In 1857 The firm of E. Remington & Sons of introduced their first percussion revolver. Since the founding of the firm in 1816 by Eliphalet Remington, the company had concentrated on the production of gun parts, and then long arms. The first products were gun barrels, then gun furniture and then finally complete flintlock rifles were added to the product line. In 1845, Remington acquired a contract for 5,000 US M-1841 “Mississippi” Rifles that had originally been granted to John Griffiths of Cincinnati, which he had defaulted on. The Ordnance Department was so pleased with the product delivered by Eliphalet’s company that he was granted two additional contracts for M-1841s, eventually delivering some 20,000 of the rifles to the US government over the course of a decade. Remington apparently saw the influx of government contract money as steady stream of income that would allow him to expand his business, and he soon sought additional US contracts. The same year as the Mississippi Rifle contract, he acquired a contract to deliver 1,000 Jenks Naval Carbines, with the newly devised Maynard Patent tape priming lock. Remington purchased the necessary machinery from the Ames Company of Chicopee, MA, who had delivered the first variation of the carbines and rifles, and who no longer needed the equipment. However, it was clear that the technological evolution of firearms was heading toward repeating arms, and to that end the company began to pursue percussion revolver production. In 1856, with the addition of Remington’s three sons to the business, the firm officially became E. Remington & Sons. The following year, their first revolver was ready for sale, the Remington-Beals Pocket revolver. This was the invention of Remington employee Fordyce Beals. Beals had been instrumental in the production of the Jenks carbine contract, and had actually been acquired from Ames, as had the machinery, as part of the negotiated arrangement between Remington and Ames. Beals’ design was a compact, single action, .31 caliber revolver that bore a resemblance to the “Walking Beam” revolver then in production by Whitney. This should come as no surprise as the Whitney revolver was based upon Beals’ 1854 patent which evaded Colt’s protection of his pistol’s mechanism. In 1856, Beals patented the features that were salient to his new Remington revolver, and in 1858 patented the cylinder pin and loading lever system that would define the profile of all the large-frame Remington handguns through the 1880s.

Beals’ 1858 patent (#21,478) was granted on September 14th of that year, and covered the winged cylinder arbor pin that secured the cylinder to the frame, which was retained by the loading lever located under the barrel, and could be withdrawn from the frame when the lever was lowered. Thus began the evolution of the second most used US marital revolver of the American Civil War. The first guns were produced in .36 caliber and production started to roll off the assembly line during late 1860 or early 1861. The .36 caliber “Navy” revolver was followed by a .44 caliber “Army” variant soon thereafter. By the time Beals-Navy production ended in 1862, some 15,000 of the handguns had been produced, while only about 2,000 of the larger “Army” revolvers were manufactured, before the Model 1861 pattern Remington revolvers superseded the Beals model. Of those 15,000 Beals Navy revolvers, several thousand were acquired by the US Ordnance Department, but primarily on the secondary commercial market and not directly from Remington. According to John D. McAulay’s research the firm of Cooper & Pond sold 600 Beals Navy revolvers to the US government during 1861. The Ordnance Department also acquired additional Beals Navy revolvers from Schuyler, Hartley & Graham and from Tyler, Davidson & Co, each of whom delivered 850 and 2,549 guns respectively. McAulay further notes that between August 17, 1861 and March 31, 1862 an additional 7,250 Beals Navy revolvers were purchased by the government on the “open market”, bringing the total US non-contract acquisition of Beals Navy revolvers to 11,249. As these guns were not part of a government contract they were not marked or inspected in any way, making it impossible to differentiate between those that was US purchases and those that were not. The only exception to this are the Beals Navy revolvers that ended up in US Navy inventories that were marked during the “reinspection” process circa 1864-1866. A small number of US Army martially marked examples are known in the 13,000 to 15,000 serial number range, and it is possible that these guns may have been delivered as part of a subsequent contract with Remington in June of 1862 for 5,000 .36 caliber revolvers. This seems most likely as they are in the serial number range of the final production of this model. Assuming about 500 of the Beals Navy revolvers were so marked (based on Flayderman’s estimate) that brings the total US procurement of the revolvers from 11,249 to around 11,750, or about 78% of the total production of the guns.

