Confederate J.P. Murray Type I Rifle #29

- Product Code: FLA-3296-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

The American South was woefully ill prepared and under equipped for the war that the seceding states found themselves party to in April of 1861. While southern propaganda abounded with enthusiasm of Confederate leaders like Robert Toombs, who is credited with the classic quote “we could beat those Yankees with corn stalks”, the reality was (as Toombs later admitted), “…they wouldn’t fight with corn stalks”. To that end, the agrarian south with minimal industry and manufacturing capability made a Herculean effort to place itself on a war footing and to arm the newly raised Confederate army. Across the southern states those men who had the vision, capability and financial resources embarked upon the production of small arms for the army. The pattern of rifle most favored and produced by numerous small shops throughout the south was the “Harper’s Ferry” pattern rifle, based upon the US Model 1841 “Mississippi” rifle. In many cases the gun was somewhat simplified, and the brass patchbox was eliminated, but the inspiration was still clear. As the war progressed, these rifles were often further simplified, and the double-strapped upper band was simplified to a single upper band and a nose cap, and much like the original evolution of the “Harper’s Ferry Rifle” from the Model 1841 to the Model 1855, the southern copies often started to resemble the latter arm. In nearly all cases, whether produced in Georgia, Tennessee, or North Carolina, the basic rifle remained the same; a single shot, muzzle loading, percussion ignition rifle with a nominally 33” round barrel, in either .54 or .58 caliber, typically brass mounted and usually with simple fixed sights. Details varied from maker to maker (and sometimes during the production run of a single maker), but the basic southern made military rifle was born during the latter part of 1861 and early 1862. One of the classic examples of such a southern made rifle are those known to collectors as the J.P. Murray rifle, a gun that is more accurately attributed to Greenwood & Gray of Columbus, GA.

The story of Greenwood & Gray has always been somewhat murky, and even the standard work on CS long arms, Confederate Rifles & Muskets by John D. Murphy M.D. and H. Michael Madaus provides minimal background on the firm. The company was a partnership between the brothers John D. & William C. Gray and Eldridge S. Greenwood. Murphy & Madaus concentrate on William Gray and Eldridge Greenwood, noting that “less is known about John D. Gray”. While William and Eldridge may have been the day-to-day operators of the production facility in Columbus, GA, it is quite clear from my additional research that the driving force, financial backing and political connections to establish and operate the arms manufactory were all directly attributable to John D. Gray. John D. Gray was born in London England in 1808 and emigrated to South Carolina with his parents as a child. In the 1820s he and his brother William established a successful construction business that proceeded to build roads within the state as well as several jails, courthouses and even a lunatic asylum. The company constructed the first rail line in South Carolina, and proceeded to build additional railroads in northern Florida. He and his brother then relocated to Georgia and continued to build railroads, including what would become the Macon & Western (which he also ran) and building the Western & Atlantic Railroad from Dalton, GA to Chattanooga, TN, as well as lines that ran to August, Savannah and Rome. His building efforts also took him into Alabama, where he built a rail line from Opelika, AL to Columbus, GA. Gray’s diverse businesses included everything from a steamboat line and a textile mill in South Carolina to furniture making factory and mining in the region around the town he founded in northern Georgia near the Tennessee line, appropriately named “Graysville”. His Chatata Lead Mine, located near Charleston, TN would become a vital resource for the Confederacy during the coming years. One of the business ventures in Columbus, GA was Greenwood & Gray, a rope manufactory that occupied the third floor of the Carter Mill building. Other tenants of the building during mid-1861 were A.D. DeWitt on the first floor, who briefly produced swords for the Confederacy, oil-cloth makers Brands & Korner on the second floor, and Haiman & Brother (another sword maker) on the fourth floor. DeWitt moved out of the building by the fall of 1861 as did the Haiman operation due to its expansion. Brands & Korner plied a lucrative trade with the Confederacy, primarily providing drums, drum heads, drum sticks, fifes and covers for canon rammers. It was in this building, where Greenwood & Gray were already operating (and with the additional space made available with departure of the two sword makers) that John D. Gray would establish his Columbus Armory. Gray was already doing substantial business with the Confederate government before he officially entered the arms making business. He was a large supplier of wooden items from his furniture factory (primarily buckets) as well as raw lumber. His lead mine was almost immediately working strictly for the Confederate Nitre & Mining Bureau, with thousands of pounds of lead being shipped to Richmond to be turned into bullets. It was with this already established relationship with the Confederate Ordnance Department and Quartermaster Bureau that Gray would write his well-documented letter to Confederate Chief of Ordnance Josiah Gorgas on May 26, 1862. The letter read in part:

“I have in operation a manufactory of small arms at Columbus in this State and am now turning out about six guns per day – after the Harpers Ferry or Mississippi rifle pattern and will have two hundred stand on hand in a few days.”

