All Blogs

Home Blog

Lindsay’s “Double Musket”

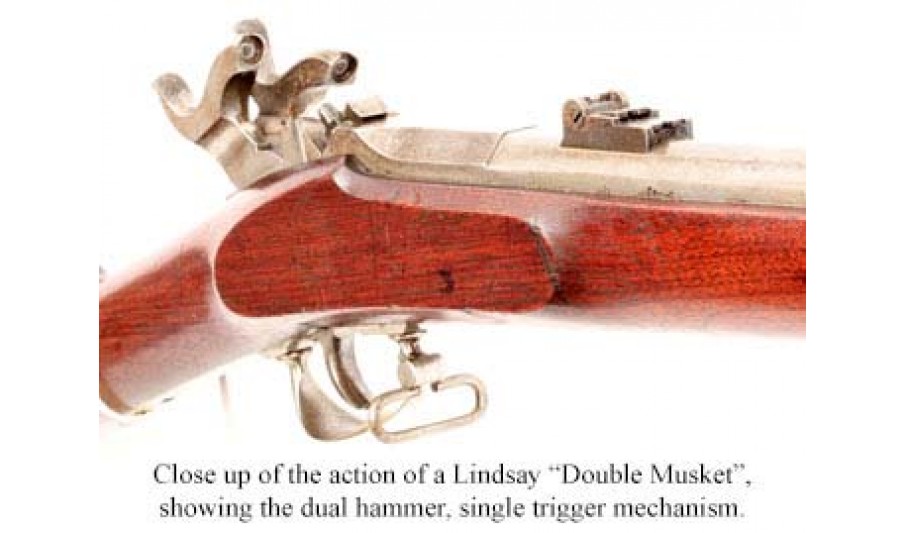

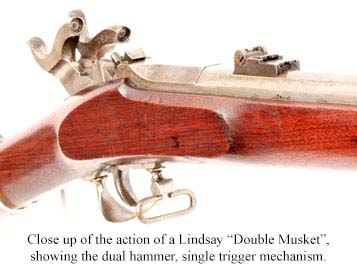

On October 9, 1860 John Parker Lindsay of New York City received US Patent #30,332 for “improvement in locks for fire-arms.” The patent covered a unique, superimposed muzzleloading percussion firearms action that combined two hammers, a single trigger and two loads, fired from a single barrel. Lindsay’s patent actually claimed that his “new and useful Improvement in Locks for Fire-Arms” could be applied when “two or more hammers are used”. The primary patent coverage was for the firing mechanism, which combined a single trigger and two (or more) hammers. It is possible that Lindsay developed the concept for his mechanism while working with New York gun maker John Walch circa 1859, who had patented a double-hammer percussion revolver that utilized superimposed loads to double the number of rounds fired from a percussion revolver.

Lindsay’s mechanism allowed two hammers to be fired sequentially from a single trigger. The auto-selecting single trigger would always release the right hammer first and the left hammer second on two consecutive pulls; not unlike a modern double-barreled sporting shotgun with a single trigger. Using his superimposed chamber concept, with one load on top of the other in the breech, the first hammer would fire the front chamber of the gun, and the second hammer would fire the rear chamber.

In 1861, Lindsay relocated from New York City to New Haven, CT. and began to actively produce and promote his unique firearms. Lindsay initially applied his concept to a series of handguns that he marketed as the “Young America” line. The guns were produced for Lindsay circa 1860-62 by the Union Knife Company of Naugatuck, CT. Two variations were manufactured in .41 caliber (totaling less than three hundred guns), and another one hundred were produced in .45 caliber. However, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Lindsay became intrigued with applying his concept to a .58 caliber rifle musket and obtaining a US military contract.

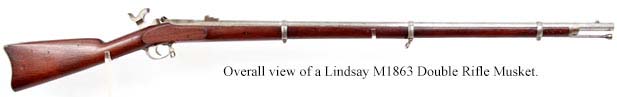

Using the superimposed load concept, in combination with his patented double-hammer/single-trigger system, Lindsay produced a sample musket that effectively doubled the firepower of the average soldier in combat, as the design could be fired twice before it was reloaded. However, the design allowed the gun to retain a single barrel, keeping nearly as light and handy as a standard percussion rifle musket. During the summer of 1863, Lindsay worked in vein to obtain an Ordnance Department contract for his “Double Musket”. However, Chief of Ordnance James Ripley was unimpressed and no orders were forthcoming. This was despite the fact that a trial musket, tested at West Point, had been found quite satisfactory, with the reviewing officer noting that “In my opinion, the invention is a success.” In September 1863, Ripley was replaced by General George Ramsay, and Lindsay saw an opportunity to press his case again. In October, he submitted an improved version of the musket that had been tested at West Point, and managed to obtain a small contract to provide 1,000 of his patented double rifle muskets. The contact was officially issued in mid-December, with deliveries due to commence in April of 1864, at a price of $25 each.