The Beals Navy Revolver was Remington’s first large frame, martial handgun to make it into production. The earlier Beals “Army”, a scaled-up version of the pocket model, was only produced as a prototype and it is believed that less than 10 were manufactured. The Beals Navy was a single action, 6-shot revolver with a nominally 7 ““ octagonal barrel that was screwed into the solid frame. While most references list the barrel length as 7 ““ some of the earlier examples measure closer to 7 3/8” in length. The guns were blued throughout, with brass triggerguards and a color casehardened hammer. The gun had two-piece smooth walnut grips, secured by a screw that passed through German silver escutcheons and a cone shaped German silver front sight was dovetailed into the top of the barrel near the muzzle. There were a number of differences between the Beals model and the later production “Old Model” 1861 and “New Model” 1863 revolvers. The most obvious differences were the “high spur” hammer and the fact that frame concealed the barrel threads at the rear of the barrel. Shortly after the “Old Model” 1861 went into production, this feature was eliminated and a relief cut in the frame revealed the threads at the barrel’s end. The system of retaining the cylinder arbor pin via the loading lever evolved as well. While the Beals revolver required the lever to be lowered to withdraw the pin, the Model 1861 included a relief cut in the top of the lever that allowed the pin to be pulled forward with the lever in its upright and locked position. The Beals model did not have safety notches on the rear of the cylinder, allowing the hammer to be safely dropped and locked between cylinder chambers, and this feature was added to the Model 1861 and 1863 revolvers. Other minor evolutions occurred as well, including making the loading lever slightly larger and more robust. As the Beals was the first of the large frame martial Remington revolvers it underwent some changes and improvements during its production. Author Donald Ware in his book Remington Army and Navy Revolvers, 1861-1888 actually breaks the Beals Navy down into four different types, based upon minor changes in features, most of which are barely noticeable. The most obvious feature of the earliest, Type 1, revolvers is the use of the “single wing” arbor pin. Later production guns (somewhere between #200 and #400) start using the standard “double winged pin”. Another change that is fairly obvious is in the loading lever catch. Initially a dovetailed, Colt style latch stud is present under the barrel. Over time this evolves to a rounded stud that is threaded into the bottom of the barrel. Numerous small changes occurred in the dimension of small parts, some internal part improvements and even the nature of the hammer checkering during the course of production of the four variant “types’ of the Beals Navy. To the collector, the only really important variation is the early “single wing” Type 1 guns, as they are so incredibly rare.

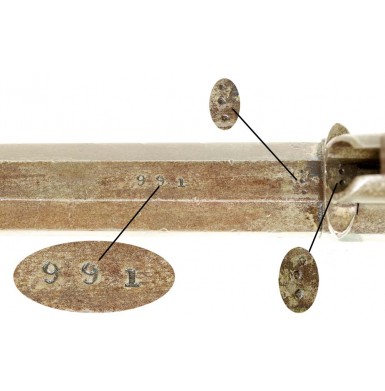

Offered here is a VERY GOOD condition example of a Remington-Beals Navy Revolver, which has the very low, three-digit serial number 991. According to Mr. Ware’s book this would make this gun a “2nd Type” based upon serial number, but it has some interesting minor features that suggest it was some type of transitional model that tested one of the possible improvements to the loading lever catch. The gun has matching serial numbers stamped on the bottom of the barrel, inside the grip frame under the left grip panel, and written in pencil inside both grips. The only other part that is usually serial numbered, the triggerguard, was not removed for examination. The gun also bears some somewhat unusual punch-dot assembly marks, which suggest this was not your standard “off the assembly line” gun. Three punch dots are present on the bottom of the barrel (concealed by the loading lever), on the winged cylinder arbor pin, on the rear face of the cylinder and on the bottom of the very interesting loading lever catch. The side of the loading lever is marked with four punch dots that appear to represent an error or a loading lever from the experimental transitional gun that was marked with four rather than three dots. The top of the barrel has the usual two-line Beals marking that reads:

BEALS’ PATENT. SEPT. 14. 1858

MANUFACTURED BY REMINGTONS’ ILION. N.Y.

