Experimental Oval Bore P-1853 Enfield - ex Hythe Collection

- Product Code: FLA-3254-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

In January of 1852 the British Board of Ordnance began taking the first tentative steps towards designing what would eventually become the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Musket. These movements were not without some hesitancy, as the Pattern 1851 Mini” Rifle had been officially adopted only the previous year, and arms were just starting to be delivered by the contractors. Even though the P-1851 was the first rifled arm for general issue to the British military, officially ending the era of the smoothbore musket in English service, it was a design that was obsolete prior to its adoption. The large, .708” caliber was an anachronism of a by gone age, and various Continental armies had been experimenting and even issuing smaller bore rifled arms since the latter part of the previous decade. It was this knowledge that a smaller bore rifle musket was necessary in order to stay competitive with the armies of Europe that spurred the Board of Ordnance to start experimenting with “small bore” rifles. The first two trials rifles to test the basic theory of a reduced caliber, elongated bullet design were ordered to be set up at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock (R.S.A.F.) in January of 1851 and were for all practical purposed simply smaller bore pattern 1851 Mini” Rifles. However, these guns were only intended to demonstrate to the English military what had already been proven on the European continent; the “big bore” military musket was dead and the “small bore” rifled musket was the new heir apparent to the throne of infantry small arms. At that time, the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield was not the thriving manufactory that America’s Springfield or Harper’s Ferry arsenals were, and the arms produced there were made essentially by hand from a mixture of government made and contractor delivered parts in much the same manner as the Brown Bess muskets had been “set up” at the Tower of London nearly two centuries earlier. It would not be until 1856, in the wake of the Crimean War that the R.S.A.F. would be modernized and outfitted with machinery from America, allowing it to operate on the “American System” of manufacture, using interchangeable parts on an assembly line. As a result, the design of what would become the Pattern 1853 Enfield was in some respects left up to the powerhouses of the British arm manufacturing community, namely Westley Richards, Charles Lancaster, James Purdey, Henry Wilkinson and W.W. Greener; all of whom are household names to any student of English arms from the period. As Dr. C.H. Roads so artfully puts it in his seminal book on the subject The British Soldier’s Firearm - From Smoothbore to Smallbore 1850-1864:

“all agreed to construct and submit the best military rifles their ingenuity could fashion.”

