Fine US Artillery Alteration of a Single Action Army Revolver

- Product Code: FHG-3521-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$5,995.00

In 1893 the United States military began the process of recalling the Colt Model 1873 Single Action Army .45 caliber revolvers, many of which had been in service for almost two decades, in order to replace them with the newly adopted Model 1892 Colt New Army Double Action .38 caliber revolver. Initially the new .38 revolvers were only issued to cavalry regiments, and as sufficient quantities were available to reequip an entire regiment, the new guns were issued, and the venerable .45 caliber single action Colts were returned to the nearest arsenal for storage and future issue if needed. However, the .45 caliber Colts still remained the standard service revolver for the infantry and artillery, with the new .38s being specifically intended for cavalry issue first and other branches as the new guns became available. It was during this time that complaints from the field continued to come from light artillery regiments about the length of the single action Colt’s barrel. The light or “horse” artillery had long complained that the barrel and holster length were uncomfortable for the men who were intended to ride upon the caissons and limbers of the artillery pieces while they were being drawn by the team of horses.

As a result of these complaints, in August of 1894, the Ordnance Department requested a study be completed at the National Armory in Springfield, MA regarding the feasibility of shortening the 7 ½” long barrels of the current stocks of .45 caliber revolvers to a more convenient length of between 5” and 5 ½”. Two sample guns were altered, one shortened to 5 ½” and one to 5”. The comparative tests between a standard 7 ½” barreled revolver, a 5 ½” barreled revolver and a 5” barreled revolver showed that the accuracy, penetration, velocities, and force of impact were not sufficiently altered to make a major difference in performance. While the tests noted the velocity of the bullet dropped in the shorter barrels, it was in fact no less than the velocity of the newly adopted .38 revolver round fired from the Model 1892’s 6” barrel, and in fact, even from the shorter barrels the .45 caliber round retained more impact energy than the new .38 Colt did. The initial test results were positive enough that in September additional tests were commenced, with alterations performed to six additional single action revolvers.

These guns were all late production Rinaldo A. Carr inspected guns in the 13XXXX serial number range, that had been delivered in 1890 and 1891 and were still in new, unissued condition. The guns had their barrels shortened a number of times, with the front sight relocated each time. The guns were tested for accuracy, penetration, velocities, and force of impact at each barrel length and the results were recorded. The initial testing took place with the factory original 7 ½” barrel length, and then each revolver had its barrel shortened to 6 ½”, 6”, 5 ½”, 5”, 4 ½” and 4”, with the same tests repeated at each length. The lengthy report regarding these tests is best summarized by a single sentence which reads:

“From the results of the test, the Board is of the opinion that the barrel of the service Cal. 45 Colt’s revolver might be reduced to the length of 4 ½” with no material loss in accuracy or in stopping power and with a slight gain in lightness and a decided gain in the ease of manipulation.”

The report was approved and endorsed at the highest levels of the Ordnance Department, with the additional note that, “The conclusions drawn from the tests, disregarding the “gain in ease of manipulation”, is that a length of barrel of 5 inches is the most advantageous.”

The final result was that on May 25 of 1895 an official order was forwarded to the Springfield Arsenal for the alteration of 250 “Colt’s Revolvers, Cal. 45” to have their barrels shortened to 5 ½”. Why the length of 5 ½” was chosen after 5” was recommended is unclear, but two factors probably influenced the decision. One reason was that the 5 ½” barrel was a standard production factory barrel length for civilian market Colt Single Action Army revolvers. The other may simply have been one of consistency, as a 5 ½” Model 1873 and a 6” Model 1892 revolver are very similar in overall length. These newly shortened revolvers were to be issued for field trials to various light artillery batteries.

At that time, the Colt Single Action Army “Artillery” alteration, as it is known by collectors, was officially born. Although the Ordnance Department never used the term “artillery” to describe the shortened .45 Colts, the fact that the shortening was prompted by complaints from the light artillery, and that the first 250 altered guns were issued to 10 light artillery batteries for field trials, 25 guns to each battery, have combined to give this pattern of martial Colt single action the nickname that it will have in collector parlance forever.

The Colt Single Action Army “Artillery” alteration is found in three primary variants with a fourth “odd ball” variation. These are categorized by noted Colt Single Action Army researcher, historian, collector, and author John Kopec as:

Type I: 5 ½” barrels with all (or mostly) mixed numbers on the parts.