Other than the serial numbers and punch dots already mentioned, there are no other markings. The most intriguing feature of the gun is the overly engineered loading lever catch that is installed under the barrel. The 1st Type catch was simply dovetailed into place and looked very much like the flat catch found on Colt revolvers. The catch that evolved on the Beals Navy after the 1st pattern was a rounded lug with a cut out for the lever that was threaded into the barrel. This catch seems to be an evolution towards that catch. This catch is a faceted, wedge-shaped lug that appears to be secured to the bottom of the barrel by a large round pin. In fact, it almost looks like the large pin could be the round catch used on later guns, with a protective cover around it. The purpose appears to be two-fold in that it protects the catch lug and the faceted front would make it easier to holster the gun without the catch lug “catching” on the holster. It looks like a good idea in theory, but was probably found unnecessary and certainly increased production costs as the machining of the lug surround was probably very time consuming. This appears to be the classic example of an over-engineered idea that was subsequently simplified. The other non-standard feature is the hammer spur. While Remington Beals Navy revolvers had higher and straighter hammer spurs than later production guns, this one is even higher and straighter than is usually encountered. The hammer shows no signs of repairs, and is most certainly not a replacement. In fact, it retains some traces of its original case coloring. It simply appears to be another experimental feature to try out on the revolver, along with the special loading lever catch. Interestingly, as production continued, the hammer spur evolves toward the shorter, more curved spur found on the M-1861 and M-1863 revolvers.

As noted the revolver remains in VERY GOOD condition. It is crisp and sharp throughout with clear markings, but does not retain any of the original finish. The metal has a mostly smooth, grayish-brown patina with scattered oxidized freckling and some minor flecks of surface roughness, as well as some lightly scattered pinpricking. A few tiny areas of light pitting are present as well, primarily around the cone recesses, chamber mouths and on the frame forward of the chamber mouths where the hot gasses eroded some of the metal. The bore of the revolver is in VERY GOOD condition as well. It is slightly dark, showing some oxidation, and light pitting along its length, but retains crisp rifling throughout. The revolver remains in mechanically excellent condition and functions correctly in every way. The revolver times, indexes and locks up exactly as it should. The loading lever functions smoothly and locks into place securely. Interestingly, the lever catch is slightly loose and does rotate slightly. The cones (nipples) all appear to be original and although they show some wear and light battering, remain fully functional. The original German silver cone front sight is in place on the top of the barrel near the muzzle and remains fully height and is not worn down. The two-piece smooth walnut grips remain in VERY GOOD condition as well. They are solid and are free of any breaks, cracks or repairs. The grips appear to have a small amount of added varnish on their exterior. On their interiors, both grips are pencil numbered to the gun. The grips do show the usual assortment of scattered bumps, dings and handling marks, but show no abuse.

Overall this is a very nice example of an early, three-digit serial number, Remington-Beals Navy Revolver. The gun has a couple of interesting transitional, or possibly experimental, features and also has some uncommon assembly marks. All of the usual markings remain crisp and clear and the gun is all matching throughout. As nearly 80% of the Remington-Beals Navy Revolvers saw Civil War service, this would be a wonderful addition to a collection of secondary martial Civil War handguns. It would also be a great addition to any Remington handgun collection and might be a more important prototype gun than I realize, making it an even more important addition to an advanced Remington collection.

SOLD