Excellent & Extremely Rare Wilson's Patent Rifle

- Product Code: FLA-2094-SOLD

- Availability: Out Of Stock

-

$1.00

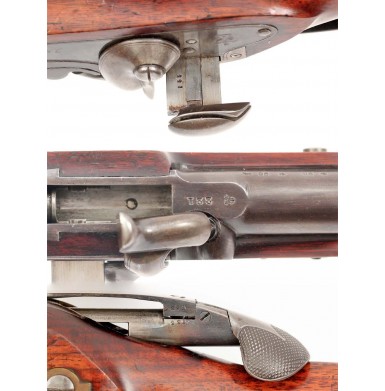

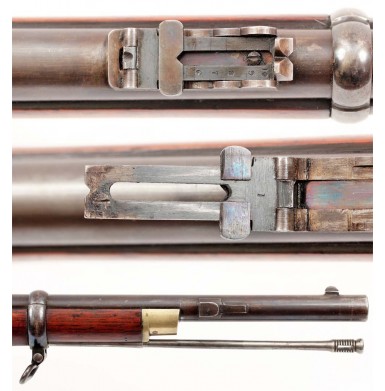

The Wilson Patent Breech Loading Rifle is one of the rarest and most sophisticated of small arms to be imported by the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Thomas Wilson was an engineer and inventor and held no less than 25 British firearms patents, which he registered between 1855 and 1868. Only briefly, during the years 1861-1862, does Wilson appear in English directories as a “Gunmaker”. While pursuing that trade he was located at 45 Church Street in Birmingham. However, Wilson’s limited time as a manufacturer of firearms belies his significant influence on firearms design and development. His patented designs were utilized by many English gunmakers, and while firearms of his own actual manufacture are extremely scarce, the use of many of his designs was common during the mid-19th century. British patent number 1318 of 1859 covered Wilson’s Breech Loading Rifle. It was for a percussion ignition, breech-loading rifle that was ingeniously simple and extremely sturdy. A simple “bolt” was located at the breech end of the barrel, which was secured by a transverse wedge, similar to an extremely oversized Colt pistol wedge. To load the gun, the wedge was drawn outward, away from the lock plate. When pulled out sufficiently, the wedge freed the simple bolt to be drawn backwards and exposed the chamber for loading. The bolt had a pivoting, fishtail shaped, checkered piece at its rear that gave the operator a firm grasping area for opening the bolt and a large target to slam the bolt closed with, when using the palm of his hand. A combustible cartridge was inserted in the chamber and the bolt slammed home to seat the cartridge. A greased felt wad in the bottom of the cartridge insured the chamber sealed completely and did not leak gas. The locking wedge was then pushed back into the bolt, securing it. At this point the hammer could be placed on half cock, and a percussion cap placed upon the cone (nipple). The rifle was then fired like any traditional cap lock. The placement and design of the wedge insured safety, as the hammer had to be in the fired position for the wedge to be moved. When the wedge was withdrawn (or not completely seated into the bolt), the hammer could not be moved at all and was blocked into fired position. This eliminated the potential for an accidental discharge while loading the rifle, or the firing of the gun without having the bolt completely in battery. Wilson produced the arms in two calibers, 28 Bore (.551) and 56 Bore (.451), and in three patterns: rifle musket (39” barrel), rifle (33” barrel) and carbine (21” barrel). All variants were rifled with 5-grooves, which made one complete turn in the length of the .551 caliber arms (regardless of barrel length) or 1 turn in 21” for the .451 guns. The guns were offered in either iron or brass mountings, and the guns averaged between “8 and “10 each, depending on mountings and barrel lengths. Brass mounted guns were less expensive than iron mounted ones. As with any major firearms innovation, the goal of Wilson’s invention was to obtain military contracts that could be very profitable. In fact, initial press regarding his breechloading rifle suggested that his design was superior to both the Westley Richards and Terry’s patent breechloaders, and that the simplicity of the mechanism might enable the British Ordnance Department to easily convert their existing stores of P-1853 rifle muskets to breechloaders. In an attempt to secure the potentially lucrative Ordnance Department contracts, Wilson submitted one of his percussion breech loading rifles to the Ordnance Select Committee for testing. As noted in their August 1, 1860 report, they found the mechanism ingenious and reported upon it positively, but found the accuracy of the arms left much to be desired. The problem was the ammunition. As the beech was sealed with a greased felt wad in the bottom of each cartridge, the wad remained in the bore after the cartridge was fired. This meant that the next cartridge fired left the bore with the former cartridge’s wad stuck to the nose of the bullet. This resulted in erratic accuracy, as the wad often interfered with bullet as it left he muzzle, causing it to heel and yaw and reducing its aerodynamic design. However, the Ordnance Committee was so impressed with the mechanical part of the design that they requested that Wilson alter two P-1853 Enfield rifle muskets and one Whitworth rifle to his system for further trials. The P-1853’s were fired for accuracy at 300, 500 and 800 yards prior to the alteration, so their