Excellent British Pattern 1858 Native Cavalry & Mounted Police Carbine with Reference Collection Markings

- Product Code: FLA-3779-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

The best possible description of the British Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine is that it was a compromise; a carbine that no one wanted, and yet was the only logical solution to the current needs of the British military. The mid-19th century saw the British Board of Ordnance in a transitional phase, in fact the Board of Ordnance ceased to exist in 1855, being replaced by a section within the War Department. It is sometime around 1856 that we begin to see the changeover from the B (Broad Arrow) O Board of Ordnance storekeepers mark in the stocks of firearms, to the W (Broad Arrow) D War Department mark. This mark still conveyed the same information, that the gun was British military property, but was now marked by the War Department, rather than the Board of Ordnance. The year 1853 had seen the adoption of the Pattern 1853 “Enfield” Rifle Musket by the British military and had brought the most advanced muzzle loading, percussion ignition rifle musket of the period into use for all regular infantry regiments. An entire series of long arms for British military service would be spawned from the Pattern 1853 “Enfield”, including the Pattern 1853 Artillery Carbine, the Pattern 1856 and Pattern 1858 (and eventually the Pattern 1860 and Pattern 1861) short rifles, and the Pattern 1856 and later 1861 cavalry carbines. A secondary series of British “Native Troops” long arms based upon the Enfield would be also be developed, starting in 1858. The “Enfield” family of small arms was the first widespread adoption of a “reduced caliber” rifled long arm for a major world power. While the .577 bore of the Enfield does not appear to be “small” by today’s standards, it was somewhat revolutionary in concept for the period, as at the time most of the world’s powers still relied upon muskets and rifles that were nominally .69 to .71 caliber. The fact that the Enfield was rifled was revolutionary as well, as up until that time standard infantry doctrine called for rifled arms to only be issued to specialty troops and relied upon the smoothbore musket for the line infantry. Now, all British infantry would be issued rifled long arms.

During the early part of the 1850s, the British cavalry was armed with a variety of outdated and non-standard arms. The most widely issued was the Pattern 1844 Yeomanry Carbine, a .66 caliber smoothbore percussion weapon, and the next most common was the .66 smoothbore Pattern 1847 Padget Percussion Carbine, many of which were either converted from flint or made up from old flintlock parts, some of which still retained the Georgian era proof marks! Additionally, some Padget’s were rifled in an attempt to make them more modern, and several regiments serving in India, South Africa and Ireland used double-barreled carbines of various patterns that saw issue only to those regiments. None of the cavalry arms were standardized. Small arms standardization had been one of the goals of Board of Ordnance Inspector George Lovell, who had helped champion the modernization of British military small arms.

At the same time that the Pattern 1853 was revolutionizing the concept of the infantry musket, it was becoming clear that some form of breech loading rifled carbine was going to be the best choice to arm the cavalry. The problem was to decide which one. In 1855, a number of American made Sharps Model 1855 carbines were ordered for the British cavalry. These were delivered between May of 1856 and April of 1858, with a total of 6,000 of the guns seeing British service. All were issued to British regular cavalry regiments serving in India. In 1855, another American design was ordered as well, the Greene Patent Carbine. Over the next 18 months or so, some 2,000 of these carbines were delivered to the British military as well, but these arms saw only trials issue and service, and no real use in combat. Domestic designs were considered as well, including the Calisher & Terry breechloading carbine, and eventually the Westley Richards “Monkey Tail” breechloading design. None of these arms provided the solution the British military was looking for. In almost all cases the primary issue was with the ammunition. In the case of the Greene and Sharps carbines, the problem was that combustible cartridges that were sturdy enough to withstand the rigors of field service tended to be too tough for the carbines to use and detonate effectively, while those that were easily cut open by the Sharps’ breech block or pierced by the Greene’s firing pin shaped flash channel tended to fall apart in the cartridge box during regular field service. The Terry Carbine had accuracy and durability issues with its patent ammunition as well. Other patterns and designs of breechloading were also tested in smaller numbers, but none proved to be the answer the British were searching for. The end result was that in 1856 the Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine was authorized, a gun essentially based upon the carbine in service with the East India Company at that time and was thus known in service as the East India Service Pattern. The gun was a compact, muzzle loading percussion firearm with a 21” barrel with the service standard .577” bore. The carbine closely resembled the P1853 Rifle Musket that it was patterned after, with a blued barrel and barrel bands, color case hardened lock and brass furniture. The ramrod was of the captive design, mounted to stud under the barrel, near the muzzle, with a pair of swiveling arms. The rear sight was of the same pattern used on the P1853 Artillery Carbine and consisted of a fixed 100-yard leaf and two additional folding leaves for 200 and 300 yards, respectively. The sight had been developed by Thomas Turner as part of the design of the P1853 rifle musket and had originally been intended for use in conjunction with an adjustable long ladder sight regulated out to 1,000 yards. This pattern of sight was never officially adopted for general issue with the P1853, but the 3-leaf portion used for 100, 200 and 300 yards did see use on the carbines until a new sight was adopted for cavalry and artillery carbines in 1861. The carbine was 37” in overall length, and included an iron sling bar opposite the lock, secured to the stock with iron side nail cups that also secured the lock mounting screws. Although the majority of the P1853 family of arms utilized progressive depth rifling, the majority of P1856 carbine production did not, although the standard 1:78” rate of twist was retained in the carbine bores. In the end, in an era where even the US military had discovered that breechloading carbines were the wave of the future, the British military settled upon an essentially obsolete design and kept it in use for a decade, when it was finally replaced by the Snider carbine, the British version of the American “Trapdoor” system, that altered percussion muzzle loaders to breech loading cartridge guns.