The arms submitted by these makers took a variety of designs and provided the Board of Ordnance the ability to further investigate such technical nuances as types of rifling, as well as rates of rifling twists, patterns of rear sights, bullet designs, etc. As a sort of “control” these trial arms were often compared with known quantities like the Pattern 1851 Mini” Rifle and the Brunswick Rifle, and at times special versions of these current issue rifles (usually only one or two) were produced at Enfield to test a specific design principle, while leaving all other factors constant. An example being the reduced bore P-1851s produced in January in of that year in .635” caliber versus the standard .708”, to test the basic principle of a smaller bore diameter. The submissions by the various makers were all different calibers and with different patterns of rifling and each used a bullet of their own design, with only constant that the bullet weight was about one ounce, a weight considered minimal for an effective infantry musket. Lancaster’s submission was his “oval bore” design. This was a mechanical rifling system that from all appearances was a smoothbore design. However, the bore was very slightly oval in cross-section with a minor axis of .543” and a major axis of .557” at the breech, which was slightly reduced to .540” and .55” at the muzzle. The bore itself twisted along the length of the barrel, creating mechanical rifling similar to the systems that would be subsequently patented by Sir Joseph Whitworth and Westley Richards. The pitch of the riling also increased along the length of the bore, in other words the rifling spun slower at the breech and more quickly at the muzzle. The oval bore rifling performed very well in the trials, as did the five-groove design of Wilkinson and the 3-groove design submitted by Enfield. The result of these experimentations resulted in what would become the basic design specifications for the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle musket: a 39” barrel secured by barrel bands, with a .577” bore, rifled with 3-grooves with a 1:78 rate of twist, weighing in at slightly more than 9 pounds including the socket bayonet, which would incorporate a locking ring. It was further specified that the lock would include a “swivel” (stirrup) so that the mainspring did not bear directly upon the tumbler as it did in earlier designs. The specification regarding a rear sight remained somewhat open to discussion, as a number of designs had been submitted, several of which were quite good. Interestingly the rifling pattern was not completely established either, for although the initial specifications called for the three groove bore of Enfield design, the performance of the Lancaster and Wilkinson pattern rifling left significant doubt in the minds of the Small Arms Committee as to whether the correct decision had been taken as to the style of rifling to be use. A bullet design, which was a collaboration of William Pritchett and William Metford, was designed for use in the nominally .577 bores of the guns. In January of 1853 an order for 1,000 of these newly specified rifle muskets, 500 with one pattern or rear sight and 500 with another, was placed, in order to begin real field trials of the weapon. In the end the sight designed by Charles Lancaster became the rear sight that we are familiar with on the Pattern 1853 Enfield today. The result of the committee’s lack of confidence that they had “chosen wisely” regarding the rifling system was apparent in early 1853, when Wilkinson and Lancaster were both asked to submit Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets that conformed exactly to the pattern as was newly adopted, with the only exception being the rifling of the bores, which were to be of the two makers’ patent designs. In June of 1853 the trials of the three rifling systems began and the Lancaster oval bore shot better than either of its competitors. Initially, Lancaster aske to have his guns fired with his own cartridges that used specially sifted powder. However, it was soon discovered that the standard British military service load with standard service powder and the 530 grain Metford-Pritchett bullet shot better in the Lancaster gun than his own specially designed cartridge! Wilkinson insisted on using his own proprietary cartridge as well, and did not acquiesce to the use of the standard service load during testing. The result of testing the three systems at 500 yards, aimed at a 6” foot target resulted in the Lancaster rifling system placing all shots in a 4” group, while the Enfield rifling could only keep 75% of the shots on target at that distance. The Wilkinson system fared far worse, failing to reliably keep shots on the 6” target at 200 yards! The results of the testing were so promising that an additional 20 oval bore P-1853s were ordered from Lancaster for further evaluation by the Committee on Small Arms. In addition, it was decided to issue the available 3-groove P-1853s very sparingly, in the event that Lancaster’s system was eventually adopted over the Enfield 3-groove bore. To further indicate that the decision was not yet set in stone, it was ordered that all P-1853s in the production pipeline (some 20,000 contract arms) be made smoothbore, pending the final decision regarding the rifling pattern. The additional testing in August of 1853, shooting at distances of up to 800 yards, again showed the superior accuracy of the Lancaster design. However, two issues had raised concerns among the nay-sayers who supported the Enfield pattern rifling. The first was that the increasing spiral of the bore was complicated and difficult to produce, which would make it harder for the various arms contractors (as well as R.S.A.F.) to manufacture the Lancaster patent barrels. The second concern was that the relief at the breech, being slightly larger than the muzzle, could allow a loaded bullet to move forward when the arm was in service, leaving an air gap between the bullet and the powder charge. It was feared that this gap might create an unsafe situation resulting in increased pressures and a burst breech when the gun was fired. Lancaster subsequently performed tests with bullets that were not fully seated, which proved that this fear was unwarranted. However unfounded, the concern would affect further testing of the Lancaster system and in some ways conspired to help it fail. In late August five trial P-1853 Enfields were set