As with his pistol project, Lindsay had to turn to outside manufactures to actually produce the firearms. He appears to have relied upon his old contractor, the Union Knife Company, to manufacture the receiver and mechanical action of the gun, although some sources think that Lindsay may have manufactured this complicated lock work himself. The guns themselves were produced by Samuel Norris of Springfield, MA. Norris had previously produced US M1863 Rifle Muskets for the state of Massachusetts, but that contract was at an end and no further contracts appeared to be forthcoming. As such, Norris was more than happy to take on the production of the Lindsay muskets, mating the Lindsay provided receivers with the rest of the components necessary to produce the completed rifle musket. Due to various delays, the guns were not available for delivery in April of 1864, as had been specified in the contract, and Lindsay had to request a contract extension. The production issues were resolved, and the entire order of 1,000 guns was delivered and accepted on August 16, 1864. Less than one month later, on September 12, 1864 half of the muskets were issued for field trials.

Lindsay Double Rifle Muskets were issued to the 5th, 16th & 23rd Michigan Volunteer Infantry regiments, as well as to the 9th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. The 16th Michigan received 166 of the guns, and used them at the battle of Peebles’ Farm, which was fought at part of the Petersburg Campaign from September 30 through October 2, 1864. The other regiments all received 83 guns each. Reports from both the 16th MI and 9th NH indicate that some catastrophic failures occurred in the field, causing both injuries and deaths.

The failures of the guns in the field were completely understandable. While the superimposed loading concept worked fine in theory, it did not work so well in the field in a combat situation. The system relied upon very careful loading, with the bullet from the rear most charge preventing that second powder charge from going off when the first chamber was fired. This did not always happen (especially when the musket was loaded quickly or under duress), and would result in both chambers detonating simultaneously; usually with disastrous results for both the musket and the shooter. The other problem, which was equally disastrous, was that the long flash channel to the forward chamber could become fouled, preventing it from discharging. When the second charge was fired, with the first charge still blocking the barrel, the results were often catastrophic as well. Either problem ensured a bad day for the gun and the soldier using it, and as a result the weapons were universally despised by the men they were issued to. Due to the various calamities relating to the use of the double musket in the field, the guns were fairly quickly condemned and withdrawn from service.

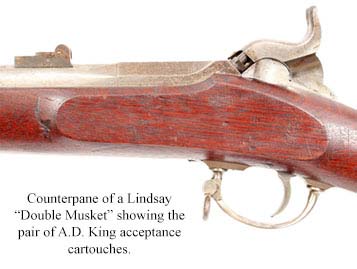

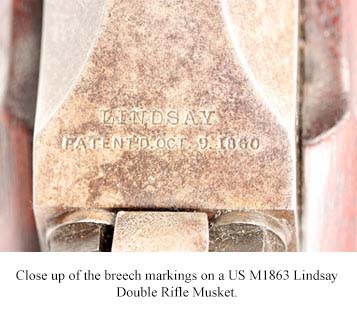

The US M1863 Lindsay Patent Double Rifle Musket had the same basic profile of the US M1861, M1863 and M1864 rifle muskets then in service. In fact, other than the special lock mechanism and breech, the majority of the parts were the same as found on US M1863 Rifle Muskets; this is not surprising, as Norris likely had lots of spare parts from his M1863 contract on hand. The gun was .58 caliber, with a barrel that measured 41 1/8” length rather than the usual 40” of the M1863 rifle musket. This was due primarily to the larger breech to accommodate the two superimposed loads. The top of the breech was marked in two lines, reading LINDSAY over PATENT’D OCT. 9. 1860. Due to the nature of the lock mechanism, the walnut stock has no external lock plate on the obverse, but still retained the same silhouette as the M1863 rifle musket. The barrel was secured to the stock with three rounded clamping barrel bands and a screw at the end of the extended breech tang. All metal parts were finished in the white and polished to “National Armory Bright”. Civilian Ordnance Department sub-inspector Andrew D. King inspected all examples of these muskets that I have ever encountered, with a pair of cartouches on the counterpane of the musket. King also sub-inspected the breech and trigger systems of the guns, with the balance of the components carrying various sub-inspector marks from other viewers. The standard US M1861 pattern rear sight was used on the gun and the front sight doubled as a lug to accept the standard US M1855 angular socket bayonet. Sling swivels were attached to the middle barrel band and to the forward bow of the triggerguard.

