machinery, the firm was a logical choice for the British looking for supplemental firearm sources during the Crimean War.

In February 1855, the English Board of Ordnance contracted with the New York based firm of Fox, Henderson & Company to supply some twenty-five thousand Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets. Fox, Henderson & Co subsequently contracted with Robbins & Lawrence to produce the firearms.

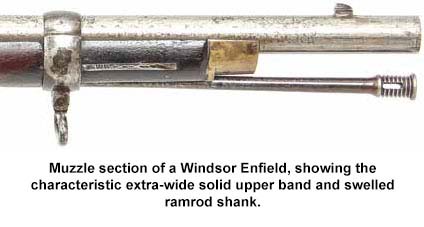

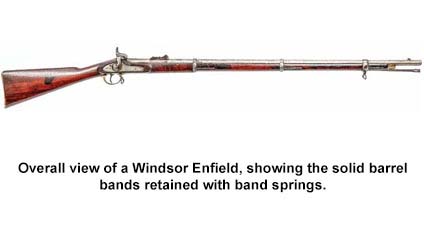

The musket built in the United States by the firm of Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vt., was the pattern of Enfield known to collectors and researchers as the “Type II” Pattern 1853 Rifle Musket. The primary feature separating the Type II P1853 from the much more commonly encountered Type III P1853 (the version primarily used during the American Civil War), was the use of solid barrel bands retained by band springs, rather than the screw-fastened, Palmer patent, clamping bands. Additionally, the ramrod of the Type II was retained in the stock by a swell near the tip, similar to the U.S. M1855 and M1861 rammers, while the Type III Enfields had their ramrods retained by a spring-loaded “spoon” in the stock.

Assuming that the order for 25,000 guns was only the beginning of what would be additional large orders for the British military due to the Crimean conflict, Robbins & Lawrence invested substantial amounts of money expanding their production facilities in Windsor, Vt., and built a second factory in Hartford, Conn. They also invested heavily in new machinery and an expanded workforce. All this was done with borrowed money, much of it from Fox, Henderson & Co., as well as other creditors.

This rapid expansion based on credit would cause the ruin of the company. Production of the Enfields by Robbins & Lawrence was initially delayed by the fact that the sample guns sent to the firm to produce the inspection gauges were handmade and not interchangeable gun parts from Enfield. As a result, the guns were not dimensionally similar enough to produce the accurate production gauges that were required.

The British then sent a set of wooden inspection gauges to Robbins & Lawrence, but the trans-Atlantic voyage warped them enough to make them no longer usable. In the end, Robbins & Lawrence were forced to produce their own samples, machinery, and gauges from technical drawings in order to start production.

The original contract had required the delivery of 650 guns per week, starting in June 1855, with monthly delivery totals of 2,600 guns. Due to the numerous production delays and setbacks, the first Enfields were not delivered until December 1855, some six months late. Even then, the deliveries were only at a rate of 640 per month, less than a quarter of the required delivery rate!

By the end of 1856, production had increased to some 2,000 per month, but had still not reached the original contractual output. With the conclusion of the Crimean War at the end of March 1856, the British Government’s pressing need for arms ended. As a result, the incomplete arms contract with Fox, Henderson & Co was promptly cancelled.

Due to the late (and slow) delivery of arms by Robbins & Lawrence, both companies had been in default since the prior year, so the cancellation should not have been unexpected. In October 1856, about six months after the contact cancellation, Robbins & Lawrence declared bankruptcy. Approximately 10,400 Type II P1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets of which an unknown number were actually delivered to the British government were manufactured prior to the Robbins & Lawrence bankruptcy.

The Windsor Enfields that were delivered to the British were quickly deemed 2nd Class since they were of an obsolete pattern (Type II instead of the more current Type III) and most appear to have been sent to arm colonial and British Empire forces around the globe, from Canada to India, and everywhere in between.

An additional 5,600 were completed by the newly established Vermont Arms Company, which had been set up by the creditors of Robbins & Lawrence to assemble guns from left over parts on hand, and to fabricate new ones as needed. Fox, Henderson & Co agreed to accept these 5,600 guns assembled by Vermont Arms as payment for their credit interest in the now bankrupt company.

In 1858, The Vermont Arms Company also failed, and the remaining inventory and assets were sold at auction. The Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company purchased the Hartford Factory while the Windsor, Vt., factory was acquired by E.G. Lamson and Able Goodnow. Lamson and Goodnow would later go on to produce U.S. M1861 Special Model Muskets at this facility under the name of Lamson, Goodnow & Yale (LG&Y) during the Civil War.

At the same time the factories were sold, the machinery and many parts for as yet unbuilt guns were sold at auction. Many of these parts ended up in the possession of the Whitney Arms Company and were used in producing their very rare and odd “good and serviceable” arms of Enfield pattern. It is noted in period documents that Whitney acquired enough parts to fabricate some 4,000 arms at the auction, and also acquired a rifling machine. There is some indication that a small number of the completed Robbins & Lawrence Enfields received by Fox, Henderson & Company were sold to Mexican Nationalists who were revolting against the rule of Emperor Maximillian I in Mexico.

