In 1853 the British military decided to establish what would become the Army School of Musketry in Hythe, Kent. The decision that an establishment to produce firearms instructors was needed was a direct result of the recent innovations in firearms design that had been adopted by the British Army some two years earlier. In 1851, the Pattern 1851 Mini” Rifle was adopted and for the first time all line infantry regiments were to be issued rifled arms. Prior to this, the line infantry had fought for more than two centuries with the smoothbore muskets, first with flintlock batteries and later with percussion locks. In both cases the tactics revolved around massed volley fire at relatively short distances, as the smoothbore arms, loaded with loosely fitting round ball, were notoriously inaccurate. As a result, there was no need to instruct soldiers in the finer points of aimed fire, but more expeditious to train them in rapid loading in order to maintain sustained fire. The adoption of expanding base ammunition and the Mini” rifle for general use changed all of that, as the firearm was now capable of much greater accuracy and training was required in order for the solider to take advantage of the potential of the new rifled arms. To that end the Musketry School at Hythe was established in 1853, and listed as an operational post the following year. The goal of the school was to instruct both officers and non-commissioned officers in the “black art” of accurate rifle shooting. The course of instruction covered everything from safe gun handling to the mechanics of rapid reloading, the fundamentals of sight picture and trigger press to the more arcane arts of range estimation and determining windage. In fact, the basic fundamentals of drill were stressed so much that many officers and NCOs complained that they spent more time memorizing command sequences than firing a rifle. Further emphasis on the basis that “perfect practice makes perfect” was the stressing of sight picture, trigger control and follow through, with more students complaining that the only live firing they participated in was the “requisite forty rounds at each distance”. The goal of the school was to make competent instructors, who would then return to their regiments and instruct the soldiers under them in the techniques required to be accurate riflemen. This was the beginning of the British Army’s focus on individual aimed fire, a skill that would show its worth during the first months of the First World War, and would allow an out numbered British Expeditionary Force to hold its own against the advances of the Kaiser’s Army.