Gray went on to note that he was producing the arms without any contract but was hoping that one was forthcoming. A few days later, Gray wrote to Captain Richard Cuyler at the Macon Arsenal to request that those workers employed at his manufactories (both in Graysville and Columbus) be listed as exempt from conscription to the army. Part of his justification for the request was that he claimed to

“…have a contact with the Ordnance Department at Knoxville – approved by the department at Richmond, for making two hundred rifles and one thousand carbines. This contract is to be completed in eight or nine months.”

It is generally believed that the two hundred rifles that he claimed to have a contract for were the ones he had told Gorgas that he would soon “on hand”. The first documentable delivery of arms to Knoxville were 122 “Mississippi Rifles” in July of 1862 at $45 each, accepted by Lt. P.M. McClung of the Confederate Ordnance Department. His next delivery was on August 2, 1862 when he delivered 79 cavalry carbines at $43 each to Lt. McClung. His next delivery was on September 16, with 100 additional carbines at the same price. This time Captain S.H. Reynolds accepted the guns. Another 100 carbines were delivered to Capt. Reynolds on October 16, 1862 at the same price. The final delivery of arms to the Confederate central government that I can document occurred on November 12, 1862. This time it included 61 “Mississippi Rifles” and 69 cavalry carbines at $45 and $43 each, respectively. All totaled, it appears that Gray managed to deliver 183 “Mississippi Rifles” and 348 cavalry carbines to the Confederacy. It appears that all of Gray’s additional production would go to fill a contract with the State of Alabama. According to Quartermaster General of Alabama’s annual reports, Gray delivered 262 “Mississippi Rifles” and 73 cavalry carbines between October 1 of 1863 and November 1 of 1864. These rather paltry deliveries suggest that Gray’s claim to be able to produce “six guns per day” was optimistic at best, as nearly a year passed between his last delivery to Knoxville and his first deliveries to Alabama. Additionally, over a two-year period between that final Knoxville delivery and his last Alabama delivery he was only able to produce 335 arms, less than half a gun a day in a two-year period! Some insights into the issues that Gray was having might be provided by two letters that he penned to the Ordnance Department in Richmond. One, dated March 13, 1863 was a request for “drawings of small rifle hammers”, suggesting some sort of design issue with that component at his manufactory. The other, to Major W.S. Downer at Richmond was a request for help in obtaining 2,000 musket cones (nipples), as his supplier was not either not able to provide them or was doing it too slowly. The letter is difficult to read and it is not clear if Gray wanted Downer to provide the cones from Richmond or simply to apply pressure to his provider so that he would actually receive them. By May of 1863, the Columbus Armory was producing pick axes for the Confederate government, in addition to the firearms that he was producing for Alabama during the same period. Invoices for five such deliveries between May 13 and September 2, 1863 survive, indicating that Gray delivered some 1,672 picks during that five-month period; many more picks that guns! These were billed at $4.00 each, except for one delivery of 318 on July 28 that were only $3.80 each, although no reason is noted for the slightly lower price. A major misfortune befell Gray’s manufacturing efforts when Union troops destroyed his furniture manufactory in Graysville in November of 1863 as part of the fighting around Ringgold Gap. It is generally believed that this furniture factory was Gray’s source for rifle and carbine stocks. Local newspaper accounts suggest that by the end of 1863 the work at the manufactory had transitioned from a focus on arms production to tools and related items, including shovels, axes, chains, kettles, skillets and frying pans. His “help wanted” ads additionally indicate that he was looking for unskilled African-American laborers as well as skilled ones who could work as blacksmiths and carpenters. It is possible that in addition to losing his source of gunstocks that he may have lost many of his skilled white labor to the conscription that was becoming so important to keep men in the ranks of the Confederate army. Correspondence from other southern arms makers indicate that as the war progressed the loss of skilled labor was as great a difficulty to overcome as the lack of the necessary raw materials for firearms production. As Union cavalry swept through southern Georgia and Alabama in 1865, his Columbus manufactory was burned, and Gray was out of the manufacturing business completely, both firearms and all other items. In total, it appears that Gray’s Columbus Armory was only able to deliver 445 rifles and 421 carbines during its operations from mid-1861 to late 1864, suggesting that the average output was less than one gun per day during that period. After the war, Gray dedicated himself to rebuilding Graysville as well as much of the infrastructure that had been destroyed by the Union army in the Georgia, including bridges and railroads. Gray worked diligently at these projects until his death in Graysville on November 17, 1878.