Due to the relatively low production figures, and the fact that some of the guns actually destroyed themselves in the field, the Lindsay Double Musket is a fairly scarce item on the collector market today. It is also possible that some of the guns were intentionally destroyed by the soldiers in the field to make sure that they would not have to use them again in the future. Although Lindsay’s loading concept was a dismal failure, his auto-selecting trigger mechanism lives on and continues to be used in many double-barreled sporting shotguns to this day.

Whitney Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets

The American-made Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket contract that was the downfall of the Robbins & Lawrence firearms manufacturing company. As part of the bankruptcy process, many assets of the defunct firm were sold at auction, with one of the largest buyers being Eli Whitney Jr., the principle of the Whitneyville Armory. As previouslt noted, Whitney obtained a large number of gun parts as well as some machinery at this auction.

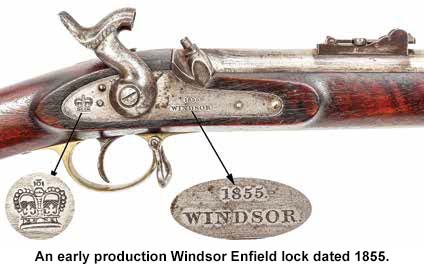

The “Windsor” Enfield In 1853

The “Windsor” Enfield In 1853, the British Board of Ordnance adopted a revolutionary new reduced caliber, rifled long arm for general issue to the British military. While still a muzzleloading, percussion ignition gun, the new Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket was .577 caliber with a 39" barrel, rifled with three-grooves of progressive depth. Technically, the British military had adopted rifled arms for general issue in 1851 with the acceptance of the Pattern 1851 Minié Rifle, but that was still a very large bore arm with a .708" bore, not a significant reduction from the .75" bore that had been used with the two prior percussion musket models, the Patterns 1839 and 1842.

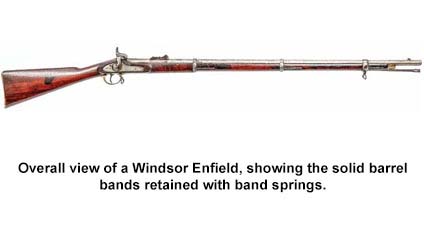

The Pattern 1853 was a radical style change for the British because the barrel was secured by three clamping bands and the breech plug tang screw, rather than the pins or wedges, which had been used to secure British musket barrels to their stocks for well over a century. Interestingly, it was American firms that the British turned to for producing the manufacturing equipment necessary to build the new guns and modernize the Royal Small Arms Manufactory at Enfield Lock; often referred to simply as “Enfield” or RSAF. Some twenty-three stock making machines were ordered from the NP Ames Company in 1854 and in the summer of that year an additional one hundred fifty gun making machines were ordered from Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vt. Robbins & Lawrence had been a leader in the push toward the “American System” of production, which involved producing items with interchangeable parts in an assembly line fashion.

The British intended the new Pattern 1853 Enfields, which were to be produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory, to have interchangeable parts based upon the “American System.” American machinery installed at the Royal Small Arms Factory was up and running by March 1856. Interestingly, it was former Harpers Ferry Acting Master Armorer James Burton who the British hired to oversee installation of the new equipment and manufacturing of the new arms at Enfield. Burton had taken a job with Ames in 1854, but in 1855 entered into a five year agreement to work for the British at Enfield. Burton would eventually return to the United States at the end of his British employment and become supervisor of the newly reopened Richmond Arsenal for the state of Virginia (formerly the Virginia Manufactory).

After secession, and establishment of the Confederate States of America, Burton established the Macon Armory and helped acquire English machinery for manufacturing arms in the South. In October 1853, the Crimean War erupted, drawing the British military into an international conflict they were ill prepared and equipped to fight. Initially the British troops were deployed with older pattern smoothbore muskets and the recently adopted Pattern 1851 Minié Rifle. However, it soon became clear that the superiority of the new Pattern 1853 design would be a great advantage to British troops in the field.

With a newly adopted firearm about to start production at RSAF, the Board of Ordnance did what they had always done in times of emergency; they turned to the London and Birmingham arms trade to manufacture the new pattern rifle musket. When the trade could not produce the number of arms needed, the British started looking for additional sources to produce firearms during the Crimean War, including foreign gunmakers in Liège (Belgium), France, and America. Due to the intimate knowledge that Robbins & Lawrence had with making Enfield Rifle Musket production machinery, the firm was a logical choice for the British looking for supplemental firearm sources during the Crimean War.

In February 1855, the English Board of Ordnance contracted with the New York based firm of Fox, Henderson & Company to supply some twenty-five thousand Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets. Fox, Henderson & Co subsequently contracted with Robbins & Lawrence to produce the firearms.