The first commandant of the School of Musketry was then Colonel (later General) Charles Crawford Hay of the Green Howards (19th Regiment of Foot “ 1st Yorkshire North Riding). Colonel Hay was a talented shot and certainly interested in process of improving the shooting capabilities of both the soldier and the firearm that he carried. Period accounts note that one of Hay’s favorite demonstrations was to “snap shoot” a rifle from the hip, firing at a target 100 yards away, and always hitting “within 3 feet of the bull”. With the adoption of the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle musket in 1853, Hay became intimately involved in the various trials and testing of various features that would eventually be incorporated into the final P-1853 design. Tests performed at the musketry school involved various rifling systems, sight designs, etc. and Hay had a hand in much of it. Hay was also responsible for recommending a shortening of the stock by 1”, reducing the length of pull from 14” to 13”. Hay made is recommendation as early as 1855, but it would be 1859 before the change was accepted and 1860 before the shorter stock pattern was officially sent to the various contractors producing P-1853 Enfields. While the final decision to adopt the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket with a 39” barrel, with a .577 caliber, 3-groove progressive depth rifled bore, with a rate of twist of 1 in 78” provided a very serviceable weapon, Hay felt that it could be improved upon. His experimentations revealed that while the slow 1:78” twist rate was adequate to stabilize the standard British service projectile in a 39” barrel with acceptable accuracy, it provided less stabilization and much less acceptable accuracy in the 33” barrel of the P-1856 “short rifle”. The performance in the 24” long artillery carbine barrel and the 20” cavalry carbine barrel was even worse. Hay’s experimentation revealed that a 1:48” twist rate was much more conducive to accurate shooting and provided very good stabilization to the projectile even in the very short 20” barrel of the cavalry carbine. He also discovered that there was no difference in the velocities achieved by the standard British service musket load from a 39” barrel or a 36” barrel. For centuries the length of a musket barrel had been predicated upon two goals: 1) being long enough with the bayonet attached for a foot solider to unhorse a cavalryman, and 2) being long enough to achieve acceptable muzzle velocity with the powder charge in use. Black powder is an inefficient propellant and it had long been a study to find the best marriage between charge weight and barrel length. Too short a barrel and unburned powder was wasted, tool long a barrel and the charge fully combusted long before the projectile left the barrel. Both situations were inefficient. By the mid-19th century the chemistry of powder manufacture had improved enough that a shorter barrel could still effectively burn the powder charge, and Hay determined that shortening the barrel by 3” on the rifle musket did not in any way affect velocity or accuracy, but it did reduce the weight of the firearm slightly and make it easier to handle. There is probably the potential that Hay thought that this “medium” length between the 39” barreled “Long Enfield” and the 33” barreled “Short Enfield” might allow for a single model of long arm to serve the needs of troops that now carried two different patterns of weapons. Hay’s additional testing revealed that the rear sight of the P-1853 Enfield Rifle Musket was too close to the eye for good focusing. In fact this problem had been noted when developing the P-1856 rifle, and as a result the rear sights of the rifles were placed further forward, immediately behind the rear barrel band. Hay further suggested replacing the brass furniture on the P-1853 with sturdier “gun metal” (bronze). The final result of Colonel Hay’s testing and experimentation was the Hay Pattern Enfield, known colloquially as the “Medium Enfield”. The gun has a 36” barrel, secured by 3” barrel bands, a .577 bore with 1:48” progressive depth rifling a rear sight graduated to 1,150 yards and placed further forward on the barrel and furniture (buttplate, triggerguard, nose cap and side nail cups) of gun metal. Because the gun was 3” shorter, the lower sling swivel was moved from the front bow of the triggerguard as it was on the “Long Enfield” rifle musket to the rear of the triggerguard on an extended triggerguard plate, as it was on the “Short Enfield” rifle. Despite the fact that Hay’s design was demonstrably more accurate than the standard Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket, it was not accepted by the Board of Ordnance as an official pattern and was never taken into service for field trials. Even though Hay was certainly in a position to push the issue, he was after all the Inspector General of Musketry from 1854-1867, he appears to have let the issue lie. However, those in the know appreciated the substantial improvements made to the P-1853 design and some commercial makers manufactured Hay pattern Enfields for private sale. The variant was certainly popular with dedicated target shooters in the Volunteer movement in England. In 1865 the Colonial Government in New Zealand attempted to purchase some 5,000 Long Enfield rifle muskets and bayonets to arm the newly formed Colonial Defense Force, which was combating the local Maori tribesmen. However, they found that the guns were not readily available in England, probably due to American Civil War production contracts. The purchasing agent suggested acquiring the Hay Pattern Enfield from Isaac Hollis & Sons (previously Hollis & Sheath), and the deal was concluded. The New Zealand government was so happy with the purchase that they soon ordered another 5,000 guns, but Hollis was unable to deliver due to backlogs, and Calisher & Terry completed the second contract for Hay Pattern Enfields for New Zealand. These two orders for 10,000 Hay Pattern Enfields constitute the only known large purchases of the Hay Enfield. All other production was on a very small scale and limited to individual or possibly small group purchases by members of the British Volunteer movement and target shooters. Even though the Hay Pattern Enfield was the most accurate and probably the best conceived variant of the Enfield family of percussion long arms, it was never officially adopted for British military service and saw only very limited production, making it one of the rarest of the Enfield variants for a collector to find today. It should be worth noting that while rumors have swirled for years about possible Civil War use of Hay Pattern Enfields, there is absolutely no documentation that I am aware of that in any way suggests the purchase of Hay Pattern “Medium Enfields’ by either the North or South. While it is certainly possible that a few were acquired from local gun shops or makers by speculators during the early days of the war (Grazebrook certainly sold Volunteer pattern short rifles to the Confederacy during 1861), it remains highly unlikely that the most refined variant of the Enfield ever saw Civil War service.

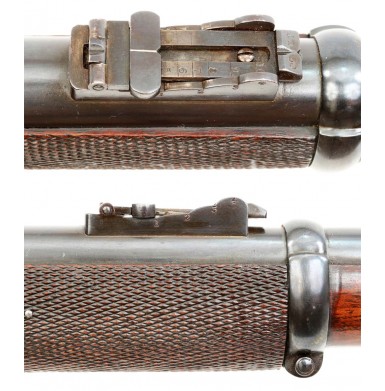

Offered here is a NEAR MINT example of the very scarce Hay Pattern “Medium” Enfield. The rifle is not one of the 10,000 New Zealand contract guns, but rather appears to be a Volunteer gun, commissioned by an English target shooter circa 1857-1861. The rifle was produced by the manufacturer most associated with the Hay Pattern, Hollis & Sheath of Birmingham. The firm became Isaac Hollis & Son in 1861, and it was from this latter day incarnation of the company that New Zealand acquired their first 5,000 Hay Pattern Enfields. The rifle conforms to the Hay Pattern specifications in all ways with the exception of the furniture, which is iron rather than gun metal. The rifle is engraved on the lock, forward of the hammer HOLLIS & SHEATH and in a single line on top of the breech from the nocksform to the rear sight:

HOLLIS & SHEATH . MAKER’s TO HER MAJESTY’s WAR DEPARTMENT .