Type II: 5 ½” barrels with all matching numbers except for the barrel.

Type III: 5 ½” barrels with all matching numbers.

Type IV: 7 ½” Barrels with mismatched numbers.

The Type I variation is the most commonly encountered “artillery” variant and will be discussed in greater detail below. The other variations are less often encountered and are explained once an understanding of the alteration process is arrived at.

The initial alterations of existing revolvers were performed at the Springfield Arsenal on guns that were still new in their packing crates and had not previously been issued. These guns required no repairs, maintenance, or refinishing. The only work required was the removal of the barrels, cutting them to 5 ½” and replacing the front sight in its new location. It is generally believed that the very first guns were so altered, and great care was taken to replace the altered barrels on the guns they had originally come from, resulting in the scarce “Type III” alterations that have all matching serial numbers. At some point in time, it was probably realized that there was no advantage to taking the time and effort to match the altered barrels to their original frames, and by eliminating this step the alteration process was speeded up at least a small amount, with the barrels now being randomly installed on whatever revolver was handy. This accounts for the relatively rare “Type II” alterations that have all matching numbers with the exception of the barrel. Once the supply of new, unissued revolvers was exhausted the process of altering used revolvers returned from the field began. In this case many of the guns had been in service on the frontier for more than a decade and in some cases closer to two decades. This meant that the guns required substantial work to put them back into serviceable condition. The guns were dissembled, cleaned, worn parts were replaced, barrels were altered to 5 ½” and then reassembled without regard to serial numbers, resulting in the most common of the “Artillery Alterations”, the “Type I”. The “Type IV” alteration is explained by the fact that after many of these guns were allocated to be sold as surplus, original, uncut 7 ½” barrels were sometimes reinstalled in them or, made available to the retailers like Francis Bannerman & Company, to make the guns more attractive to the buyers of these used handguns. While this variant is a real, period configuration for the revolvers, it is generally believed that the mixed number guns with 7 ½” barrels never saw military service in that configuration.

During the fiscal years of 1894-95 a total of 254 .45 caliber Colt revolvers were altered at Springfield Arsenal. These guns were in new condition and were not refinished. The following fiscal year, 1895-96 1,177 revolvers were refurbished by Colt, with barrels altered to 5 ½”, and the guns refinished. An additional 800 guns were repaired and refinished by Colt this same year but were not shortened to 5 ½”. Parts were replaced as needed for all of these revolvers as well. At this point it was generally felt that sufficient quantities of serviceable 5 ½” barreled guns were on hand, and no further work was performed for the next two years.

On 15 February 1898, the battleship USS Maine was sunk in Havana harbor and immediately the United States was on a war footing. A March 7, 1898, inventory of available small arms that could be “cleaned & repaired” and put into service at the Springfield Arsenal included “16,000 Calibre .45 revolvers”, along with some 24,000 Trapdoor rifles and 19,500 carbines. When the arsenal was queried about their ability to refurbish the arms without affecting the manufacture of the new “Magazine Rifle Caliber .30” (the Krag), they noted that in a normal 8-hour day the arsenal could clean and repair 180 rifles and carbines and 500 revolvers. The letters note that in the case of the revolvers, the cleaning and repairing would include “cutting off the barrels”. No mention is made of refinishing any of the arms, and with the repair rate of 500 per day, there is no practical way to assume the guns would be refinished. The estimated cost to affect these repairs and alterations to the Colt revolvers was $1.00 per gun. It is interesting to note that when the Springfield Armory was queried in 1895 about the cost of alteration, rebuilding and refinishing of the Colt revolvers being returned from the field, the arsenal contended that they were not able to make the reconditioned guns look like they did when “originally sent out”, but that they could perform the work for $2.00 per gun, applying a nitre blued finish. For $2.12 per gun the revolvers could be browned rather than blued. The 1895 quote from Colt to clean, repair and reblue the revolvers was $2.40 per gun, and an additional fee of $0.25 per gun would be applied for cutting off the barrels. In neither case did Springfield or Colt allow for the replacement of significantly worn parts in these quotes, which would result in a higher individual per gun cost as loading gates, hammers, ejectors, grips and even barrels, frames, and cylinders (as well as any other parts) needed to be replaced. With these prices in mind, it is clear that at $1.00 per gun, Springfield was simply cutting of the barrels, replacing the front sights, and doing the absolute minimum amount of work to get the stock of old revolvers into serviceable condition for issue. The alteration and repair of the revolvers commenced almost immediately and if the Springfield estimate was accurate, only about 33 workdays would be necessary to perform the job. This was timely as the United States declared war on Spain on 19 April 1898 and immediately started moving men and material to Cuba. It was the shortest declared war in US history, as it was over on August 12 of the same year. In total, Springfield would alter and refurbish some 16,317 .45 Colt revolvers in 1898. These altered guns were largely issued during the Spanish American War, with the most famous of these “artillery” revolvers being issued to Teddy Roosevelt’s 1st US Volunteer Cavalry, the famed “Rough Riders”.