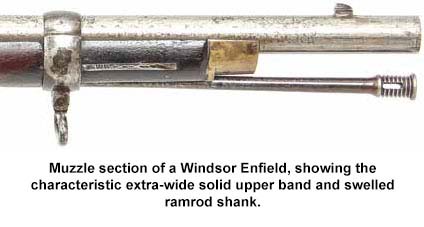

The musket built in the United States by the firm of Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vt., was the pattern of Enfield known to collectors and researchers as the “Type II” Pattern 1853 Rifle Musket. The primary feature separating the Type II P1853 from the much more commonly encountered Type III P1853 (the version primarily used during the American Civil War), was the use of solid barrel bands retained by band springs, rather than the screw-fastened, Palmer patent, clamping bands. Additionally, the ramrod of the Type II was retained in the stock by a swell near the tip, similar to the U.S. M1855 and M1861 rammers, while the Type III Enfields had their ramrods retained by a spring-loaded “spoon” in the stock.

Assuming that the order for 25,000 guns was only the beginning of what would be additional large orders for the British military due to the Crimean conflict, Robbins & Lawrence invested substantial amounts of money expanding their production facilities in Windsor, Vt., and built a second factory in Hartford, Conn. They also invested heavily in new machinery and an expanded workforce. All this was done with borrowed money, much of it from Fox, Henderson & Co., as well as other creditors.

This rapid expansion based on credit would cause the ruin of the company. Production of the Enfields by Robbins & Lawrence was initially delayed by the fact that the sample guns sent to the firm to produce the inspection gauges were handmade and not interchangeable gun parts from Enfield. As a result, the guns were not dimensionally similar enough to produce the accurate production gauges that were required.

The British then sent a set of wooden inspection gauges to Robbins & Lawrence, but the trans-Atlantic voyage warped them enough to make them no longer usable. In the end, Robbins & Lawrence were forced to produce their own samples, machinery, and gauges from technical drawings in order to start production.

The original contract had required the delivery of 650 guns per week, starting in June 1855, with monthly delivery totals of 2,600 guns. Due to the numerous production delays and setbacks, the first Enfields were not delivered until December 1855, some six months late. Even then, the deliveries were only at a rate of 640 per month, less than a quarter of the required delivery rate!

By the end of 1856, production had increased to some 2,000 per month, but had still not reached the original contractual output. With the conclusion of the Crimean War at the end of March 1856, the British Government’s pressing need for arms ended. As a result, the incomplete arms contract with Fox, Henderson & Co was promptly cancelled.

Due to the late (and slow) delivery of arms by Robbins & Lawrence, both companies had been in default since the prior year, so the cancellation should not have been unexpected. In October 1856, about six months after the contact cancellation, Robbins & Lawrence declared bankruptcy. Approximately 10,400 Type II P1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets of which an unknown number were actually delivered to the British government were manufactured prior to the Robbins & Lawrence bankruptcy.

The Windsor Enfields that were delivered to the British were quickly deemed 2nd Class since they were of an obsolete pattern (Type II instead of the more current Type III) and most appear to have been sent to arm colonial and British Empire forces around the globe, from Canada to India, and everywhere in between.

An additional 5,600 were completed by the newly established Vermont Arms Company, which had been set up by the creditors of Robbins & Lawrence to assemble guns from left over parts on hand, and to fabricate new ones as needed. Fox, Henderson & Co agreed to accept these 5,600 guns assembled by Vermont Arms as payment for their credit interest in the now bankrupt company.

In 1858, The Vermont Arms Company also failed, and the remaining inventory and assets were sold at auction. The Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company purchased the Hartford Factory while the Windsor, Vt., factory was acquired by E.G. Lamson and Able Goodnow. Lamson and Goodnow would later go on to produce U.S. M1861 Special Model Muskets at this facility under the name of Lamson, Goodnow & Yale (LG&Y) during the Civil War.

At the same time the factories were sold, the machinery and many parts for as yet unbuilt guns were sold at auction. Many of these parts ended up in the possession of the Whitney Arms Company and were used in producing their very rare and odd “good and serviceable” arms of Enfield pattern. It is noted in period documents that Whitney acquired enough parts to fabricate some 4,000 arms at the auction, and also acquired a rifling machine. There is some indication that a small number of the completed Robbins & Lawrence Enfields received by Fox, Henderson & Company were sold to Mexican Nationalists who were revolting against the rule of Emperor Maximillian I in Mexico.

New York merchants like Fox, Henderson & Company also sold many completed arms to Southern states during 1860 and early 1861. The states purchased the arms in preparation for the looming American Civil War. Researchers have determined that at least some “Windsor Enfields” were purchased by the State of South Carolina, with the possibility that as many as 710 were acquired by that state. On Jan. 21, 1861, 38 cases of rifled muskets being shipped from New York City to Alabama and Georgia were impounded by the New York Police Department. These guns were packed 20 to a case, with 28 cases destined for Alabama and ten headed for Georgia.

