Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire Army Revolver

- Product Code: FHG-1840-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

The firm of Allen & Wheelock was a true powerhouse of American arms manufacturing during the middle of the 19th century. Unlike the major American arms producers of the era like Colt and Remington, Allen & Wheelock concentrated upon manufacturing arms for civilian sale rather than focusing on trying to obtain government military contracts, although some products were designed with that goal in mind. The company was founded in 1831 when Ethan Allen started to make cutlery in Milford, MA. Allen specialized in making the knives and tools needed for cobblers. Allen then moved his small facility to North Grafton, MA where he added a cane gun to his line of shoemaker’s tools. In 1836 Allen introduced his “Pocket Rifle”, a single action, under hammer, long-barreled rifled pistol in .31 caliber. With the initial success of this product, Allen pursued the design and patent of a double action pocket pistol, and eventually the pepperboxes that would be the mainstay of his firearms product line for the next 20 years. In 1837 he brought his brother-in-law Charles Thurber into the business, creating Allen & Thurber, and in 1842 the company moved to Norwich, CT, where it would remain until 1847. In 1847, the firm moved to Worcester, MA, where it would remain until it went out of business in 1871. In 1854 Thomas Wheelock, another of Allen’s brother’s-in-law joined the company, and it was rebranded as Allen, Thurber & Company. In 1856 Charles Thurber retired, and the company known as Allen & Wheelock came into existence. In 1865, after Wheelock’s death the previous year, the company was renamed for the last time E. Allen & Company. The new company included more of Allen’s extended family, his son’s-in-law Sullivan Forehand and Henry Wadsworth. After Allen’s death in 1871, the 34-year-old company would change names again, this time to Forehand & Wadsworth, and the Allen name would be left to history. During that 34-year history, the company produced thousands of firearms ranging from single shot percussion pocket pistols and multi-barrel percussion pepperboxes, to rather innovative and complicated large frame percussion revolvers and even some of the first truly successful cartridge revolvers. The development of Allen’s “Lip Fire” self-contained cartridges were truly revolutionary, especially because the rimfire cartridges of the era that were offered by Smith & Wesson in their #1 and #2 revolvers were only .22 and .32 caliber respectively, while Allen offered self-contained handgun cartridges in the much larger calibers of .36 and .44. Unfortunately, the production of Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire and Rim Fire series of revolvers was brought to a screeching halt due to litigation from Smith & Wesson, who were defending the bored through cylinder patent of Rollin White, which they had purchased exclusive access to. Allen managed to produce his sidehammer rimfire revolvers for slightly more than 3 years, from about 1859 until November of 1863, before the patent infringement suit shut down the production of that product line as well. His revolutionary Lip Fire revolvers saw a much shorter production life, with the guns being introduced in late 1860 or early 1861 and being put out of production by the November 1863 court order. Despite these setbacks, Allen persevered, continuing to manufacture percussion revolvers, and long arms, including a drop-breech cartridge rifle and double-barreled shotguns with metal wrists. Allen also produced a successful line of single shot, cartridge derringers that did not infringe upon the Rollin White patent. Allen’s innovations in revolver actions, and self-contained cartridge designs earned him numerous patents. His use of large-scale production techniques and interchangeable parts also made him a leader within his industry. While certainly not as famous as Samuel Colt, Eliphalet Remington or Oliver Winchester, the contributions of Ethan Allen to the American firearms industry were important and long lasting, and his high quality arms offer a worthy and wide array of collecting possibilities.

