CS Keen, Walker & Company Tilting Breech Carbine

- Product Code: FLA-3146-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

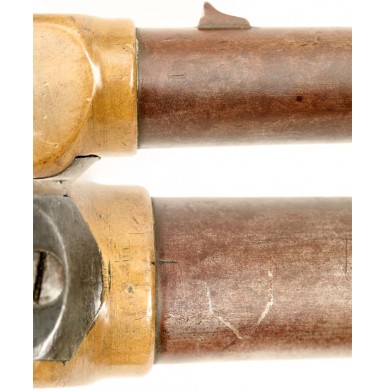

It is interesting that Pittsylvania County, Virginia would become the birthplace for so many intriguing Confederate manufactured arms during the course of the American Civil War. The only “city” or even town of note within the county was Danville, VA, and in that location two Confederate arms making companies would be established; Keen, Walker & Company and Read & Watson. Only twenty miles to the north, in Pittsylvania Courthouse (now named Chatham) the firm of Bilharz, Hall & Company would be established. The irony of the establishment of these three manufactories within some 20 miles of each other is that Bilharz, Hall & Company and Keen, Walker & Company would both produce unique Confederate breechloading carbines on a very limited basis, and Read & Watson would spend their energies altering pre-war US made breechloading Hall rifles to muzzleloaders! Keen, Walker & Company remains an enigmatic firm whose origins are somewhat unclear and even the actual names of who was involved in the company remains up for debate. The “Keen” in the name is not specified in most references, and only one I can find notes that it was an “E.F. Keen”. A search of the 1860 US Census for Pittsylvania County Virginia reveals no one with that name living in the county. However, a substantial number of Keens lived there, and were obviously a prominent family, going back at least three generations in the county. The majority of the Keen heads of household were listed either as “Farmers” or “Tobacconists”, with some of the sons of working age listed as “Factory Hands”. One Keen, a William W. Keen is listed as a farmer with substantial holdings with his real estate valued at $30,800 and the total value of his personal property listed at $69,630! According to www.meauringworth.com the $69,630 from 1860 equates to a 2014 hard currency equivalent of slightly over 2 million dollars, based solely on inflation. From a practical matter of what that amount of money or worth really represented in 1860 versus 2014, the calculator notes that the 1860 personal wealth of $69,630 would be the economic equivalent of over $27 million dollars today. Obviously William. W. Keen was a very wealthy man. Mr. Keen was also one of the 41 shareholders in the Richmond based Union Manufacturing Company, which was established in 1861 to convert flintlock arms to percussion and to try to produce arms as well. I would be more than willing to bet that William W. Keen was the primary shareholder and investor in Keen, Walker & Company, because he had already invested in the Richmond based firearms company, and now had an opportunity to invest “at home”. The identity of the second name in the firm, Walker, is somewhat better known, but the information must be gleaned from multiple sources. James McKenzie Walker was an hotelier in Danville, VA and was listed in the 1860 Census as having real estate valued at $13,900 and having personal property with a value of $15,050. While nowhere near has wealthy as Keen, Walker was obviously another major player in Pittsylvania County. On April 23, 1861 Walker enlisted in Company A of the 18th Virginia Infantry as their 2nd Sergeant. Walker only served a very short time, and on October 5, 1861 he was discharged by special order of the Secretary of War, number 171. I have not been able to find a copy of this order, but it seems almost certain that the discharge had something to do with the formation of Keen, Walker & Company. Murphy & Madaus, in their groundbreaking work Confederate Carbines & Musketoons, reference a letter from a Danville, VA resident dated December 30, 1861 that refers to the establishment of the firm of Keen, Walker & Company, and noting that for that purpose: “Keen has…moved to Danville…he an(d) several others have gorne (sic) in to the Manufacture of Guns for the army. at $40 a peace (sic). (T)hey buy the Barrels in North Carolina an (sic) dress them up an (sic) bore them out an (sic) stock them an (sic) finish off them in Danville all by Machinery.” The original misspellings and grammatical errors have been retained, but clearly the letter suggests the formation of the company was a big deal in Danville in the fall and winter of 1861. The gun that would finally be produced by the company has been referred to over the years as a “Confederate Perry” carbine, or a brass framed “Confederate Maynard”. From outward appearances the gun looks quite similar to the 1st Model Maynard carbine, with a very narrow, flat wood stock, small frame and a round barrel without a forend. The semi-serpentine lever that operates the action of the carbine, and doubles as its triggerguard, also has a distinctly “Maynard” like appearance. The operation of the gun is more akin that of the Perry carbine, as lowering the lever tilts the breechblock down in the rear, raising the front of the breechblock and exposing the chamber for loading. This is essentially the principle upon which the Hall rifles and carbines operated as well, which is also a bit of irony that will be touched upon below. This “tilting breech” mechanism was quite different from that of the Maynard, whose frame remained rigid and whose barrel tilted downward for loading when the lever was operated. The percussion ignition carbine had a round .54 caliber iron