Period documents note that the 28 cases headed to Alabama were “Robbins & Lawrence Enfields.” The description of the Georgia guns is not so accurate, but does note that the some arms were marked with “CROWN over A” over an inspection mark number on the breech and other parts. These were the marks of the British Board of Ordnance subinspectors who had inspected completed component parts at the Robbins & Lawrence factory, prior the guns being assembled into finished arms.

While it is not known how many Georgia regiments received Robbins & Lawrence guns, period documents and images indicate that the militia company known as the Rome Light Guards (later to be Company A of the 8th Ga. Infantry) were armed with at least some “Windsor Enfields.” Additional indications of Southern use appeared in a March 1861 advertisement from a company in Petersburg, Va., listing 100 “Windsor Enfields” for sale.

A letter from Confederate Lt. J. Wilcox Brown, dated June 1, 1863, lists “Windsor” among maker marks he noted on the locks of Enfield arms being repaired at the Richmond Artillery Workshop. He also noted Enfields marked “Tower, Bond, Carr, Barnett & Greener.” These period accounts make it clear that a significant number of “Windsor” Enfields ended up in Southern hands during the American Civil War.

This seems to explain the overall scarcity of the “Windsor” Enfields these days, as many later production, non-British military arms, ended up seeing hard service with Confederate soldiers.

While it can be difficult to determine if a Windsor Enfield saw Confederate or other Civil War service, some basic rules of thumb can be applied. Locks with dates of 1857 and 1858 were definitely produced after the British contract cancellation, which means that they could not have seen British use and as such are candidates for Civil War use. Realistically, most 1856 dated guns were unlikely to have been shipped to England. The contract was cancelled in March of that year and it is not likely that a large number of 1856 dated locks were assembled into completed guns before the contract was cancelled. The majority of arms seeing British service were certainly dated 1855, although that date does not rule the weapon out as a Civil War gun, as not all completed arms were accepted by British arms viewers. The British military accepted guns would also show British sub-inspection marks throughout, including the aforementioned Crown/A/# inspection marks on many small parts and British military proof marks on the barrels.

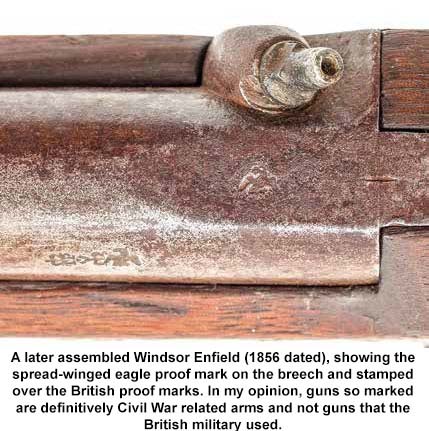

However, the presence of some (or many) British inspection marks does not rule the gun out for Civil War service either, as many completed parts were inspected by the British viewers and appropriately marked, but were never assembled into complete arms prior to the contract cancellation. One mark that does appear to be from the post British contract, Vermont Arms period, is a spread-winged eagle proof mark on the breeches of barrels. This mark should be considered as indicating that the gun that was completed and sold after the British contract was cancelled and thus almost certainly saw Civil War service. However, British inspected barrels also saw use on some Civil War arms.

In the end, only the presence of British military rack and issue marks on the buttplate tangs or storekeeper marks in the stocks of Windsor Enfields can be considered definitive evidence that a gun did not see Civil War service.

Tim Prince is a full-time dealer in fine & collectible military arms from the Colonial Period through WWII. He operates College Hill Arsenal, a web-based antique arms retail site. A long time collector & researcher, Tim has been a contributing author to two major book projects about Civil War era arms including The English Connection and a new book on southern retailer marked and Confederate used shotguns. Tim is also a featured Arms & Militaria appraiser on the PBS Series Antiques Roadshow.

