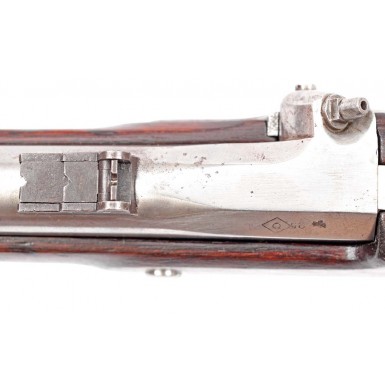

During the American Civil War the US government entered into contracts with more than two dozen firms to produce the US M-1861 (or M-1861 Special Model) rifle musket. While the majority of those contracts were filled with a minimum of trials and tribulation, some were cancelled in mid-stream due to delays and low production. Some contractors barely delivered any arms at all, and had their contracts nullified, and some were cancelled before they ever started production. Most of the contracts are well documented and are often contained within the Congressional records that cover the investigations into slow and unfulfilled Civil War military contracts. Eli Whitney Jr. received multiple US military contracts during the war to provide both the M-1861 Rifle Musket and the M-1861 Naval Rifle. However, his experience in producing the M-1841 “Mississippi Rifle” for the US Ordnance Department had taught him that US government contracts, with their strict gauging and inspection of the arms, resulted in many guns being rejected (or accepted at a much lower price) and were a less profitable endeavor than producing lower quality, non-interchangeable parts guns for the states, who would not inspect the guns nearly so scrupulously. As a result, much of Whitney’s Civil War era long-arm production was focused upon making and selling his “Good & Serviceable Arms” to the states, as it was much more profitable than dealing with the Federal government. Whitney regularly used surplus, condemned and rejected parts to assemble these arms, resulting in guns of 2nd class quality at best and sometimes even worse. His most notorious “scam” was in the production of this “Manton” marked M-1861 rifle muskets. For many years collectors assumed that the Manton marked contract arms were produced in England. This theory was supported by the use of the name of a well-known London arms maker, the Old English font used to stamp the name on the lock, and the fact that many of the early “Manton” muskets were delivered with British proved barrels. In fact, the barrels were British made (most by Ezra Millward, with some by Henry Clive), but had been purchased by Colt, with the expectation of using them for US musket contracts. Colt subsequently dumped the barrels on the open market and Whitney purchased 4,060 of them, which they used in the assembly of a variety of long arms. These 40” long barrels were produced in Birmingham and typically bore a single Birmingham commercial proof at the breech, along with a gauge mark like 24 or 25, which indicated the caliber of the bore. At least some of these barrels were also stamped with the mysterious “Diamond C” mark at the breech. For years the exact meaning of this mark has been debated among Civil War arms researchers, as to whether the < C > mark at the breech really meant “Colt”, or possibly “condemned”, or had another meaning. The confusion has been exacerbated by the extant examples of Confederate marked Enfields with non-standard 40” barrel that also have the < C > mark on their breech. All of the 2nd Contract Sinclair, Hamilton & Company Confederate Enfields marked with a JS/Anchor in the 9,000 / A to 9999 / A range have these 40” Diamond-C barrels, as do the first 1,000 JS/Anchor marked South Carolina contract P-1853s. Other examples outside these two large batches are also known with Diamond-C barrels. I can now confidently say that I am positive that the Diamond-C mark indicates that the barrel was a Colt contract barrel, and this Manton musket is a testament to that fact. Whitney devised the whole “Manton” ploy to distance his company from what he clearly felt was an inferior quality arm. Whitney admitted this himself in a February 2, 1863 letter to the R.S. Stenton Company of New York, when he said in part: “I can not promise more than 1,000 of the “Manton” muskets and these only to be subject to State Inspection as good an serviceable work being as a general thing as the sample, and if any are rejected it will lessen the number so much (from 1,000). My object in putting the “Manton” on the lock was to avoid selling the muskets as mine.“. I have underscored that last line to emphasize that Whitney clearly did not want to associate his name or company with the “Manton” marked muskets. Whitney’s letter to the Stenton Company was in reply to their request to purchase “Manton” muskets. Whitney had submitted a least a handful of sample guns to both the RS Stenton Company and arms sellers William Bailey Lang & Company. A follow up letter from Whitney to William Bailey Lang & Co further stresses that Whitney does not want to be recognized as the “source” for these guns> The letter also shows Whitney “backtracking” about the features of the guns that he would provide, when compared to the “samples”. His letter to William Bailey Lang & Co reads in part:

“You can sell the 1,000 “Manton” U.S. muskets (but not as my manufacture) “tho as good as sample at $16.00 each.”

The underlined emphasis is mine, but his reference to the guns both as “US muskets’ and “ “tho as good a sample” suggests that some of the features of the sample guns were not quite the same as those he intended to deliver. This suggests that the arms delivered under the “Manton” contract were not even as good as the handful of sample rifle muskets. In a letter to June 18 letter to New York arms dealers Fitch & Waldo, Whitney said that he had on that day sent them “a sample Springfield gun, 1,000 of which I can furnish in on day’s time” These guns are good & serviceable, though varying slightly from the Springfield gauges in points not essential.”. Whitney also attempted to sell his “Manton” guns to the state of New Jersey, and to arms merchants Palmers & Bachelder, each of which was no doubt provided with a “sample” gun. It is not clear exactly how many of these “Manton” marked arms Whitney actually managed to sell, but surviving records indicate that 1,070 of them were sold to the New York retailer Fitch & Waldo between June 29 and August 4 of 1863. Fitch & Waldo subsequently sold the guns to the state of New York, who issued them to the volunteers that were called out to suppress the draft riots during the summer of 1863. Of those 1,070 guns, 109 were rejected by the state of New York. It is not clear how many more of these muskets were manufactured, but Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Arms notes that they are “quite scarce” and estimates that less than 2,000 were produced.

The “Manton” contract guns were made up from a variety of parts, many of which are thought to have been at least part of the 581 rifle muskets that were rejected by the state of Connecticut from the initial Whitney delivery of 1,440 arms between January 27 and April 11, 1862. It is for this reason that the “Manton” marked guns exhibit a variety of mixed features. The guns generally conform to M-1861 style that was produced for Connecticut under the first contract, but inconsistency is the only consistent feature of the arms. They are found with both 39” and 40” barrels, some with British proofs, some with US style proofs and some with the inspection mark G.W.Q. as found on Connecticut contract barrels. Some of the barrels have Whitney 7-groove rifling and some have 3-groove rifling, although they generally all have a Whitney style batch or serial number (a letter over a 1, 2 or 3 digit number, or sometimes next to it) stamped on the top of the barrel to the rear of the front sight. The guns typically have Whitney “mid-range” L-shaped rear sights, are iron mounted and have pewter forend caps. Some of the barrel bands are marked with the letter “U” for “up” but many are not. The majority of the guns have no “US’ on the buttplate tang, although Whitney’s use of pieces and parts from a variety of contractors and suppliers sometimes results in a marked buttplate. Most locks are simply marked Manton, with no date, although some 1862 (or more rarely) 1863 dates are found stamped vertically at the tail.

Overall this is a really great example of one of the hardest “contract” M-1861 rifle muskets to find. This is a real Manton, and not one that has been “put together” or assembled from incorrect parts. A Manton marked musket is an important centerpiece for any collection of Whitney arms, and is often one of the highlights of any collection that focuses on the variations of US M-1861 contract rifle muskets. Manton muskets rarely appear on the market for sale, and in the words of the late Norm Flayderman are “quite scarce”. This gun is particularly important, as its Diamond-C marked barrel helps to concretely establish that the mysterious mark refers to Colt.