accuracy after the alteration could be compared to that of their original muzzle-loading accuracy. Again, the same problem reared its ugly head, and the March 26, 1861 report from the committee noted that, “the wild and capricious shooting of the converted Enfield is mainly owing to the action of this wad on the apex of the bullet, immediately on the latter leaving the barrel.” The committee further noted that the accuracy of the Whitworth was less impaired, and they attributed this fact to the smaller caliber, faster rate of twist of the rifling and the longer bullet. These results may be why Wilson only offered his arms in calibers smaller than the typical British 25 Bore of the period (.577). Wilson never did completely give up on obtaining British Ordnance contracts, as he submitted 6 altered P-1853 Enfields for the breech loading rifle trials in 1864, but although his design again received high scores, the lack of accuracy due to the ammunition design resulted in the Snider system being adopted for the alteration of British military arms. Interestingly, Wilson held patents that in his words “anticipated” the Snider system, and he sued the War Office for “5,000, but agreed to a settlement payment of “500, which suggests that the War Office certainly felt that his claim had at least some merit. With the rejection of his design by the Ordnance Select Committee in early 1861, Wilson proceeded to pursue sales with the newly formed Confederate States of America. It is not clear exactly how many Wilson breechloading rifles were obtained by the Confederacy, but to date only seven Wilson “short rifles’ of military configuration are known to exist. Three are iron mounted, 56 Bore (.451) rifles, and have an “A” prefix before their serial numbers. The highest known serial number being A84, suggesting that this series of rifle may have only been 100 units. These guns are dated 1860, and have been arbitrarily termed “early” Wilson rifles. A single, 28 Bore (.551) caliber rifle is known. It is brass mounted, has the serial number 221, without a prefix, and is dated 1861. It has been arbitrarily termed a “transitional” Wilson, although it is likely a concurrent production rifle with other .541 caliber rifles, simply in a different caliber. The final three rifles known are also brass mounted, but are again 56 Bore (.451), and are dated 1863. They have been arbitrarily designated “late” rifles. These rifles have serial numbers that begin with “2A”, suggesting another production series from the original “A”, and have serial numbers in the 50XX range. These numbers far exceed the total output of Wilson breech loading rifles (both by himself and other makers), which is believed to be a few hundred at most, including a small order of carbines for Tasmania, placed in 1864. The serial numbering system may have been allocated in blocks, much like Adams revolvers, with certain makers receiving certain blocks of numbers to work within. This made tracking of patent royalties easier. As Wilson himself only produced a very limited number of guns over an approximate time frame of two years, this would easily explain the odd 5,XXX serial numbers. The prefix system may refer to the type of arm, with “A” series guns being .451 and iron mounted, “2A” guns being .451 and brass mounted, and the no prefix arms being .551 and brass mounted. As no iron mounted .551 caliber rifle is known, there is no way to verify what the prefix would be on that gun (if such a gun did or does exist), and if it was indeed a different designator, supporting the above theory. Of the extant examples, the dates on all of the .451 rifles are stamped on the lock, while the single .551 rifle dated 1861 has an engraved lock plate. All of the arms follow the basic design of the British Pattern 1856 & P-1858 rifles, with the exception of the breechloading mechanism. The rifles have 33” barrels with rear sights graduated to 1,100 yards. Sling swivels are located on the upper barrel band and either on the rear of the triggerguard tang or in the toe of the stock line of the first two patterns of rifles and on the front of the triggerguard of the late pattern. The rifles have lugs on the right side of the barrel to accept a saber bayonet. While some authors have claimed that the rifle took a P-1859 Cutlass bayonet, this bayonet, with the muzzle ring sized to fit the P-1858 Naval Rifle, is too big for the muzzle of the Wilson rifles. The Wilson guns took standard P-1856 saber bayonets. The early and late pattern arms have lugs without a lead, while the “transitional” rifle has a keyed lug, designed to accept a P-1856 Type I saber bayonet. All of the rifles are marked T WILSON’s / PATENT on the top of the bolt and have standard Birmingham commercial proofs.