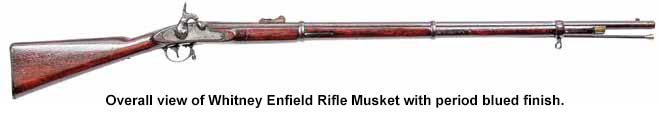

Whitney "Enfield" Pattern Short Rifles

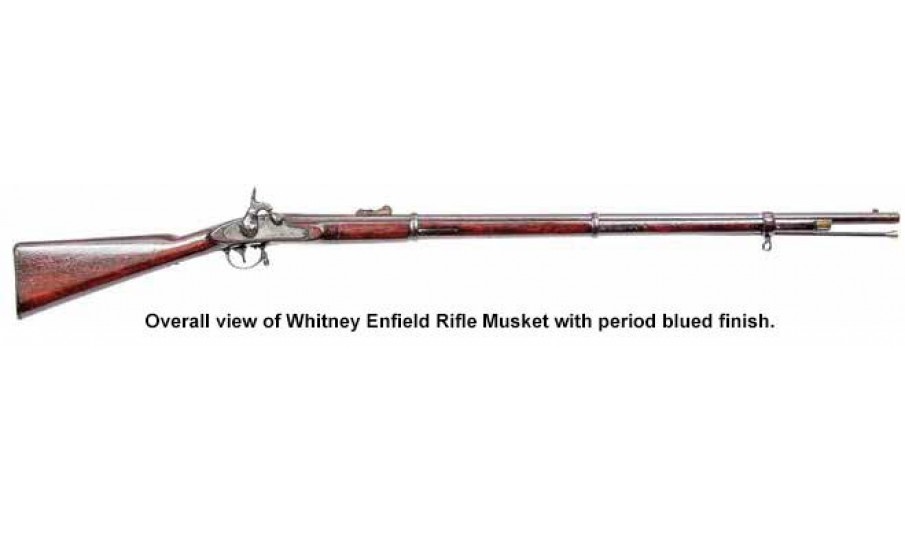

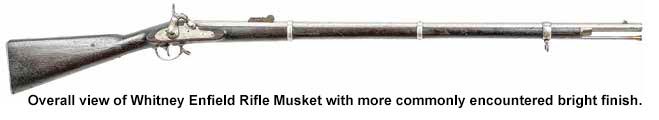

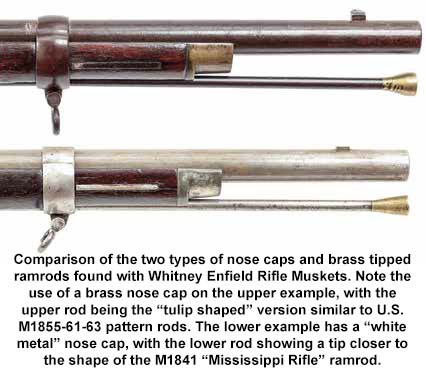

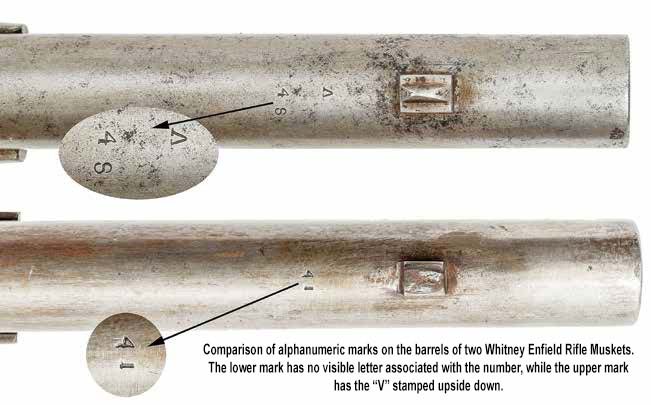

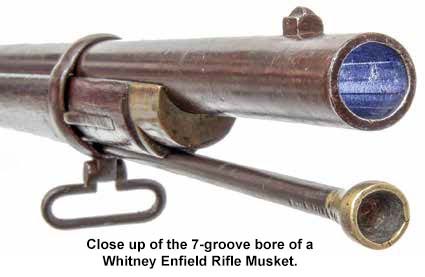

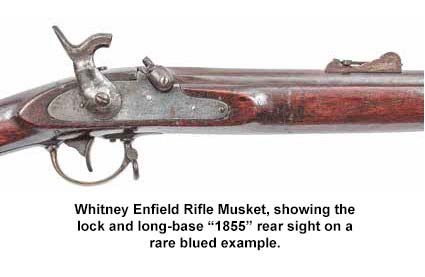

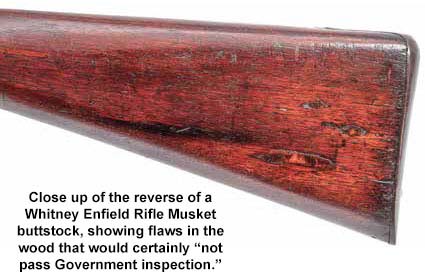

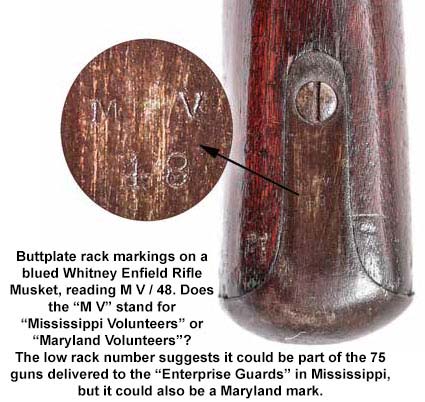

The Short Enfield Rifles produced by the Whitney Arms Company represent another unique series of rifles similar to Whitney’s “Good & Serviceable Arms”. The guns were produced in small batches, in a variety of configurations and utilized a combination of obsolete, condemned, surplus and newly made parts. The Whitney Enfield Rifles were produced in at least four variants, with features such as the presence or absence of a patchbox, the type of rear sight and the type of bayonet lug being the primary differences. In general all of the rifles were loosely based upon the British P-1856 rifle and the US M-1855 rifle. Collectors have referred to the guns as “Enfields” due to Whitney’s use of Pattern 1853 Type II Enfield style barrel bands on all of the guns Unlike the P-1853 Type III Enfield barrel bands (aka Palmer Patent Clamping Bands) found on most Civil War era Enfields, the Type II bands were solid and were retained by band springs set into the stock. It appears that the early Whitney Enfields used left over barrel bands Crimean War era Enfield contract. Whitney had purchased a huge number of finished and unfinished Enfield parts at auction when Robbins & Lawrence went out of business. The Type II upper band was quite wide and early Whitney Enfields have this type of band. Later Whitney Enfields used a narrower upper band that was likely newly made. All of the Whitney Enfield pattern rifles had .58 caliber barrels that were between 32” and 33” in length and flat, flush-fit locks that were similar to Enfield pattern locks. Like the Whitney M-1855 type