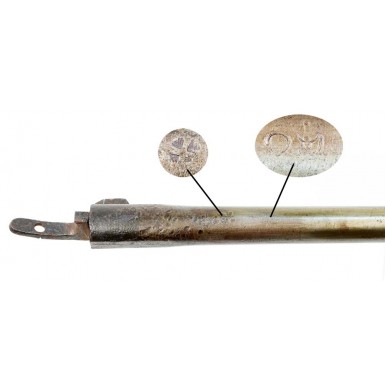

As indicated in his letter to Gorgas on May 26, 1862, the rifles that were produced by John D. Gray’s “Columbus Armory” at the Greenwood and Gray premises in Columbus, GA were of the “Harpers Ferry or Mississippi rifle pattern”. Technically two variants of the guns were produced with an early production “Type I” and a later production “Type II”. The “Type I” guns are more like the M-1841 Mississippi Rifle with a double strapped upper barrel band, a lower band with an extension on its lower leading edge, and a flat, S-shaped side plate. The later Type II guns are more like a M-1855 rifle, with a brass nose cap, and flat bands with the upper band not double strapped nor with a projection on the lower band. Instead of the S-shaped side plate, recessed brass washers are used to prevent the over tightening of the lock mounting bolts, “side nail cups” as the English called them. As with most Confederate arms, “transitional” models exist that shows both “early” and “late” features on the same gun. To add slightly to the confusion, Murphy & Madaus apply the designation of “Type III” to the “Type II” guns that are Alabama contract marked, but from a functional perspective, only two types of rifles were manufactured. Other than the differences noted above, both patterns were essentially the same, with an overall length of approximately 49” and a nominally 33” barrel, although minor variations in length are not uncommon. The guns are .58 caliber and rifled with three grooves and are brass mounted. Sights are typical of the M-1841 rifle with a fixed rear sight dovetailed into the barrel forward of the breech and a small brass blade near the muzzle. Mountings are of brass with a two-piece triggerguard, an iron (or occasionally brass) trigger, and a pair of iron loop sling swivels mounted on the triggerguard bow and the upper barrel band. The buttplate is brass with a flat, “shotgun” profile and there is no patchbox in the stock, a feature often omitted on Confederate produced “Mississippi” rifles. It appears that Boyle & Gamble produced muzzle-ring bayonet adapters (to accept Boyle & Gamble saber bayonets) were mounted on many of the guns produced for delivery to the Confederate central government, and that most of the guns delivered to the state of Alabama do not have that feature. Markings are somewhat sparse on the guns. The locks on most examples are stamped in two lines, forward of the hammer, J.P. MURRAY over COLUMBUS, GA. This marking has led to these arms being known as “JP Murray” rifles, when they are really the work of John D. Gray’s Columbus Armory located at the Greenwood & Gray premises. The mark is that of John P. Murray, a gunsmith who had been working in Columbus, GA prior to the outbreak of the war. Murray’s story is somewhat interesting in that, like the Gray brothers, he hailed from South Carolina. Murray had been in a gunmaking partnership in Charleston with Benjamin G. Happoldt. The firm of Happoldt & Murray operated in Charleston from about 1856 until the partners relocated to Columbus, circa 1859-1860. Benjamin was the brother of John H. Happoldt, another Charleston, SC gunsmith who would alter numerous US M-1841 Mississippi Rifles to accept saber bayonets for the Confederacy during the early months of the war. When Gray established his rifle works, he hired Murray as his foreman and master armorer. The stamp used on the Gray’s Columbus Armory manufactured rifle and carbine locks is the same one Murray had used in his civilian gunmaking business, and a handful of civilian rifles are known with this mark as well. At least one carbine is known with a COLUMBUS ARMORY marked lock, suggesting that towards the end of production a new stamp was finally procured. The other markings and features on that gun are like those associated with the other known “Greenwood & Gray” / “JP Murray” arms, indicating that they came from the same shop. Most examples of Gray’s rifles and carbines are stamped with two inspection marks on the upper left breech, the letters PRO for “proved” and the letters FCH for Captain (eventually Major) F.C. Humphries of the Columbus Arsenal, who inspected most of the arms produced in Gray’s facility. The bottoms of many of the barrels also bear the “Maltese Cross” or “windmill” inspection mark of Nathan D. Cross, a Selma Arsenal inspector who inspected many of the Columbus made barrels. The only other markings typically associated with the guns are the letters ALA and a date (usually 1864) on the Alabama contract guns, which are usually stamped on the barrel above the other inspection marks. Also, the tops of the barrels of most of the guns produced with Boyle & Gamble bayonet adapter rings appear to have been stamped with the number of the ring and bayonet to mate these parts. Internally, the lock, hammer neck and sometimes the bottom of the barrel are stamped with assembly numbers that some consider to be serial numbers as well. In some cases, the lock screw heads are numbered as well, as on the Columbus Armory marked carbine and at least two Type II rifles. From examination of several extant examples it appears the numbers are only batch or assembly numbers as very low numbered examples of “Type II” guns (including single digits) are known, and it seems almost definite that these guns were produced later than the “Type I” examples.