Following the conclusion of the Spanish American War, many of the Colt revolvers remained in field service, particularly in the Philippines, where they saw hard use in the harsh tropical environment during the Philippine Insurrection of 1899-1902. As these altered Colts were returned from the field, in various states of wear, a process of repairing, refurbishing, and refinishing the guns began. A total of 5,294 .45 caliber Colt revolvers were reconditioned by the Colt factory between 1900 and 1903. Records indicate that some of the guns reworked during this time were sent in twice, suggesting that some of the guns repaired and refinished in 1900 or 1901 may have been returned to service in the Philippines and needed additional work a year or so later. Most of these guns had been previously altered to the 5 ½” barrel configuration by the Springfield Arsenal, but at least 72 did have their barrels shortened during their time at Colt. These guns received new replacement parts as needed, but these replacement parts were not serial numbered. This is logical, as the large majority of the guns were probably already mixed numbers, and it would serve no purpose to add a serial number to a barrel or cylinder that was being placed in a mismatched gun. These guns received a Colt refinish, usually the “government finish” of a color case hardened frame with the balance of the gun blued, although a few blued frame examples are known. The guns also received new grips that were marked with the inspection cartouche of Rinaldo A Carr, as well as the year of inspection once the guns were completed.

Springfield Armory also preformed some refurbishing of .45 Colts during this period, with 6 cleaned and repaired in 1900, 243 in 1901, 11 in 1902 and 61 altered and repaired in 1904. According to records, these guns were not refinished, but replacement parts were added as needed.

From the beginning of the process of altering and refurbishing Colt revolvers in 1894 through the end of their service life circa 1911, some of the guns were re-worked on as many as three or four times. Many went through at least two different alteration and reconditioning procedures, as nearly all of the guns refurbished by Colt during the 1900-1903 era had been previously altered at Springfield in 1898. As a result, significant variations can be observed in extant examples that do not appear to be “textbook”, but upon closer study appear to be absolutely correct, just uncommon. The constant replacement of worn parts (especially grips) at the national, state, and even regimental armorers’ level can result in a dazzling array of marking combinations that at first appear bizarre but are actually quite correct. During the nearly four-decade service life of the Colt Single Action Revolver thousands of spare parts were procured by the Ordnance Department to allow guns to remain in service in the field. This is why a 100% original and unaltered 7 ½” Colt “Cavalry” revolver is so prized by collectors. The great majority of 7 ½” guns were recalled, altered, and refurbished at the end of their initial service life and then served for another decade or more with shortened barrels and mixed serial numbers. In fact, the majority of guns that escaped this fate were either issued to state militias who did not turn them in in 1893-94, or were lost, stolen, or captured in the field during the Indian Wars. In the greater scheme of things nearly all of the real “Indian War” single actions were eventually altered, so the only reasonable way to get a real old west combat single action is to acquire an “Artillery” revolver with early production parts that were probably there for the days of intense conflict on the frontier from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s.