The left of the breech is marked with the usual Birmingham commercial Provisional Proof, View, Definitive Proof marks as well a pair of gauge (caliber) marks. The first gauge mark reads only “5” instead of the expected “25”, but the second is correctly stamped “25”, indicating .577 caliber. A small German silver oval escutcheon is set into the toe of the stock, behind the triggerguard tang, and is engraved with a set of intertwined script initials that appear to read G H V R. There are no other external markings, other than the graduations on the base and ladder of the rear sight, which is correctly marked from 100-400 yards on the base and from 500 to 1,150 yards on the ladder. The 36” long, round barrel terminates in a hooked breech and is rifled with three grooves with the Hay Pattern 1:48” rate of twist. The bottom of the barrel is marked with the name of the Birmingham barrel maker JOHN CLIVE and is also stamped with the initials G H V R followed by the number 1. The interior of the lock is stamped H&S for Hollis & Sheath. The initials are followed by the number 1 on the mainspring boss stud. This same 1 is also found on the inside of the hammer neck. The interior of the lock mortise is also stamped H&S for Hollis & Sheath, followed by the number 1 which is stamped sideways. The barrel channel bears the same initial stamping, along with a “1”, and with the additional number 34 further down the channel. It appears that the rifle was manufactured for a customer with the initials “G H V R”, as they are marked both under the barrel and on the escutcheon, and the assembly number for the rifle is “1”, as it appears on most of the major components. While the rifle is not dated, we can assume it was produced circa 1858-61, as Hay’s experiments were primarily during 1857 and his resultant design is often referred to as the Hay Pattern 1858, an inaccurate appellation, as only official British military arms would receive a “pattern” designation. As Hollis & Sheath became Isaac Hollis & Son in 1861, it seems likely the rifle was manufactured prior to that name change.

As noted earlier the gun is in about NEAR MINT condition and retains about 95%+ of its original deep, dark British blue on the barrel, and a similar amount on the barrel bands. The barrel shows only the most minor loss and thinning due to age, handling and light use. There is one small patch of finish that has been scraped off the barrel, just forward of the rear barrel band, which might be from a handling mishap. This is quite minor, but is mentioned for exactness as the rifle is in such outstanding condition. The case hardened lock and iron furniture have a smoky slivery gray patina with hints of bluish color and show only traces of their mottling. These parts have all faded with time to a smooth mottled gray patina. The lock and standing breech show wispy traces of darker mottled grays over the silvery base color with a little bit of vivid color still present at the center of the lock were the hammer neck protected the finish from oxidation. The screws all retain nearly all of their original blued finish and even the rear sight retains about 80%+ of its original finish. The bore of the rifle is pristine and remains brilliant with nearly mint condition rifling. There is no doubt that this rifle is still a tack driver, based solely upon the condition of the bore. The Palmer patent clamping barrel bands all retain their original screw protecting “doughnuts’ at the ends of the screws, and the upper band retains its original sling swivel. The original rear swivel is in place in the toe of the stock near the end of the triggerguard plate. The lock of the rifle is mechanically EXCELLENT and functions smoothly and crisply with a very nice trigger pull. The original rear sight is in place and remains fully functional. The original front sight/ bayonet lug is in place as well. The original ramrod is in the channel under the stock and remains full length with fine threads at the end. An original snap cap (nipple protector) is in place on its chain, attached to the eyelet forward of the triggerguard. The checkered walnut stock is in VERY FINE to NEAR EXCELLENT condition as well. The stock is full length, and solid with no breaks, cracks or repairs noted. The rifle retains the early “Enfield” production 14” length of pull. The stock is checkered at the wrist and forend and the checkering remains very crisp and sharp with only the most minor wear and light softening to the points from handling. The stock does show some lightly scattered minor bumps, dings and mars from handling and storage, but nothing significant and nothing to in any way detract from this really wonderful condition rifle.

All in all this is really an outstanding condition example of an extremely rare Hay Pattern “Medium” Enfield. This gun I in absolutely outstanding condition and is very striking in person. These rifles are rarely encountered for sale as few were manufactured and the survival rate seems to be very small. This is a really fantastic find for the dedicated Enfield collector, as rarely do you have the opportunity to acquire a nearly pristine example of the most refined muzzleloading Enfield rifle musket to be manufactured. For a truly serious black powder target shooter, this might just be the next best thing to finding an original Whitworth for use in a military pattern rifle match. Do not miss your chance to purchase such wonderful example of a very scarce gun.

SOLDTags: Hay, Pattern, Enfield, Outstanding, Scarce