up at Enfield with Enfield made, Lancaster patent barrels. The barrels had a minor axis of .577” and a major axis of .587”, and has the standard 1:78” rifling pitch. The barrels did not have the breech relief of the Lancaster made barrels, nor did they use progressive twist rifling, so the rate of twist remained constant through the length of the bore. These five rifles were tested against Lancaster’s submissions and were found to be sorely lacking, with the Lancaster produced rifles placing 99 of 100 rounds in a reasonable group on a 300-yard target, and the Enfield produced oval bores missing the target entirely 68 times at the same distance! Amazingly, this additional confirmation only resulted in additional testing, with the Board of Ordnance’s decision making process moving with all the speed of a receding polar ice cap! This fourth series of tests of the Lancaster system in 1853 again proved that the oval bore rifling was superior not only to the conventional 3-groove rifling employed at Enfield, but also to the Enfield made version of the oval bore. In these tests, the Enfield “oval bore” showed a tendency to “strip” after a significant amount of firing, what a modern shooter would refer to as the bore being “shot out”, with the rifling being worn beyond the point of serving its purpose. While the Lancaster made rifles did not show this tendency, it was implied that since this defect existed in the Enfield made arms, that “production quality” oval bore rifles, not produced with the same precision as Lancaster’s trial rifles, would suffer the same fate. Thus, a fifth set of tests were performed in November 1853, this time eliminating the Enfield made oval bores and once again putting the Lancaster oval bore in a head-to-head competition with the 3-groove Enfield. This last series of tests for 1853 showed that even Lancaster’s well-made guns, after a significant amount of firing, began to “strip” as the Enfield made versions had. The report noted that no visible (or even measureable) deterioration was noted, but that after repeated firing the accuracy of the guns gradually eroded. It appears that the Small Arms Committee was performing the tests with the same five trials rifles that had been supplied that summer, and it was likely at this point that thousands of rounds had been fired through the guns. Amazingly, this report resulted in a new series of tests in early 1854. This sixth test required more than 1,000 rounds to be fired from a single Lancaster oval bore rifle musket versus a standard Enfield P-1853. As had been discovered in the final testing at the end of the previous year, the Lancaster system began to “strip” and the accuracy degraded over time. The reason for the failure could not be discovered, and as the oval bore system was so much more accurate than the 3-groove system when the bore was new, the supporters of Lancaster’s design lobbied for another test (the seventh) in February of 1854, with the results being the same. At this point, it appears that serious pursuit of the Lancaster rifling system by the Small Arms Committee was abandoned. However, only a year later, Lancaster’s design was adopted for limited production and issue to the Royal Engineer Corps, as the Pattern 1855 Royal Engineer’s Carbine, or more commonly as the Royal Sappers & Miners Carbine, with Lancaster’s oval bore. So, as we can see the oval bore concept was far from dead and still had several supporters with the small arms and ordnance communities. In a continuing attempt to try to improve upon the basic design of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle musket, various trials continued at the School of Musketry at Hythe, under the direction of Colonel Hay, the commander. Very often these trials involved only one to two experimental examples of an arm, set up at Enfield for the express purpose of testing a specific theory about the performance of one particular feature. The testing performed by Colonel Hay resulted in several recommendations regarding the current service pattern Enfield rifle musket. These recommendations included reducing the length of the butt by 1” to change the length of pull from 14” to 13”, changing the location of the rear sight to improve the ability of a solider to easily focus upon it, changing the number of grooves in the rifling from 3 to 5 and changing the rate of twist from 1:78” to a much faster 1:48”. Many of these suggestions were never adopted for the Pattern 1853 Enfield in service (although the length of pull was eventually shortened), but were adopted for use in subsequent versions of the Enfield “short rifle” and were incorporated into Colonel Hay’s “Hay Pattern” Enfield “medium Enfield” design. While the Hay Pattern was never officially adopted by the Board of Ordnance, it was a popular design for military match target shooters and saw reasonably successful sales to the New Zealand military. It appears that during 1856, after the adoption of the Lancaster Patent rifle for use by the Royal Engineers, that Colonel Hay required that two P-1853s be set up at Enfield with the Lancaster oval bore to test the effects of fouling upon the design, versus conventional rifling. Interest in the overall Lancaster concept had not subsided, and even though the Small Arms Committee had abandoned serious consideration of the oval bore in 1854, the elliptical bore design was once again involved in official trials. In late 1861 the Ordnance Select Committee had five 39” oval bore rifles set up at Enfield, and this time used Lancaster’s progressive twist system and allowed for .002” of relief at the breech. These newly set up arms were produced with a major bore axis of .580” and a minor bore axis of .572” (.582” and .574” respectively at the breech). These 1862 trials revealed the superiority of the oval bore design in accuracy and in its tendency to not foul as badly as the 3-groove rifling did. In fact, the testing showed that the slow twist, 3-groove rifling was probably as “inefficient” a design as could have been chosen, with Colonel Hay’s preferred 5-groove, 1:48” pitch rifling proving superior, as he had already discovered during his own testing. However, it appears that the “die was cast” as it were, and it was simply too late to change, and even in 1862 it was apparent that soon a smaller bore rifle of a breechloading pattern would be the future of the British military, and that the days of the muzzleloading cap lock were coming rapidly to an end.

