Alexander Henry Retailer Marked Pryse & Cashmore "Daw" Revolver with Very Rare Topstrap

- Product Code: FHG-2222-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

In 1855, Birmingham gunmaker Charles Pryse and West Bromwich (Staffordshire) gunmaker Paul Cashmore received British Patent 2018/1855 for a self-cocking revolver mechanism and various improvements to revolver designs as well as improvements to loading levers for revolvers. This patent would become the basis for what collectors refer to as the Daw revolver, a gun that is typically attributed to George H. Daw of London but was never actually manufactured by him. The Pryse & Cashmore design was for an open top percussion revolver with a somewhat unique double-action lock work. Like a traditional “self-cocking” revolver could be cocked and fired with a single long pull of the trigger. Likewise, the revolver could also be cocked manually and then fired by pulling the trigger in a conventional single action mode. Usually, these two methods of operation taken together are considered a traditional double action revolver. The lock work, however, had an additional feature in that pulling the trigger slowly, about halfway to the rear of its full travel, allowed the hammer to engage a notch that left the revolver in a half-cocked position and the cylinder partially indexed. This allowed the cylinder to be rotated manually for loading, but also allowed a shooter to take deliberate aim, and then finish the firing sequence by finishing the trigger pull, which indexed and locked the cylinder, fully cocked the hammer and then released it to fire. This half cock position along the trigger pull pathway reduced the weight and length of the double action pull and gave the revolver the speed advantage of a double action (or self-cocking) revolver as well as the improved accuracy of a single action type trigger pull. This action was in some ways similar to the “hesitating action” used in early Adams and Tranter revolvers. The revolvers were percussion ignition with cylinders that rotated in a counter-clockwise direction. There were three major components to the revolvers: the frame, the cylinder and the barrel, which also included the loading lever assembly. The barrel was secured to the frame via a transverse wedge that entered from the right side of the gun (Colt’s entered from the left side) and passed through both sides of the barrel web and the cylinder arbor pin. An interesting feature of the design was the “U” shaped notch on the lower face of the hammer nose that was designed to rest upon safety pins on the rear face of the cylinder, between the chambers. This allowed the revolver to be safely carried with a fully loaded cylinder, with the hammer down on a safety pin. This was similar to the safety pin system found on Colt revolvers of the period, but was somewhat more elegantly executed, making the system more secure and reliable.

Like most English revolvers of the era, the Pryse & Cashmore revolver was available in a variety of frame sizes and calibers. The standard models were “Holster” in 38 bore (about .50 caliber), “Army” in 54 bore (.443”), “Navy” in 80 bore (.387”) and “Pocket” in 120 bore (.338”) and it is even reported that a diminutive 240 bore (about .28 caliber) pocket model was produced as well. Barrel lengths varied with caliber with the longest barrels being utilized on the larger calibers. 38 bore revolver barrels were typically about 6 ½” in length, although examples over 8” long are known. The standard “Army” barrel was 6 ½”, the standard “Navy” barrel was 5 ½” as was the standard “Pocket” barrel. Of course, variations could and did occur, with special order barrel lengths and calibers available. The largest calibers were only available with a 5-shot cylinder, while the 120 bore guns had a 6-shot cylinder. One variant of the 80 bore revolver was available with a solid frame, rather than an open top, and this gun was available with a 6-shot cylinder as well. Interestingly a “solid frame”, although still a two-piece wedge retained frame, 54-Bore gun recently turned up on American soil.

A variety of loading lever systems are encountered on the Pryse & Cashmore revolvers, including those patented as part of the original revolver design, as well as a design patented by Thomas Blissett. It is believed that about 5,500 of the Pryse & Cashmore patented percussion revolvers were produced circa 1855 to 1865, with the large majority of them being retailer marked by George Daw. A handful of early examples are known with other retailer marks, but Daw was certainly involved with the marketing of the large majority of the guns. To that end he engaged in a relentless campaign to get the revolver design into the public spotlight by arranging reviews and commentary in such publications as The Times and the 1860 edition of Hans Busk’s book The Rifle and How to Use It. In another period book, The Book of Field Sports author Henry Miles noted of the Pryse & Cashmore revolver: “its form is of the handsomest, its finish exquisite and it is one of the pleasantest in the hand of the many varieties of revolver we have examined.” In a further attempt to garner press and praise, Daw presented one of his rifles and a Pryse & Cashmore revolver to Italian revolutionary leader General Garibaldi in April of 1864, with an accompanying story about the engraved presentation pieces being published in the April 22nd , 1864 edition of the Daily Telegraph. Despite his tireless promotional efforts and the fact that nearly all examples of these revolvers are retailer marked by Daw, it appears that all revolvers were actually manufactured by Pryse and/or Cashmore.