New York merchants like Fox, Henderson & Company also sold many completed arms to Southern states during 1860 and early 1861. The states purchased the arms in preparation for the looming American Civil War. Researchers have determined that at least some “Windsor Enfields” were purchased by the State of South Carolina, with the possibility that as many as 710 were acquired by that state. On Jan. 21, 1861, 38 cases of rifled muskets being shipped from New York City to Alabama and Georgia were impounded by the New York Police Department. These guns were packed 20 to a case, with 28 cases destined for Alabama and ten headed for Georgia.

Period documents note that the 28 cases headed to Alabama were “Robbins & Lawrence Enfields.” The description of the Georgia guns is not so accurate, but does note that the some arms were marked with “CROWN over A” over an inspection mark number on the breech and other parts. These were the marks of the British Board of Ordnance subinspectors who had inspected completed component parts at the Robbins & Lawrence factory, prior the guns being assembled into finished arms.

While it is not known how many Georgia regiments received Robbins & Lawrence guns, period documents and images indicate that the militia company known as the Rome Light Guards (later to be Company A of the 8th Ga. Infantry) were armed with at least some “Windsor Enfields.” Additional indications of Southern use appeared in a March 1861 advertisement from a company in Petersburg, Va., listing 100 “Windsor Enfields” for sale.

A letter from Confederate Lt. J. Wilcox Brown, dated June 1, 1863, lists “Windsor” among maker marks he noted on the locks of Enfield arms being repaired at the Richmond Artillery Workshop. He also noted Enfields marked “Tower, Bond, Carr, Barnett & Greener.” These period accounts make it clear that a significant number of “Windsor” Enfields ended up in Southern hands during the American Civil War.

This seems to explain the overall scarcity of the “Windsor” Enfields these days, as many later production, non-British military arms, ended up seeing hard service with Confederate soldiers.

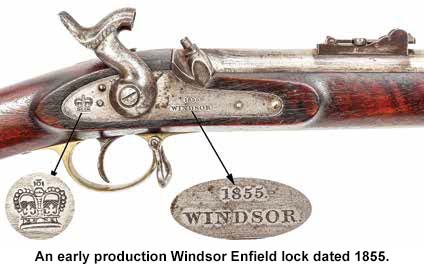

While it can be difficult to determine if a Windsor Enfield saw Confederate or other Civil War service, some basic rules of thumb can be applied. Locks with dates of 1857 and 1858 were definitely produced after the British contract cancellation, which means that they could not have seen British use and as such are candidates for Civil War use. Realistically, most 1856 dated guns were unlikely to have been shipped to England. The contract was cancelled in March of that year and it is not likely that a large number of 1856 dated locks were assembled into completed guns before the contract was cancelled. The majority of arms seeing British service were certainly dated 1855, although that date does not rule the weapon out as a Civil War gun, as not all completed arms were accepted by British arms viewers. The British military accepted guns would also show British sub-inspection marks throughout, including the aforementioned Crown/A/# inspection marks on many small parts and British military proof marks on the barrels.

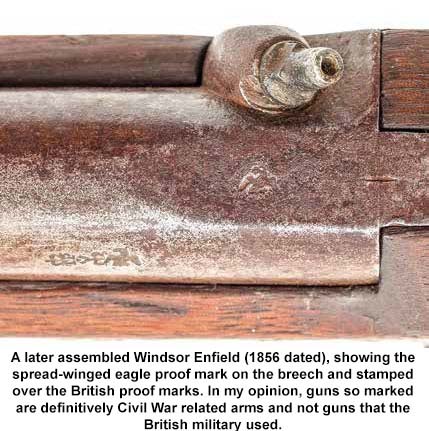

However, the presence of some (or many) British inspection marks does not rule the gun out for Civil War service either, as many completed parts were inspected by the British viewers and appropriately marked, but were never assembled into complete arms prior to the contract cancellation. One mark that does appear to be from the post British contract, Vermont Arms period, is a spread-winged eagle proof mark on the breeches of barrels. This mark should be considered as indicating that the gun that was completed and sold after the British contract was cancelled and thus almost certainly saw Civil War service. However, British inspected barrels also saw use on some Civil War arms.

In the end, only the presence of British military rack and issue marks on the buttplate tangs or storekeeper marks in the stocks of Windsor Enfields can be considered definitive evidence that a gun did not see Civil War service.

Tim Prince is a full-time dealer in fine & collectible military arms from the Colonial Period through WWII. He operates College Hill Arsenal, a web-based antique arms retail site. A long time collector & researcher, Tim has been a contributing author to two major book projects about Civil War era arms including The English Connection and a new book on southern retailer marked and Confederate used shotguns. Tim is also a featured Arms & Militaria appraiser on the PBS Series Antiques Roadshow.