Offered here is an exceptionally rare Lancaster’s Patent Oval Bore P-1853 Trials Rifle from the collection of arms previously held at the School of Musketry at Hythe. The gun is accompanied by a copy of a 1978 dated, type written, appraisal from S. James Gooding of Museum Restoration Services, addressed to Mr. Lee F. Murray, Chief Curator of the Canadian War Museum. The appraisal details sixteen British military trials firearms, most of which originated from the collection of the School of Musketry at Hythe. The arms were de-accessed following the end of World War II, and were acquired by a Canadian arms collector, James Adams of Oshawa. The collection was subsequently sold to another Canadian collector, a Mr. Donald Thomas, who offered to sell the collection to the Canadian War Museum in 1978. It is not clear from this appraisal if the Canadian War Museum ever accepted Mr. Thomas’ offer to acquire the collection, but this rifle is detailed as item number 1 in Appendix A of the document. The description in Appendix A reads in full:

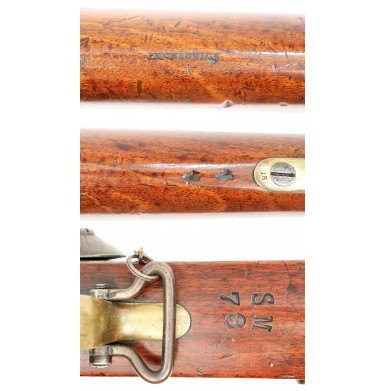

Lancaster rifle. Allegedly one of two made to test the reduction of fouling in a smooth-bore rifle. An experimental carbine exists in the Tower of London collection. The barrel is marked “Lancaster’s Patent.” The rear sight has not calibrations for elevation other than four file marks for short range firing. The lock is dated 1856.

Examination of the gun reveals that it is a text book example of the types of trial arms set up at Enfield during this period. The gun follows the basic lines of a standard Pattern 1853 Type I rifle musket, with a 39” round barrel secured by clamping bands of the Palmer pattern, a swelled shank ramrod with a small tulip shaped head, a 14” length of pull and standard brass furniture. The two primary deviations from the norm are the “smooth” oval bore and the presence of an ungraduated rear sight that is quite similar to the sight used on the Pattern 1851 Mini” Rifle. The breech is marked LANCASTER’s PATENT with a small stamp, forward of the nocksform and behind the rear sight. The nocksform itself is marked with a (CROWN) inspection mark, a (CROWN) / E / 5 Enfield inspection mark, a single punch dot mark and with the fraction 1 / 2, indicating that this is number “1” of “2” guns. The left breech bears a pair of British military proof marks, a (CROWN) / VR) and a (CROWN) / (CROSSED PENNANTS). These are not the types of proof and inspection marks found on a “production” military P-1853, and are indicative of the special, trial purpose of the gun. The bottom of the barrel is marked with an 18 and the matching number appears on the breech plug. The bottom is also stamped ENFIELD and with the inspection marks (CROWN) / E / 1 and (CROWN) / E / 8. Additionally, the initials JT are found under the barrel. The lock is clearly marked with a (CROWN) / VR) to the rear of the hammer and 1856 / TOWER forward of the hammer. A small, sideways “Crowned Broad Arrow” is found on the lock along with a (CROWN) / 17 inspection mark. The interior of the lock reveals that is was produced by Wolverhampton contractor Joseph Brazier and it additionally bears the internal inspection mark (CROWN) / B / 21). The obverse butt is stamped with an Enfield roundel that reads simply: “ R S A “ ENFIELD in a circle around a blank center. The toe of the stock is marked JAs CHADWICK, who served as an inspector at Enfield during the period. Forward of the triggerguard, the belly of the stock is deeply stamped SM / 78. It is my belief, based upon the accompanying paperwork, that this mark indicates the gun originated in the collection at Hythe, and that this stamp means School of Musketry #78; the Hythe collection inventory number. It is not clear why a Pattern 1853 Enfield set up in 1856 would have “Type I” barrel bands, rather than the solid spring retained bands of the “Type II” which was in production from late 1855 through 1858, but it may have afforded an opportunity for Enfield to use up some older parts on hand, and the trial was to investigate fouling of the oval bore, not to determine what type of barrel bands should be adopted.