barrel and was rifled with seven grooves. The barrel was nominally 21 ½” measured to the front of the frame, and about 22 ½” when measured to the front of the breechblock. These “North Carolina” barrels are noted to have originated in Jamestown, NC, the heart of North Carolina gunmaking and the home of Confederate arms makers H.C. Lamb and Mendenhall, Jones & Gardner, two name just two. The iron breech block had a bronze ring at the front that was intended to provide a partial gas seal and to solve the problem that had plagued the Hall breechloading design; the leak of hot gasses into the face of the shooter! The frame was of bronze, although some sources call it brass. The official composition of the frames of the guns can be determined by an invoice from The Confederate States to Keen, Walker & Company, dated July 8, 1862 for “4,940 lbs of bronze - $1,976”. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc (usually about 60% copper to 40% zinc), while bronze is an alloy of copper and tin (usually about 85% copper to 15% tin) that can also contain other ingredients like aluminum, magnesium, arsenic, phosphorus and silicon. The bronze used in the Keen, Walker & Company carbine frames has the distinctive reddish tone of its high copper content, which is typical of the Confederate made alloy often termed “red brass” by collectors. Bronze is much harder and more corrosion resistant than brass, and has a higher melting point. As such it is much more suited to gunmaking than brass. Typically, Confederate made bronze varied in the percentage content of the various ingredients, so the color of two pieces alloyed in different batches and then used in the production of the same gun rarely match exactly. The guns had simple fixed rear sights and along brass blades dovetailed into the top of the barrel, near the muzzle. The barrels were either browned or blued, and guns with both types of finishes are present on the barrels of extant examples. The balance of the iron parts were reportedly case colored, although some may have been blued, or the case coloring may have been oil quenched, resulting in more muted, dusky bluish colors than are typically associated with that type of finish. The wooden buttstock had a simple iron buttplate, and was secured to the frame with two screws through the brass tang extension on top and two more screws through the iron extension on the bottom. Interestingly the screws were “common wood screws”, exactly the type that Major Downer of the Richmond Arsenal complained about when examined the muzzleloading carbines supplied by Bilharz, Hall & Company 20 miles north of Danville. A short sling bar was mounted on the left side of the frame from which a small iron sling ring was suspended. The guns were unmarked with the exception of a P proof that appears on most barrels, the same type of “P” that appears on the barrels of Bilharz, Hall & Company carbines. The only other marks are internal assembly marks, typically large, crude Roman numerals, and sometimes a small witness alignment mark at the barrel to frame joint. The first delivery of the Keen, Walker & Company Tilting Breech Carbines was on May 10 of 1862, when 101 of the guns were accepted at the Danville Arsenal and inspected by Lieutenant E.S. Hutter who approved them and the accompanying invoice for $5,050, a price of $50 per carbine. In mid June, the company advertised that it was looking to “employ 2o to 30 steady gunsmith hands”. It is not clear if they were for the production of additional carbines or for another project that they would be undertaking shortly. In either case, two more deliveries of the Tilting Breech carbines were made in September of 1862 at the lower rate of $40 per gun. The first delivery was on the 3rd for 100 guns (with the invoice paid on the 9th) and the second delivery was 81 guns on the 16th with the invoice paid on the 19th. No further deliveries of the carbines are noted, and based upon the original documents only 282 of the guns were delivered, all between May and September of 1862. The firm then applied all of their efforts to doing work for the other Confederate gunmaker in Danville, Read & Watson. Keen, Walker & Company would work to alter pre-war Hall rifles, made with a very similar tilting breech mechanism to their carbines, and convert them to muzzleloading rifles. This seems incredibly strange that a company would produce a sorely needed breechloading cavalry carbine would then concentrate its efforts on taking a breechloader and turning it into a much less useful muzzleloader. One of the last documents related to Keen, Walker & Company found in the Confederate Citizen Files is an invoice from the Confederate States to Keen, Walker & Co. dated April 18, 1863 for $177.90 for “five hundred ninety three pounds iron @ thirty cents per pound”. The invoice was paid on May 8, 1863, and the iron was likely used in the alteration of the Hall rifles that Keen, Walker & Company was doing on behalf of Reed & Watson. It appears that after the summer or fall of 1863 that Keen, Walker & Company ceased to exist, although William W. Keen would continue to do business with the Confederacy for the balance of the war, providing rental space to the quartermaster department and selling foodstuffs to them as well. Walker would be the last Confederate mayor of Danville, VA and would also serve as the first post-war mayor for the town, during the early days of reconstruction.