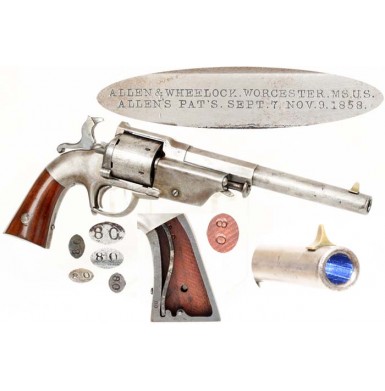

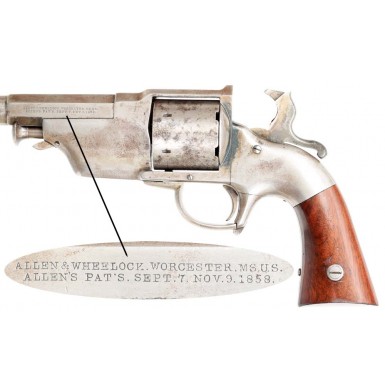

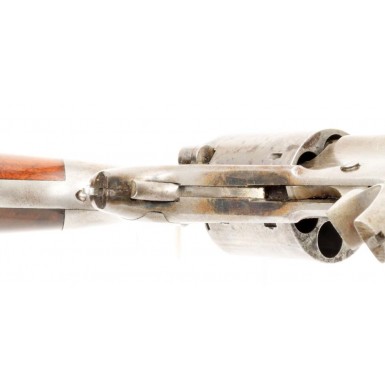

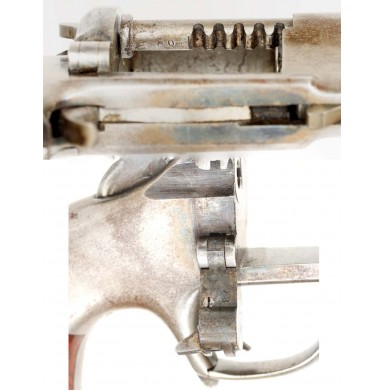

The Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire revolvers were more innovative in terms of their ammunition than from a mechanical or functional standpoint. The Smith & Wesson rimfire ammunition was produced with expensive priming compound distributed through the entire rim of the cartridge, as there was no way to know where the hammer would fall on the rim and cause the ignition. The Allen concept changed the conventional circular cartridge rim to a small “lip”, about 1/8 of the diameter of the cartridge casing, and this lip engaged a slot machined into the rear of the revolver cylinder. This meant that hammer would hit a specific part of the case rim, and the priming compound only had to be in that location, not throughout the rim of the case. The resultant savings in the the amount of primer compound needed was tremendous, and this saved money. As Allen had patented his unique ammunition, he became the only source for it, and thus controlled the market, both a good and a bad thing as it turned out. Foreseeing the coming Civil War, Allen realized that a cartridge revolver, chambered for a “military sized” round, would be very enticing to the US military, and he concentrated his efforts towards the production of a .44 caliber “Army” and a .36 caliber “Navy” model. Unfortunately, the US military was hesitant to acquire arms that required “patent” ammunition, as this meant the military was dependent upon the manufacturer to keep a sufficient supply of the ammunition available and was at the mercy of the supplier in terms of the ammunition cost. The US military hierarchy preferred to acquire percussion revolvers that could be supplied with conventional paper cartridges produced in US Ordnance Department arsenals and by contractors without the restrictions of “patent” ammunition. As such, Allen’s Lip Fire revolvers were only purchased privately by some officers and men on a fairly small scale, while the US military did acquire some of his large frame percussion revolvers for general issue. The Lip Fire revolvers appear to have been developed concurrently with with Allen’s large bore percussion center hammer models, which were quite similar in appearance and operation, with the exception of the parts that were specific to either percussion or cartridge operation. The Allen & Wheelock Center Hammer Lip Fire “Army” revolver was the large bore, .44 caliber revolver in the series. Like all of the Allen “Center Hammer” revolvers, it used a single-action mechanism but fired Allen’s proprietary, self-contained .44 Lip Fire cartridge. It is estimated that between 250 and 500 of these revolvers were produced from about mid-1860 until November of 1863, when a court order ended production of Allen revolvers with bored through cylinders. As a result of the relatively small production numbers, this scarce revolver is often missing from even advanced collections of Civil War era secondary martial revolvers. The Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire Army revolver had a six shot cylinder and a 7 ““ half-octagon/half-round barrel. They guns were produced with two different styles of loading gate, with the earliest production guns having a gate hinged at the top and the later production guns having one hinged at the bottom. The guns were also produced with two different styles of grips, one being a standard taper (the most commonly encountered version) and the other having a pronounced “flare” towards their bottoms. The guns used a unique cam-action trigger guard to actuate the ejector, which removed the spent cases from the cylinder. This same mechanism provide the loading lever action for the percussion version of the Center Hammer Army revolver. The revolvers were blued, with color case hardened hammers and triggerguards, and the two-piece walnut grips were varnished. The guns were “serial numbered” (really batch or assembly numbered) on most of the major components, including the frame (under the grips), on the face of the cylinder, on the cylinder arbor pin, on the ejector rod, inside the grips and on many of the internal parts. The only other markings usually found on the Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire Army revolver was the two-line address and patent date mark found the left side of octagon portion of the barrel. The most commonly encountered marking read:

ALLEN & WHEELOCK, WORCESTER, MS. US

ALLEN’s PAT’s SEPT. 7, NOV 9, 1858.