rifle muskets, the barrel were marked with an alphanumeric “serial number” near the muzzle. The Type I and Type II rifles included an oval patch box in the obverse buttstock, while the Type III and Type IV rifles did not. The Type I did not accept a bayonet, while the Type II and Type III guns had a saber bayonet lug and the Type IV rifle had a front sight/lug for an angular socket bayonet. Type I rifles typically had fixed rear sights, Type II rifles typically had “long range”, long base ladder rear sights Type III rifles had either the “long range” or the Whitey “mid-range” rear sight and most Type IV rifles had “mid-range” rear sight. The typology of the rifles varies from source to source, but I am relying on George Moller’s “American Military Shoulder Arms, Volume III” as the most current and correct source of information. His categorization is slightly different from that found in Flayderman’s or some other author’s texts. All of the Whitney “Short Enfield Rifles” were produced between 1860 and 1861 and it is estimated that between 775 and 2,000 of all types of Whitney Enfield rifles were produced. Many of the earlier production guns were sold to southern states, prior to the outbreaks of the American Civil War. In 1860, the state of Georgia acquired 250 “Whitney Short Enfield Rifles with Saber Bayonets”. Mississippi also ordered “Whitney Short Enfield Rifles with Saber Bayonets” in late 1860, 140 of which were delivered prior to the outbreak of hostilities. In January of 1861 South Carolina purchased 100 Whitney Short Enfields with oval brass patchboxes. As many as 496 “Whitney’s Short Enfield Rifles with Saber Bayonets” were purchased by the US government in the fall of 1861. These arms were acquired from New York based arms and militaria dealer Schuyler, Hartley & Graham. According to a number of sources, it appears that at least two companies of the 10th Rhode Island Infantry were armed with what Moller classifies as Type III Whitney Enfield Rifles.