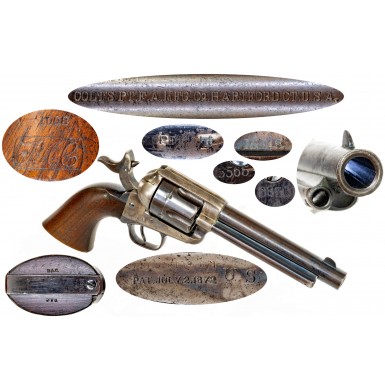

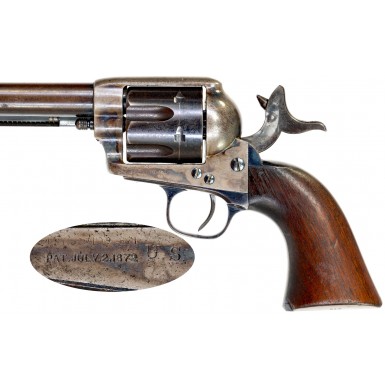

Offered here is a FINE example of a Colt Single Action Army “Artillery” Alteration Revolver. Like the large majority of the “Artillery” revolvers found today, it is a mixed numbers gun. The gun has a number of desirable and interesting features that will be discussed as the serial numbers and markings are addressed below, as many of the parts are from the early production period at the height of the Indian Wars. As with almost all Artillery models that underwent refinishing at least once during their service life, the markings are sometimes weak and difficult to read due to the buffing and necessary preparation of the metal for refinishing. The frame of the gun is serial number 16946 which places its production in 1875 and also places it in the desirable inspection range of “principle sub-inspectors” A.P. Casey, Samuel B. Lewis and an unknow inspector whose last name starts with “J”. These three men inspected US Model 1873 revolvers in the serial number ranges of 15,117 to 19,565. Based upon a limited number of extant examples, it is likely that based upon the serial number, this frame was originally inspected by Casey. During this period the frames did not receive a small sub-inspector’s initial mark, and this one shows no indication of having been marked in that way. The frames produced during this period (about #200-34,000) have the first type or “two date in two-line” patent date marking in addition to the “U.S.” ownership mark. This frame is correctly marked with this two-line marking,

– PAT. JULY, 25, 1871 –

– PAT. JULY, 2, 1871 –

followed by the U.S. ownership mark. The patent date marking is somewhat light, particularly the first line, with the second line more legible and the third remaining the crispest. The weakening of the mark is due to the factory polishing when Colt refinished the revolvers. The barrel is a mid-production part, being a David F Clark period barrel, with the partial serial number 1006 stamped under the ejector housing. Ordinarily this partial serial number would not be enough information to determine what the original barrel serial number was, but in this case the barrel also has a faint D.F.C. inspection mark on it, revealing that sub-inspector Clark inspected the barrel. Clark inspected single action revolvers in the two serial number ranges, with the early guns being found in the 41,033 through 43,300 range and the later ones being found in the much larger range of 53,006 through 121,238. The complete serial number of the barrel could have been one of several in Clark’s inspection range, including 61006, 71006, 81006, 91006, 101006, 111006 and 121006. This eliminates it from his early inspection group and means the barrel was made between late 1880 and 1887. The barrel has the “Type IV” barrel address, referred to by Kopec as the “Elongated Block Letter” address. This address was used on the mid-to-late production Colt Single Action revolvers, and according to A Study of the Colt Single Action Revolver by John Kopec, this marking is found between serial numbers 54,000 and 140,000. The barrel retains some of the original tiny P proof mark on its bottom, forward of the cylinder arbor pin, and about even with the ejector rod head cut out in the ejector housing. The barrel is also stamped with a P from when the barrel was re-proofed at the time that Colt refurbished the gun. This mark is placed over the original D.F.C. inspection. The barrel address remains quite clear and crisp for a refurbished gun, and as noted is the fourth type block letter address, and reads:

COLT’S PT. F. A. MFG. CO. HARTFORD CT. U.S.A.