Offered here is a NEAR FINE condition example of an Allen & Wheelock Center Hammer Lip Fire Army Revolver. The gun is 100% complete, correct and original and unlike most Lip Fire revolvers encountered today, it remains in its original unaltered, Lip Fire configuration. While it made sense from a business standpoint for Allen to monopolize the manufacture of the special Lip Fire ammunition required for the revolvers, it also meant that ammunition could easily become scarce, especially on the western frontier during the latter part of the 1860s and during 1870s. As a result, most Allen Lip Fire Army revolvers encountered today have had their cylinders modified to accept more readily available .44 Rimfire ammunition. This gun has not had the cylinder so altered. The gun is one of the later production Lip Fire “Army” revolvers, with a loading gate that is hinged on the bottom, rather than the top. This was an improvement over the weaker and less ergonomic top-hinged gate that was initially used on the guns. The other improvement incorporated on these 2nd model revolvers was the addition of a pin cast into the right side of the frame upon which the hammer rotated. The first pattern revolvers had the side plate screw enter from the right side of the frame and double as the hammer screw, but this system proved to put too much tension on the screw. The improved system allowed the screw to enter through the side plate on the left side of the frame and engage threads on the new hammer stud. The revolver also has the most commonly encountered standard profile grips with a normal taper and no flare at the bottom. The revolver is clearly and crisply marked ALLEN & WHEELOCK, WORCESTER, MS. US / ALLEN’s PAT’s SEPT. 7, NOV 9, 1858 on the left side of the octagon portion of the barrel. These marks are often weak or poorly applied and it is nice to see such a crisp, clear marking. The serial (or assembly) number 80 is located on the lower left grip frame (concealed by the grips), on the face of cylinder, inside the loading gate, on the ejector rod, on the cylinder arbor pin and on the inside of both walnut grip panels. As noted the gun is in NEAR FINE and remains extremely crisp throughout. The frame has a smooth gray-brown patina with some strong traces of the original blued finish in the protected recesses around the recoil shield and under the hammer at the rear of the frame. Allen’s bluing was very fragile and the finish tended to flake off quite easily, making any Allen & Wheelock revolver with even traces of original finish a real find for collectors today. The barrel has a similar patina, with some minute traces of finish in the recess where the ejector rod housing and the barrel meet and on the face of the barrel web where the cylinder arbor pin enters the frame. The frame is completely smooth with no pitting and only a couple of very minute areas of the most minor pinpricking and some small flecks of minor surface oxidation, forward of the cylinder mouths. The barrel shows slightly more lightly scattered pinpricking, with some scattered flecks of minor surface oxidation and some scattered darker discoloration to the metal from age. The cylinder has a medium pewter gray patina that matches the balance of the revolver well, with a flecked “salt & pepper” pattern of minor surface discoloration evenly distributed over its external surfaces, and some small patches of minor surface oxidation on its the front and rear faces. The hammer retains about 30%+ of its original case coloring, which has faded and mixed with a silvery-gray patina and some light surface oxidation. The bore is in about VERY FINE condition, and remains mostly bright and shiny with crisp rifling its entire length. Only some lightly scattered pinpricking is present, scattered along the length of the bore. The revolver is mechanically EXCELLENT and still functions as crisply as the day it was made. The revolver, times, indexes, locks up and operates exactly as it should. The bottom-hinged loading gate still locks crisply into the closed position, and operates correctly as well. The triggerguard actuated ejector system works exactly as designed and still operates smoothly. The original brass blade front sight remains in place on the top of the barrel, near the muzzle, and has an attractive, untouched mustard patina and traces of verdigris around its base. The two-piece walnut grips are in about NEAR EXCELLENT condition and are free of any breaks, cracks or repairs. The grips retain about 90%+ of their original varnish, with only some light wear and finish loss along the high edges and contact points. The grips remain very crisp and sharp, but do show some minor bumps, dings and handling marks, appropriate to the age of the revolver.

Overall this is a really fine looking example of a relatively rare Civil War era revolver. When these guns are encountered they are typically found converted to rimfire and not in their original lip fire configuration. This lovely pistol is unaltered and in the original lip fire chambering and has not been messed with or molested in any way. These revolvers are only occasionally found offered for sale, and due to their relatively small production numbers even many advanced Civil War era pistol collections do not have one of these revolvers. This gun displays very well, retains some strong traces of the original finish, has not been altered to rimfire, and is 100% original, complete and correct. If you have been waiting to get a really crisp Allen & Wheelock Lip Fire Army with some original finish on it, here is your chance to own a really nice revolver that would be difficult to upgrade without spending a lot more money.

SOLD