Offered here is a GOOD+ condition (for a Confederate gun, more like “very good”) example of what I feel is a particularly early production Type I Columbus Armory Rifle by Greenwood & Gray (aka “JP Murray”). The rifle is assembly numbered 29 and this mark is found inside the lock plate, forward and above the mainspring, on the inner neck of the hammer and on the bottom of the barrel. The bottom of the barrel also bears the Nathaniel D. Cross “windmill” inspection mark. There is no visible PRO or FCH on the breech, but these may have been obliterated by pitting, or the gun may be so early that these inspection marks were not applied. Additionally, no number is present on the top of the barrel near the muzzle, and there is no indication that a muzzle ring bayonet adapter was ever installed on the gun, but again age and wear may have obliterated the mark or any signs of bayonet adapter use. The only other assembly or manufacturing marks are an X assembly mark cut in the triggerguard tang mortise of the stock and a matching mark on the interior of the triggerguard tang. The reverse of the buttstock is carved with a series of letters and Roman numerals, but they are difficult to decipher. They appear to be a capital V followed by a Pwith some smaller letters between them, followed by I X I, with the “I” marks having cross hatch decorations in their centers. This rifle could well be marked by the solider who carried it, but the markings are so cryptic I can’t begin to determine what they mean. The rifle measures 48 ¾” in overall length, with a 33” round barrel. A small brass blade front sight is positioned ¾” from the muzzle and dovetailed rear sight is located 2 ¾” from the breech. The rifle has been “smooth-bored”, probably for post-war use as a shotgun, and is now approximately .64 caliber with no rifling present. The fixed rear sight appears to be a period of use replacement, and is located in the original dovetail notch. The sight shows the same age, wear and patina as the balance of the gun. What appears to be the original ramrod is present in the channel under the barrel. The rod is of iron, with a tapered trumpet head and with threads to accept cleaning implements at the opposite end. The rod appears to be full-length and unaltered. The two original iron loop sling swivels are present, with the upper mounted on the upper barrel band and the lower mounted on the front of the triggerguard bow. Both are slightly thicker and lower quality than those found on US made Mississippi Rifles, and the rivets are slightly cruder than on their US counterparts. The brass furniture shows rough hand finishing and the interior surfaces of the buttplate and barrel bands show the somewhat crude casting and tool marks often associated with southern made arms. Likewise, the stock shows the rough work of semi-trained workmen, particularly on the interior where tool marks are obvious in the lock mortise and barrel channel.