The gun is in VERY FINE condition and is absolutely gorgeous. All markings remain crisp and sharp and the gun has a wonderfully untouched and unmolested appearance throughout. The barrel retains about 30% thinning blued finish, which is somewhat streaky in appearance and has faded, dulled and oxidized to a very attractive smooth, plum-brown patina. The bottom of the barrel, where the stock has protected the finish, retains about 85% of its original bright blue. The barrel is smooth throughout with no pitting to speak of, other than a thumb-sized patch of lightly oxidized roughness just above the stock line on the reverse between the lower and middle barrel bands. This is just above a slightly larger patch of discoloration on the stock itself, and it may indicate that this area got wet at some point in time, resulting in the oxidized patch on the barrel. Otherwise, the barrel shows only some lightly freckled surface oxidation scattered through the remaining finish and patina and some very lightly scattered pinpricking around the breech, bolster and muzzle area. The oval bore remains bright and sharp and shows no pitting or significant wear. The bore shows an evident twist when a light is dropped down it, with the minor machine marks and fine striations making it quite apparent. I do not see any indication that the pitch of the rifling is anything but consistent, so it does not appear to have the progressive spin found on Lancaster produced arms, and the trial arms from 1861-1862. The major axis of the bore measures .589” and the minor axis measures .572” by my calipers, and assuming the breech is relieved between .001” and .002” it would measure approximately .59” and about .573”. Roads notes another trials rifle that is in the collection of the British Ordnance Department (not an oval bore) that is approximately .594” and is rifled with 5-grooves. As the Small Arms Committee was still experimenting with the appropriate bore diameters for the Lancaster design in 1854 and used yet a different set of measurements for the 1862 trials, it does not surprise me that these dimensions are slightly different than some of the other examples noted in the various trials. The lock of the gun is mechanically EXCELLENT and functions perfectly on all positions. The lock has a medium pewter gray patina with some darker mottling that hints at its original case colored appearance. The lock shows some lightly scattered pinpricking and minor surface oxidation, primarily at the front and rear of the lock plate. All the markings on the lock remain very crisp and clear. The rear sight is ungraduated, as previously noted and is basically the same as is found on the Pattern 1851 Mini” Rifle and some examples of rifled and sight British Pattern 1842 Muskets. The sight is in crisp condition and functions correctly. Dr. Roads notes other examples of trials rifles with the same pattern of ungraduated sights in his book, some of which are pictured. It can be assumed that these were also left over parts being used up, as the trial was not about accuracy in the case of this gun, but about fouling of the bore. It also seems reasonable that since a specific bore diameter had not yet been established for the oval bores, no data was available for graduating the rear sight and it would have to be graduated during testing, if needed. The original Palmer’s Patent barrel bands are inspected with (CROWN) / # marks, and all three retain their original washer style screw protectors at their ends. The bands are all a medium plum-brown color with strong traces of original blue present under the smooth patina. The original upper sling swivel is in place on the upper barrel band, as is the lower swivel on the triggerguard. An original leather covered iron snap cap (nipple protector) is attached to the lower swivel by the correct teardrop shaped brass chain and iron split ring. The original ramrod is in place in the channel under the stock. The swelled shank, tulip shaped rod is inspected with a (CROWN) / B / 12 mark on its shank. The brass furniture has a medium golden patina and remains very attractive. The stock of the gun is in about FINE to VERY FINE condition and remains solid and full length. The stock is free of any breaks, cracks, chips or repairs. It does, however, show numerous minor dings, mars, bumps and handling marks from use and storage. These are widely scattered with the most obvious being present around the wrist area. The wood to metal fit is very fine throughout the entire gun.

Overall this is a really wonderful condition example of an Experimental Lancaster’s Patent Oval Bore P-1853 Enfield Rifle Musket, made at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock in 1856 for testing at the School of Musketry in Hythe. The gun come with strong written provenance, but its configuration and markings certainly confirm what it is. The gun was made at Enfield and bears the expected Enfield inspection marks for a non-production model, is clearly marked as “1 of 2” on the nocksform, and has the School of Musketry collection number “78” clearly stamped in the wood forward of the triggerguard. While Lancaster Patent Oval Bore Sappers & Miner’s rifles are quite scarce in their own right, experimental oval bore P-1853 Rifle Muskets are made of “un-obtanium” and simply do not exist outside of institutional collections. If you are an advanced Enfield collector, have a particular interest in the School of Musketry at Hythe or have a real passion for Lancaster’s oval bore designs, this is a “must have” piece for your collection that you almost certainly never have another opportunity to obtain. As a lover of historic English arms, and Enfields in particular, this is one gun that I would love to keep myself. It deserves to be added to a world class collection, where its rarity, unique features and condition will be truly appreciated. In a perfect world, it might end up in a museum collection, where other collectors and researchers will have the opportunity to study it. With the fate of number “2 of 2” unknown, you don’t want to miss your chance to own a potentially one-of-a-kind experimental Enfield Rifle Musket.

Provenance: School of Musketry at Hythe collection, James Adams (Canada) collection, Donald Thomas (Canada) collection, an advanced collection of 19th century British military arms from upstate New York. A copy of the December 1978 appraisal from Museum Restoration Services that describes this gun is included with the firearm.

I am indebted to Dr. Roads’ book The British Soldier’s Firearm - From Smoothbore to Smallbore 1850-1864/b> which was indispensable in the preparation of this description.

SOLDTags: Experimental, Oval, Bore, P, 1853, Enfield, ex, Hythe, Collection