Charles Pryse had established himself as a gunmaker on St. Mary’s Row in Birmingham in 1838 and became Charles Pryse & Company in 1840. In 1842, the firm of Pryse & Redman was formed, located at 84 Aston Road, and would remain in business through 1871. During the Civil War era, Pryse & Redman would manufacture a substantial number of Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets, many of which would go to fill contracts for the Confederacy and likely the Union as well. The firm of Charles Pryse & Co would reappear in 1874 and would remain in business through 1883. In 1886, the firm would reorganize as Thomas & Lewis Pryse (his sons) and remain in business in one form or another through 1904.

Paul Cashmore established himself as a gunmaker in Churchfield, West Bromwich, Staffordshire in 1849 and moved to the Newton Street Works, Old Church in 1854. He would remain there until 1878 and would last be listed in period directories in 1883. As there is never any indication that Pryse and Cashmore ever operated out of the same premises (or even in the same town) it is unclear if only one, or both of them were producing the Pryse and Cashmore patent revolvers. However, all of the noted authors on the subject (particularly A.W.F. Taylerson) note that Daw was not the manufacturer of the guns. It appears the guns were manufactured by Pryse and/or Cashmore and delivered to Daw “in the white” for “finishing and stocking”, allowing the level of embellishment and finish to be customized to the market. Daw would also case the revolvers and provide accessories, as required. Taylerson notes that period advertisements for the Daw retailed Pryse & Cashmore revolvers listed: “Army, Navy & Pocket sizes in Holster case, extra nipples, Bullet Mould & c. from £6.10.00. Ditto in oak case and apparatus complete £7.10.00. Ditto highly finished £10.10.00. Revolving Rifles from £15.00.00.”

Although the makers and retailer had hopes to receive military contracts from the British government for their revolver, this never happened. The reasons were likely two-fold and interrelated. First, the guns were not manufactured on the basis of interchangeable parts and were mostly hand fit and assembled. This meant it would be difficult to repair them in the field and that a substantial amount of skilled labor was involved in their manufacture. Secondly, these labor costs were reflected in the prices charged for the revolver, making them less enticing to a parsimonious War Department. This same set of circumstances were directly responsible for the War Department’s lack of interest in Philip Webley’s “Long Spur” revolver design from the same period. The retail price of a Colt Navy revolver during the same period in England was only £5.10.00 (uncased but with mold) and Joseph Brazier was offering Adams’ patent pistols for between £4.10.00 and £5.10.00. In both cases a much more robust military pattern revolver was available to compete with the Pryse & Cashmore offering for less money. As such, Daw concentrated on offering the revolvers that usually bore his name to the commercial market. George H. Daw first went into the firearms manufacturing and retailing business in 1851 as a partner in Witton, Daw & Company, located at 82 Old Broad Street in London. John Sergeant Witton had established himself as a London gunmaker in 1835 and had worked under his own name until this partnership was established. In 1853 the firm moved to a new location at 57 Threadneedle Street, and in 1854 was renamed Witton & Daw, dropping the “& Co”. In 1860 George Daw took over the firm, changing the name to George Henry Daw (or simply G.H. Daw) and operating under that name 1880, when it was changed to G.H. Daw & Co. The firm remained in business in a number of locations through at least 1889, and may have remained active as late as 1892, but it is not clear if this “Daw Gun Company” had originated with original Daw business. Daw is probably most famous, although rarely remembered for, the introduction of modern “Boxer Primed” centerfire ammunition to Great Britain in 1861. Daw acquired the British patent rights to the French patent of Francois Schneider, whose design had been further improved by Clement Pottet. Unfortunately, the French patentees did not keep their patent rights in force in France, thus removing any protection that Daw had acquired by buying their rights for patent in England. He was sued by Eley Brothers, the largest ammunition manufacturer in England, and it was found that since the French rights no longer protected the patentees, they had no rights to sell to Daw, leaving him with no protection in England. Although Daw lost his case (and his investment in the patent rights), he was still directly responsible for bringing easily reloadable, modern center fire ammunition to England. Daw’s greatest financial successes in the gunmaking business would come in the post-percussion era, with his manufacture of high quality cartridge revolvers, rifles and shotguns.