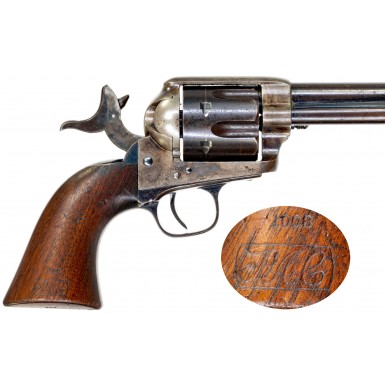

The triggerguard is serial numbered 8565 and the butt (backstrap) of the revolver is numbered in close proximity at 8850. Both of these are in the extremely desirable range of guns inspected by O.W. Ainsworth in 1874. A weak Ainsworth A sub-inspection mark is present on the triggerguard and on the top of the backstrap, behind the hammer. The cylinder is an un-numbered Colt factory replacement that is correctly marked with a Colt factory inspector’s K on the rear face. The loading gate of the revolver bear the typical assembly (aka “bin”) number found on most guns; in this case it is 611. The ejector housing is unmarked, which is typical as the numbering of this part was discontinued during the early Ainsworth era and while the part was to be inspected, rarely are examples found with the required sub-inspection mark. The ejector housing is a third pattern housing with the late production “kidney shaped” or oval ejector rod head. The earliest ejector housings (through about #18,600) had a small round metal stud about .2” in diameter that engaged a similar hole machined in the barrel of the revolver. This locating stud prevented the ejector hosing from moving if it was struck and kept the threads of the housing mounting screw from absorbing the impact and potentially shearing off. The hosing was secured with a screw that had a much larger diameter shoulder than the actual threaded area, so the screw hole on the inside of the housing was smaller than the hole on the outside of the housing. The housings after about #18,600 eliminated the locating stud and also made the mounting screw hole the same diameter all the way through, making the mounting screw thicker in the threaded area. Both these first and second type housings had the defect that there was no way to remove the ejector rod from the housing without first unscrewing the rod head from the rod itself. However, the third type housing added an additional machined slot at the rear of the housing that allowed the rod head to be rotated and removed from the housing without further disassembly. This third style rod housing appeared around serial #100,000. This gun has one of those “Type 3” housings. The large pattern oval ejector rod head is typically found on the guns produced during 1885 or after, with the change-over occurring in the 113,000 – 114,000 range. When the ejector rods were replaced during the refurbishment process, they were of the later, oval type. The hammer is a refurbishment replacement with the shorter civilian style checkering and the “early civilian” style cone shaped firing pin of the same pattern as found on the martial single action hammers. The one-piece walnut grip is a Colt factory refurbishment replacement, installed during the Colt reworking of the revolver. The grip is marked with a pair of small R.A.C. sub-inspection marks on the bottom of the grip, indicating that Rinaldo A. Carr inspected the grip and passed it for use. A crisp and clear RAC cartouche is present on the left side of the grip with a clear 1903 date above it.

So, the question is raised as to “what does all of the preceding information tell us about this gun?” We know that the 1874 era triggerguard and backstrap were originally parts of Cavalry Single Action revolvers inspected by O.W. Ainsworth and delivered in the pre-Little Big Horn period. The frame is from the following year, in the range of A.P. Casey inspected guns and again part of a gun delivered and likely in service prior to the Custer battle. The barrel is from the David F Clark period of inspection and was delivered between late 1880 and 1887. The balance of the gun is a group of un-dateable parts, probably a combination of original service parts, and correct later replacement parts, from the Colt refurbishment period of 1900-1903. Historically the major components of the gun saw frontier service during the height of the Indian Wars. Most of the major parts, other than the barrel, were likely to have seen the most action due to their very early production. Sometime around 1893-1894 the gun was returned from field service for storage, and statistically was mostly likely to have had its barrel shortened at Springfield during 1898. It is possible that the barrel was shortened by Colt but since more than 90% of the .45 caliber Colt revolvers altered to 5 ½” barrels were altered at Springfield, it seems quite unlikely. I have not been able to find this frame serial number in any of the references that I have available to me, but it seems quite likely that this gun was issued for service during the Spanish American War and probably for use during the Philippines Insurrection as well in its “Artillery” configuration. At some point in 1903 the gun was returned to Colt to be “cleaned & repaired”. It is at this point that the gun was refinished and received any necessary small parts to put it back into service. At the time it was inspected at Colt it would have received the new set of grips that it currently wears, cartouched by Rinaldo A. Carr on the right side. The gun was then most likely returned to the Springfield Arsenal and subsequently issued for service in the field again, likely in the Philippines.