In keeping with the standard British military doctrine of the period, the British military relied heavily upon local troops for much of their military needs in the various British colonies. Not unlike the Roman Empire, the British used a small number of regular army regiments that were mixed with much larger forces made up of local soldiers, but under the command of British officers. In India in particular, this system had been in place since the 1600s and the establishment of the East India Company. By 1857, the huge military force that enforced the will of the British Crown in India consisted of roughly 36,000 regular Army British soldiers and some 233,000 Native Troops under the command of British officers. This ratio of more than 6 Indian Natives to 1 British Regular Army soldier was not considered problematic, until later that year.

The Indian Mutiny, sometimes referred to as the Sepoy Rebellion was a massive 1857 uprising of the native Indian Troops against their British rulers. The causes of the rebellion multi-faceted but one of the “straws that broke the camel’s back” was the fact that earlier that year the new Pattern 1853 Enfield had begun to be issued to the Sepoys. The problem was that the Enfield cartridge was lubricated with tallow, essentially a rendered mixture of animal fat. Both beef and pork fat were components in the mixture that was chosen by the Board of Ordnance for its ready availability and its economy. To the Indian Army, composed primarily of Hindus and Muslims, this was an impossible situation. The cow was sacred in the Hindu religion and its eating was forbidden. Pork was unclean in the Muslim religion and its consumption was equally forbidden. As British doctrine required the soldier to tear the cartridge with his teeth, this meant Hindus placing beef in their mouths and Muslims placing pork in their mouths. This was unthinkable for both religions and became the spark that ignited an uprising that was much more about some 250 years of English domination than the components of the cartridge lubricant.

The rebellion was extremely bloody and lasted roughly a year. Although the British forces were substantially outnumbered, the use of the advanced Enfield pattern rifled weapons gave them a substantial advantage over the Sepoys. More than one British officer noted that if the Sepoys had been fully rearmed with the new Enfield before the rebellion, the British would most certainly have lost. As a result, the British adopted a policy of keeping the Indian native troops armed with weapons that were at least one technological advancement behind the British regular army. This resulted in the new series of Native Troops arms that were based on the Enfield. These guns were made to the same basic quality of fit and finish of the regular army weapons, and to the casual observer were the same pattern of arms but were smoothbore rather than rifled and were equipped with a simple block, fixed rear sight rather than an adjustable one.

The first series of Native Troops arms adopted were the Pattern 1858. For all practical purposes these were almost identical to the Pattern 1853 series but were smoothbore and .656 caliber rather than rifled and .577 caliber. As noted, the rear sight was a fixed sight. A slightly improved version of the Pattern 1858 Musket was adopted in 1859 with a thicker barrel, but for mounted use, the Pattern 1858 Native Mounted Police Carbine would remain in use for Indian cavalry, mounted troops and mounted police well into the late 19th century when the British regular army cavalry regiments were armed with Snider and eventually Martini-Henry Breechloaders.

The Pattern 1858 Native Mounted Police Carbine was initially produced by the various Birmingham and London arms contractors to the War Department but eventually was produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock (R.S.A.F.) as well. Externally the gun was nearly a direct copy of the Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine, with the only obvious difference being the use of a fixed rear sight rather than the small folding leaf sight. Internally, the primary difference was that the Native Mounted Police Carbine was a .656 caliber smoothbore gun, rather than a .577 rifled arm.