Offered here is a VERY GOOD+ to NEAR FINE example of an incredibly scare solid framed Pryse & Cashmore Revolver that has a topstrap. While still a two-piece revolver with a wedge retained barrel, the frame is more akin to that used on the Webley Wedge Frame revolvers as it includes a topstrap, but still clearly uses the Pryse & Cashmore “Daw” pattern mechanism. The lovely revolver is wonderfully engraved with tight foliate scrolls on the frame and with small embellishments on the lower front of the frame, where the barrel meets the cylinder and on the butt cap. Additionally there are neatly executed geometric boarders around the topstrap and the lower edges of the frame. The gun was retailed by the famous Scottish gunmaker Alexander Henry (1818-1894) of Edinburgh. Henry was apprenticed to the famous English gunmaker Elsworth Mortimer in 1836, eventually becoming Mortimer’s shop manager. In 1853, Henry established his own gunmaking business as 12 South St. Andrew Street. He moved to 8 South St. Andrew Street in 1858, returning to the #12 location in 1862. Henry is probably most famous for inventing a form of rifling. He received British patent #2802/1860 in 1860 for his rifling design. He incorporated it into target rifles that he built, and it was so successful that the British military adopted it for use in their new Martini falling block action rifles in 1871. The Martini rifles were to replace the older Snider breechloaders, and after adopting Henry’s rifling pattern became known as the Martini-Henry rifle. The following year, in 1872, Henry was granted the title of Gun & Rifle Manufacturer to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. After his death, his son, also named Alexander, maintained the business until 1909.

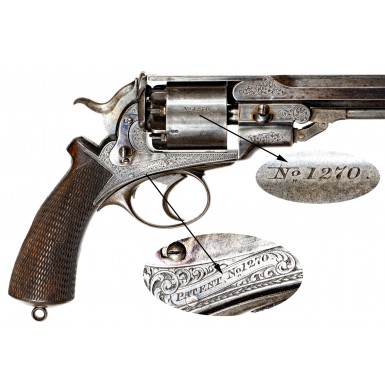

The revolver’s topstrap is clearly engraved ALEXR HENRY, EDINBURGH. The lower right side of the frame is engraved in a ribbon PATENT No 1270, a relatively low serial number considering some 5,500 Pryse & Cashmore patent revolvers were produced. The cylinder is engraved No 1270 as well, matching the frame.

The revolver is assembly numbered 64, an indication of the non-interchangeable, handmade nature of the design. The assembly number is readily visible on the bottom of the barrel under the loading lever, on the loading lever, on the rear face of the cylinder and on the wedge. Disassembly would likely reveal more assembly numbers. The frame also incorporates an interesting sliding safety that I have not encountered before, which engages a slot machined in the ring surrounding the ratchet on the rear of the cylinder. The safety can only be engaged when the hammer is in the half-cock position, and locks the gun completely, preventing any action at all. According to The Revolver 1815-1865 by Taylerson, Andrews & Frith, this safety mechanism that is only infrequently encountered, was described in the Pryse & Cashmore patent application. The lower left angled flat of the octagonal barrel is marked forward of the barrel web with the commercial London proof and view marks of a {CROWN} / GP and {CROWN} / V. Additionally, alternating {CROWN} / V and {CROWN} / GP London proof house marks are also found between the chambers of the cylinder. The presence of the London proof marks on the revolver suggest that although the guns may have been manufactured and delivered in an unfinished state to Daw by Pryse and Cashmore, he was still responsible for the proving of the guns. If the guns had been proved by the makers, they would have been marked with Birmingham commercial proof marks, rather than those of the London proof house. This additionally indicates that Alexander Henry was only the retailer, unless he sent the guns he produced to the London Proof House for proving. Like so many English revolver, the chambers are numbered, in this case on the face of the cylinder. The revolver is a classic 54-Bore (.443” caliber) revolver and has a 6” octagonal barrel. The rear of the barrel measures .445”, while the muzzle is a much tighter .438”. The five chambers vary from .445” to .451”. The earlier production Pryse & Cashmore revolvers show the greatest variation from the norm in terms of calibers and barrel lengths and this revolver is no exception. Later production examples tend to have round rather than octagonal barrels, and as previously noted the “Army” sized revolvers would be more standardized 6 ½” barrels. The action of the revolver functions flawlessly, and the pistol times, indexes and locks exactly as it should. The original loading lever is present and functions smoothly also. The lever is a good example of one of the types patented by Pryse & Cashmore as part of their 2018/1855 patent.