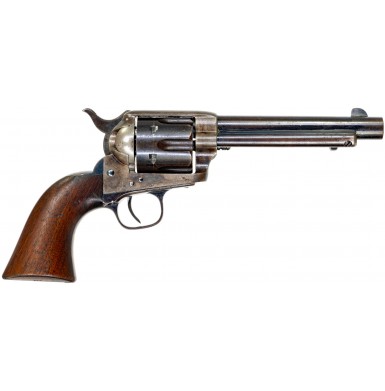

This Colt Single Action Army Artillery Revolver remains in about FINE condition. The markings on the gun are described in detail above, both the various parts serial numbers (if present), and their sub-inspection marks, as appropriate. The frame and barrel markings are also discussed above. As noted, some of the serial numbers and factory markings are partially obscured or worn away, primarily due to the necessary buffing and polishing required to refinish the revolver. It is my belief that the revolver was likely altered to the 5 ½” “Artillery” configuration at the Springfield Armory and was subsequently refurbished by Colt in 1903 as indicated by the grip inspection marks. The barrel retains about 15%+ of this period applied blue finish, which has thinned and worn along its entire length. The finish wear is completely consistent with real world use, as the areas of the deepest, best-preserved finish are in the protected areas along the top and bottom of the ejector housing where it meets the barrel, at the frame junction and around the cylinder arbor pin. The most consistent points of wear are holster related, along the top and left side of the barrel, at the muzzle and along the exterior edge of the ejector housing. The areas where the finish has worn have developed a mostly smooth plum patina that is very attractive. The barrel is mostly smooth, with some scattered pinpricking and minor surface oxidation present. Some freckles of darker brown oxidized discoloration are scattered throughout the remnants of the finish, which is typical of 19th century rust and nitre bluing but rarely encountered with modern finishes. The frame retains about 40%+ of the Colt factory reapplied color casehardened finish. The case colors still remain quite vivid in some areas with much of the frame color having dulled and faded from age. However, the frame remains very attractive. The frame is mostly smooth as well, showing only some very lightly scattered pinpricking and similar freckled areas of minor surface oxidation and discoloration as found on the barrel. The cylinder retains about 30%+ of its period blued finish. The finish loss is in the typical areas, at the leading edges and high points, with the overall loss appearing to be the result of flaking. The areas of the cylinder that have had the finish wear away have richly oxidized brown patina that blends well with the remaining blue and gives the cylinder a more plum appearance. The cylinder also shows some lightly scattered surface oxidation and minor surface roughness. The triggerguard retains about 40%+ of its blued finish, while the backstrap, butt and gripstrap all retain much less of their blued finish, probably closer to 20% at best. These areas show the expected wear and fading from handling and use, and have the same oxidized plum brown patina found on the other areas of exposed metal on the gun. The trigger retains some dull traces of fire blue on its edges but has a mostly dull blue-gray patina on its face. The hammer retains some minute traces of case coloring but has mostly dulled and faded to a brownish color with some part of the flats a dull silvery gray color. The revolver is mechanically functional but does need some mechanical attention. The half-cock notch will not engage, so the hammer must be held in that position to allow the cylinder to unlock and be rotated. However, the times, indexes and locks up exactly as it should. It is likely that the half-cock notch on the hammer has worn or chipped. The ejector rod functions smoothly, and the loading gate operates correctly, locking firmly into place when closed. The bore of the revolver is in about FINE condition as well. It is mostly bright and retains very good, very crisp black powder rifling along its length. The bore shows some light pitting scattered along its entire length with some tiny areas of more moderate pitting. A good cleaning might improve the bore condition even more. The one-piece grip is in VERY GOOD+ to NEAR FINE condition, and remains crisp, solid, and complete. The grip is free of any cracks, breaks or repairs. The grip shows the expected bumps, dings, and mars from service, use and storage, but no abuse. The grip primarily shows wear along its sharp edges at the base and to the sharp corners at the leading and trailing edges. These areas have worn down and are no longer sharp. There is also a minor chip missing from the lower leading edge of the left side of the grip. All of this is normal expected wear form use.

Overall, this is an extremely nice example of a Colt Single Action Army Artillery Alteration Revolver. The gun is particularly desirable because of it retains some nice blue on the barrel and cylinder as well as some attractive case coloring on the frame. The gun has a wonderful, honest appearance and displays very nicely. This is a high-quality example of an altered martial single action revolver that probably saw service for nearly 30 years, with the parts originally on the frontier fighting Indians during the 1870s and 1880s, then fighting in Cuba and eventually the Philippines. Considering the prices that marital Single Action revolvers have been bringing recently and how desirable the artillery alterations are becoming, this is a really very nice example of an interesting and historic revolver that would be a nice addition to any collection of post-Civil War 19th century US military revolvers.

Tags: Fine, US, Artillery, Alteration, of, a, Single, Action, Army, Revolver