As noted earlier, the rifle is in about GOOD+ condition, and for a Confederate gun it is really about “very good”. The gun shows light to moderate pitting over most of the iron surfaces, with the breech of the barrel showing moderate to heavy pitting, which becomes less severe forward of the breech, and beyond the rear sight towards the muzzle. In some areas, the pitting is only pinpricking or fairly light, but in others it is more moderate. The barrel has a mottle grayish-brown patina, suggesting the barrel may have been cleaned long ago, and is toning down with age. The breech shows a somewhat thicker brown patina, with the barrel having a more mottled appearance forward of the rear sight. The breech plug was muscled out of the gun at some point in time, damaging the tang. This is not uncommon for arms that saw post-Civil War civilian use, as many Confederate made guns did, often for decades after the war. The tang was repaired, but still shows a crack on one side of the screw hole, and is slightly misshapen. However, the breech plug and tang both appear to be original to the rifle. As noted the rear sight is an old, probably period of use replacement. The lock has a mottled oxidized gray patina similar to the barrel, but shows only lightly scattered pitting. The J.P. MURRAY / COLUMBUS, GA mark remains crisp and clear on the lock the plate and is one of the better marked plates that I have seen. The interior of the lock is very well made, with the interior of the plate showing traces of its original case hardening and some of the small parts retaining traces of their fired blued finish. Clearly Murray was a skilled gunmaker, who concentrated his efforts on the most important parts of the gun, like the lock, leaving the semi-skilled workers to produce the stocks and furniture. The lock is functionally excellent and operates crisply and correctly on all positions. One of the lock mounting screws may be an old, period of use replacement. As noted the bore of the rifle is now .64 caliber and has been smoothed. It remains in good condition with some lightly scattered pitting and oxidation along its length. The brass furniture has a lovely, untouched umber patina and shows a slightly reddish hue, typical of the copper rich brass (aka “red brass”) often found in Confederate made belt plates and gun furniture. The stock is in about GOOD+ to NEAR VERY GOOD condition, and although crude on the interior shows workman like fitting and finishing on the exterior. The stock is solid and full-length and free of any breaks or repairs. There are some minor cracks and some minor wood loss as well, all from service and use. There is some minor splintered loss on the obverse at the forend tip, most of which is concealed by the upper barrel band, as well as a couple of small splinters missing from the ramrod channel. There is also some loss from burn out behind the bolster, and some minor chipping around the breech plug tang. The stock appears to have been lightly sanded at some point in time, but the contours around the lock mortise and stock flat still have good definition and the lines and edges only show minor rounding. Amazingly, the stock remains solid and stable with no major condition issues other than the wear associated with Confederate Civil War use and post-war carry to help keep food on the table.

Overall this is a very nice, complete and correct example of an extremely scarce Columbus Armory J.P. Murry Type I Rifle. The only parts that do not appear to be absolutely original to Greenwood & Gray’s manufacture of the gun are the rear sight and one of the lock mounting screws. In all other respects this rifle appears to be 100% correct and of Confederate manufacture. These very scarce rifles usually show hard use when they are encountered today, and this one is not exception, as the burn out at the bolster and pitting in that area suggest it was fired hundreds, if not thousands of times; initially at Yankees, but later likely at food and various four-legged pests. For a number of reasons described above, I feel that this is a very early production rifle and likely one of the first 122 rifles delivered to Lt. McClung in Knoxville in July of 1862. This long Confederate service life, which started a year before the battle of Gettysburg, is no doubt the reason the rifle shows so many of the marks and mars from service. For advanced collectors of Civil War weapons, the pinnacle has always been Confederate made firearms. Their low production figures and even lower survival rate make them elusive prey for Confederate arms collector. This rifle remains in wonderful, if well used, original condition and is free of the numerous repairs and restorations that plague most Confederate made arms on the market today. For any advanced collector of Civil War long arms, this is a rifle that you will certainly be proud to own and will certainly enjoying displaying for many years to come, as you will never have to make any apologies for it. With only 445 “J.P. Murray” rifles produced, and with no more than about 180 or so being of the “Type I” configuration, these rifles rarely appear on the market for sale. Don’t miss your chance to own a wonderful piece of Confederate Civil War history.

SOLD