The gun remains very crisp and sharp throughout. It retains about 20%+ of its original blued finish overall. The blue is streaky and thinning and is mostly present on the barrel, but also appears in some protected areas on the frame. The hammer retains about 20%+ of its original brilliant fire blued coloring in the protected areas, with most of the hammer having dulled and faded. The trigger is similarly finished and retains some traces of fire blue as well. The triggerguard has flaked quite a bit and has lost the majority of its original blued finish. The buttcap, loading lever hinge & plunger and backstrap were all originally color casehardened. The loading lever retains some dulled traces of case color near the frame, with the balance mostly a dull pewter patina. The butt cap has a rich, deeply oxidized brown patina. As noted, all of the markings and engraving on the pistol remain extremely sharp and crisp, as do the edges of the barrel and the frame. Like many English revolvers of the era, this one has a lanyard ring in the butt cap. The metal is mostly smooth, with freckled oxidation scattered along the barrel and on the frame, with some flecks of minor surface roughness here and there. Despite this, the quality of the engraving is clearly apparent. As noted in the advertisement noted above, this example was likely one of the “highly finished £10.10.00” revolvers, as it is factory engraved and is a truly delightful example of the British gun maker’s art in the early 1860s. The frame is decorated with delicate and expertly executed foliate scrolls that cover about 80% of its surface. Unlike most foliate scrolls of the period these are tight, although not “banknote” tight, and not the usual loose and open scrolls more commonly encountered. The muzzle and forcing cone of the barrel are engraved en-suite, with coverage that only extends for about ¾” to 1” in either direction. The bottom of the triggerguard and backstrap are engraved in a similar manner, and the butt cap is engraved with a geometric floral motif. The original German silver cone front sight is present on the top of the barrel, near the muzzle, and remains full height with the original crowning at its end. The original fixed notch rear sight is present at the rear of the barrel, just forward of the cylinder. The bore of the pistol is in about VERY FINE condition and remains extremely bright and sharp. The bore retains very crisp, narrow 5-groove rifling, and shows only the most minor traces of lightly scattered pinpricking and some light pitting; mostly in the grooves. The one-piece checkered walnut grip is in about FINE condition as well. It retains extremely sharp checkering over most of its surface, with only the most minor indication of handling and light use. The grip is free of breaks, cracks, chips or repairs, and has a rich chocolate brown color. A lovely German silver lozenge shaped escutcheon is set into the rear of the backstrap for the engraving of a monogram but is remains blank. The grips is nicely checkered to leave a blank, un-checkered diamond pattern around the escutcheon. Overall, this is a really a wonderful example of a relatively early production Factory Engraved Pryse & Cashmore “Daw” Revolver with an extremely rare “solid” frame with a topstrap and an equally rare sliding safety on the frame. The pistol is in NEAR FINE condition with some nice original blue remaining and with exquisite engraving that is really very attractive and must really be seen in person to appreciate. While Pryse & Cashmore revolvers can be found for sale from time to time in England, they are extremely scarce in America. Examples with topstraps are even more rare, and this is the only “Army” sized example I have ever seen in person. The gun is absolutely 100% complete and correct in every way and is in perfect mechanical condition. This will be a stunning addition to your collection of English percussion revolvers and is a gun that I know you will be very proud to own.

SOLD

Tags: Alexander, Henry, Retailer, Marked, Pryse, Cashmore, Daw, Revolver, with, Very, Rare, Topstrap