This is a VERY FINE condition example of the very scarce Whitney Type III Short Enfield Rifle. It is estimated that no more than 600 of these Type III rifles were produced, and probably less than that. The gun is in very crisp and sharp condition and appears to be 100% complete and correct in every way. The rifle is equipped with the Whitney “mid-range” L-shaped leaf sight and has a saber bayonet lug on the right side of the barrel. The lug is numbered 36, the mating number for the bayonet that had been fit to the rifle. The top of the barrel, near the muzzle is marked with the alphanumeric code E 45. The flush-fit, flat lock plate is marked in a single horizontal line: E. WHITNEY along the lower edge, forward of the hammer. Like most Whitney “Enfields”, the lock is secured by a pair of screws that pass through a pair of Enfield style winged, brass screw escutcheons. The lock operates crisply on all positions and is mechanically excellent. The metal of the gun has been lightly cleaned, and has a medium gun metal gray color, slightly toned down from its original “arsenal bright” polish. The metal is mostly smooth, with some thinly scattered, lightly oxidized pinpricking and peppering present on the barrel and lock. The peppering is slightly heavier in the breech and bolster area and on the lock plate, the result of percussion cap flash. The .58 caliber bore of the 33” rifle barrel is in about VERY GOOD condition and retains strong 7-groove Whitney rifling. The bore is mostly bright, but shows some scattered darker patches and would probably benefit from a good scrubbing. The bore shows light pitting along its entire length, with a few patches of more moderate pitting from about middle to barrel and continuing to the muzzle. The rifle has a US M-1855 rifle type front sight and as previously noted a saber bayonet lug near the muzzle. The original Whitney “mid-range” rear sight is in place on the barrel, but the long aperture leaf has been broken or intentionally cut so that the 300-yard aperture is now the top range of the sight and the upper portion that was graduated to 500 yards is no longer present. This appears to have been this way for a very long time, possibly as far back as the period of use. The sight retains about 50% of its original blued finish. The correct two-piece Whitney Enfield triggerguard is in place, with a brass bow mounted to an iron trigger plate. Both original sling swivels are in place on the rifle and the original Whitney pewter forend cap is present at the end of the stock as well. The original Whitney-style, brass tipped ramrod is present and is full length, retaining good threads on the end. The stock of the rifle rates about FINE and is very crisp and sharp throughout. The stock retains good edges and has very good wood to metal fit. The stock is full-length, and free of any breaks, cracks or repairs. The stock does show a number of bumps, dings and handling marks and mars, but shows no serious damage or abuse. The stock does show a couple of minor wood slivers missing from the edges of the ramrod channel, most noticeably near the forend cap.

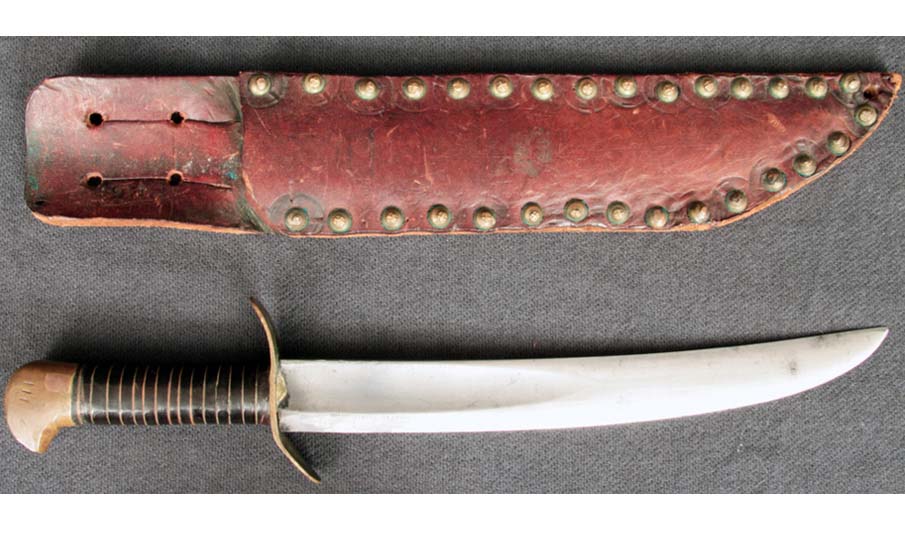

WWII Theater Knife from Civil War Naval Cutlass

This is one of the coolest and most interesting World War II era “Theater Knives” I have ever had the opportunity to offer. It is especially interesting to me, as it combines my love of Civil War era weapons and WWII militaria into a single item. This large and rather intimidating combat knife was crafter from a US Civil War era M-1860 Naval Cutlass. The knife was made from the forward portion of the cutlass blade, is 9 5/8” in length, and retains a little over 4 1/2" of the original cutlass fuller. The overall length of the knife, including the hilt, is just under 13 3/4” in length. The USN M-1860 cutlass was the last of the 19th Century small arms to see service with the US Navy, and they were still in limited service in the arms lockers of some World War II US Navy ships. In fact a WWII US Navy veteran sold a M-1860 cutlass to a friend of mine a few years ago and recalled that he had used the cutlass to fend off sharks for several hours after his ship, the destroyer USS Monssen(DD-436) was sunk in the Pacific! The Monssen was sunk in “Ironbottom Sound” after the November 12-13, 1942 battle of Guadalcanal. This sailor was the last man out of the Number 4 turret on the ship. This bit of first person, anecdotal evidence clearly illustrates that these cutlasses saw at least limited service during WWII. Fighting knives were often manufactured in the machine shops onboard US Navy ships, and this knife was almost certainly made in the Pacific Theater by a Navy machinist. In fact, photos exist of Marines on Guadalcanal carrying theater knives made out of M-1917 Naval Cutlasses, proving that such makeshift sword-knives saw real service in combat situations.