Offered here is a FINE condition example of a very scarce Keen, Walker & Company Tilting Breech Carbine. The gun appears to be 100% complete and correct in every way and has a wonderful look to it. The gun bears the assembly number XXV on the inner surfaces of both the iron and brass frame tangs and in the upper recess of the buttstock. The barrel is full length, measuring 22 ½” to the face of the breechblock and 21 5/8” to the frame juncture. The barrel is marked with the Danville style P on the right hand side, just forward of the frame juncture. The action of the carbine functions smoothly and correctly, with the lever tilting the breechblock upwards when it is lowered and closing it when the lever is closed. The hammer functions crisply and engages both the half and full cock notches firmly and responds to the pull of the trigger, as it should. The original and correct fixed rear sight is in place on the top of the barrel as well as the original dovetailed brass blade front sight. The original iron sling bar is in place on the left side of the frame, but the sling ring is missing. The barrel has a nice, unmolested patina that is a mixture of trace streaks of original brown finish, medium pewter patina and patches of darker oxidized age discoloration. As much as 10%-20% of the original brown may remain, but it is primarily in scattered patches and in the protected areas near the frame. The largest patches of oxidation are near the muzzle and while they have the appearance of crusty surface roughness and scale they are in fact relatively smooth. The barrel shows some lightly scattered pinpricking and scattered peppering along with flecked patches of surface discoloration from oxidation. The bore of the gun rates about GOOD+ overall, and retains strong rifling throughout. The bore shows significant oxidation and moderate pitting along its length, along with some patches of more serious erosion. The lever and lower tang have a deep, dusky bluish patina that is probably the remnants of the original faded finish, either dull blue, oil quenched case coloring or bluing. The iron breechblock appears to retain traces of brown on it, and the original bronze obturation ring is present at the front of the chamber. The hammer retains a dusky mix of bluish finish and brownish patina and has a small chip missing form the forward edge of its lip. The bronze frame has a wonderful, untouched deep ocher patina that shows on indication of having ever been cleaned. The circular side plate has a slightly more yellow tone than the rest of the frame, suggesting the alloy of that piece had a slightly lower copper content than that balance of the frame. As noted above, this is a typical feature of authentic Confederate made bronze/brass made firearms. The frame shows some minor scuffs and impact marks with the minor dents and mars that would be expected on a brass framed cavalry carbine. The buttstock is in about FINE condition and matches the appearance of the balance of the gun perfectly. While the frame to wood fit is not exact and perfect, the wood is clearly numbered to the gun and the slight gapping appears to be the result of “ordinary wood screws”, with their fine threads not appropriate to gun making, having worn in their holes and slightly loosened over time. As noted previously, this same complaint was made about the Bilharz guns as well, and the minor gapping and fit issues 150 years later are why Richmond wanted different screws to be used in the construction of these guns. The buttstock is carved with the period initials W H B on the obverse. It would be nice to try to identify the gun to “WHB” but that would be almost impossible to do accurately. The buttstock is solid and complete and free of any breaks, cracks or repairs. It does, however, show the usual bumps, dings minor rubs and mars typical of a century-and-a-half old military firearm that saw real service in the field.

Overall this is a really wonderful example of a very scarce Confederate made breechloading cavalry carbine. These small production run CS made carbines are always very desirable and rarely appear on the market for sale. With a production of only 282 of the guns, even if 10% survive today (which would be a very high survival rate for a Confederate made gun) that means only 28 of them are out there! Considering that the survival rate of numbered Confederate Enfield rifle muskets is only about 1%, it would be reasonable to assume that even if the average Confederate cavalryman had the forethought to think that this unique carbine was something special and worth preserving, it seems unlikely that more than 5% might exist today. These guns have a wonderful look to them with their brass frames and sleek styling and certainly stand out when hanging on the wall in a display of Confederate arms. If you have been looking to add a really wonderful example of a very scarce Confederate made carbine to your advance Civil War carbine collection, then this would be a great one to acquire. It is a gorgeous example of CS ingenuity and manufacturing capabilities, even when dealing with a lack of machinery and resources. This is a great Confederate made gun that you will extremely glad to add to your collection.

SOLD