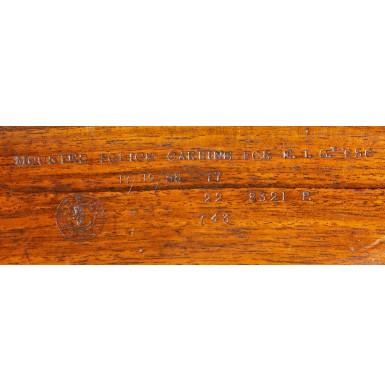

Offered here is an EXCELLENT example of a Pattern 1858 Native Mounted Police Carbine produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield in 1866 that is marked as a sample gun, in the same manner as the Sealed Pattern guns in the collection of the Royal Armories, with only the wax seal not present. The gun is stamp marked clearly in four lines on the butt:

17/12/58 77 77

22 8321 P

743

The markings reveal the pattern (model) of the gun and caliber, over the date of adoption, December 17, 1858, with additional information which may indicate how many were produced (8321?). The butt also includes a cartouche on the obverse butt that reads -R {CROWN} M-ENFIELD in a circle around a small {CROWN}/GS/M in a circle. This is the same inspection mark found on the Colt Model 1851 Navy Revolvers acquired by the British circa 1866-1867 which may have then been sold to Egypt. The mark is not a standard RSAF Enfield cartouche nor a British military storekeeper’s mark, but rather seems to indicate British government inspection for use and service and I now believe it indicates inspection for use by a British colonial government. While the external “R M ENFIELD” marking indicates the Royal Manufactory at Enfield, a standard British military gun would have a small {BROAD ARROW} / WD in the center of the mark. Interestingly, this same {CROWN}/GS/M inspection mark is present on the nocks form on top of the barrel’s breech and on the side of the hammer nose. The carbine is 100% complete and correct in all ways and since it is an interchangeable parts gun produced at RSAF Enfield, there is no need for mating marks on the various part and none are present. The lock is crisply and clearly marked {CROWN} / VR to the rear of the hammer and 1866 / ENFIELD forward of the hammer. There is also a small British military {CROWN} / {BROAD ARROW} on the forward portion of the lock, below the bolster. Other than a small Enfield inspection mark the interior of the lock is unmarked. The breech of the carbine is marked with a variant of Victorian era British military proofs, a {CROWN}/VR over {CROWN}/{CROSSED PENNANTS}, typical of arms produced at Enfield starting the latter part of the 1860s, when the crossed pennants replaced the crossed scepters that had been used for many decades.

As noted above, the overall condition of the carbine is about EXCELLENT. The gun retains about 90%+ of its original deep, dark, rust blued finish on the barrel, with some minor thinning and wear and some freckled oxidation here and there and small flecks of oxidation shot through the blue. The most noticeable freckling is along the sides of the barrel where it meets the stock. The barrel is free of any pitting at all and is extremely smooth, with only some freckled oxidation noted. The bore of the gun is EXCELLENT as well and remains mostly mirror bright with some scattered light surface oxidation and some discoloration and some freckles of surface roughness. A good scrubbing would likely result in an essentially mint condition smoothbore barrel. The lock of the gun retains about 80%+ of its original color case hardened finish, which remains partly vivid with some dulling and fading. The hammer has lost most of the case color and has faded to a silvery gray with traces of original mottling. The lock is mechanically excellent and functions perfectly on all positions. The original block rear sight is present, and the original front sight is in place near the muzzle as well. The original sling bar and ring are present on the flat of the carbine, opposite the lock, and remain fully functional. The original swivel ramrod is in place in the channel under the barrel as well. The rod works smoothly, exactly as it should. The stock is in about EXCELLENT condition overall and remains extremely crisp. The stock has never been sanded and retains extremely sharp lines and edges where it should. The stock is full-length and solid with no breaks or repairs noted. The markings in the obverse butt remain clear and crisp and fully legible. The stock does show the usual assortment of bumps, dings, rubs and minor blemishes from handling and storage, but nothing significant or abusive.

Overall, this is a really fantastic, 100% complete and correct example of a Pattern 1858 Native Mounted Police Carbine in an extremely high state of preservation. The gun has amazing eye appeal and is a really wonderful, high condition example with nearly all of original finish. While examples of the Native Police Carbine do appear on the collector market from time to time, they are invariably well-worn, well-used and retain no finish at all. This one is truly exceptional. The markings on this example suggest it was a sample gun pulled from the 1866 production run at RSAF Enfield and was kept for reference and as a production quality sample. Clearly, it cannot be a “sealed pattern” gun as it was produced eight years after the pattern was adopted and has no Ordnance wax seal. It was, however, likely retained as a sample by the War Department for their Ordnance collection, based on the markings. The series of Native Troops arms produced by the British during the 3rd quarter of the 19th century are a very interesting group of guns. They represent one of the few times when military arms were intentionally produced in a way as to be less effective than they could have been and were clearly an attempt by the British to walk the fine line between arming their colonial troops with functional arms, but not so well as to enable them to overthrow their imperial overlords. This would be a fantastic example of a British Native Troops carbine to add to any advanced collection of British military arms from the 19th century.

SOLD

Tags: Excellent, British, Pattern, 1858, Native, Cavalry, &, Mounted, Police, Carbine, with, Reference, Collection, Markings