While no official Confederate order for Wilson rifles has yet been discovered, correspondence and other period documents indicate that at least a few of the rifles were purchased and delivered to the Confederacy. According a sworn statement, made by Archibald McLaurin, agent for the firm of J. Scholefield, Sons & Goodman in New Orleans, on July 10, 1862, the blockade runner Bamberg was carrying a sample Wilson’s breechloading rifle, destined for that firm’s showroom. McLaurin specifically refers to the gun as a “pattern rifle”, and noted that at the time of his interrogation by General Benjamin Butler, the rifle was still in Havana and had not (to his knowledge) reached the Confederacy. The Federal Blockading Squadron may well have captured the rifle after it finally left Havana. Additional documentation comes from an April 23, 1863 letter from CSN Commander James North to G.B. Tennent of Courtney, Tennent & Company of Charleston. In the letter, North complains about the tight fit of the bayonet on sample Wilson rifle that he had examined. North goes on to say “If I have not ordered 200 rounds of ball cartridges to each rifle, you will please do so for me. Get me the form for making them, also the receipt for lubricating the wads.” This suggests that at least some Wilson rifles were in use by the Confederate Navy as the not only needed ammunition for the rifles, but also the forms for making the cartridges in the south, and the formula for the wad lubricant. It would not make sense for the Confederate Ordnance Department to go to the trouble of obtaining the material to produce patent cartridges that could only be used in Wilson rifles, if there were not a number of the guns in service. A catalog from the February 11, 1880 New York US Ordnance Department sale held in New York lists “1 Enfield, altered Wilson’s, caliber .577, unserviceable, broken.” It is not clear if this listing was indeed a.577 Enfield altered by Wilson (possibly submitted when the US was trying out breech loading designs), or if the caliber was given incorrectly, and this was really a captured southern purchased Wilson rifle. We will probably never know. The seminal work “Firearms of the Confederacy” by Fuller & Steuart note that some Wilson rifles saw service in the defenses of Charleston. This seems possible, as Courtney & Tennent of Charleston appear to have delivered at least some of the rifles.

This Wilson’s Patent Breech Loading Rifle is the finest extant example known, the only example of a “transitional rifle” known, and I firmly believe is the “pattern rifle” referred to by Archibald McLaurin in his testimony. The gun is in absolutely stunning condition, rating EXCELLENT throughout. The gun first came to light in 1952, when John George purchased it from a collector in Portland, OR, for the princely sum of $70.00. At that time, the gun had a paper label on the stock which read in large script US ORD DEPT WASH DC. When Mr. George purchased the gun he soaked the label off the stock, folded it and placed it under the upper barrel band for safekeeping. Unfortunately, over the ensuing 60 years, the label completely disintegrated, leaving only some remnants of paper under the barrel band, pressed against the stock. The majority of the remains of the label were lost when the gun changed hands in 2007, selling from Mr. George to another collector privately. At that time it was partially disassembled to document any markings, and a piece of oily paper marked “US’ was found under the band. I believe that this may be McLaurin’s “pattern rifle” because of the condition of the gun, the documented story about the Ordnance Department tag, and the fact that this is an actual Wilson produced Wilson rifle. It appears that most Wilson pattern arms were actually produced by other contractors, but McLaurin’s testimony infers that the pattern rifle came from Wilson himself. The gun is clearly and crisply marked on the lock with a typical (ENGLISH CROWN) to the rear of the hammer and with the engraved date 1861 forward of the hammer. The top of the bolt is clearly engraved T. WILSON’s / PATENT. The breech is marked with Wilson’s trademark, a (CROWN) / TW, and with the serial number 221. This same serial number appears on all of the components of the bolt and on the bottom of the breech wedge. The fishtail operating lever at the rear of the bolt is exquisitely hand checkered and is a real work of art. The top portion of the bolt retains the majority of its bright fire blued finish, which is starting to fade and turn a purplish-brown patina. The balance of the bolt body retains much of its case hardened mottling. The lock and hammer retain about 95%+ of their original case hardened finish, which is starting to tone down slightly and is not quite as vivid as it was 150 years ago. The lock and hammer show lovely mottled swirls of blue, purple and brown and are very attractive. The barrel retains about 90%-95% of its original rust blued finish, and shows only some minor fading and light finish loss along the high edges and contact handling areas. The left breech is marked crispy with the Birmingham provisional proof, definitive proof and definitive view marks, along with a pair of 28 gauge marks, which indicate the bore is .551 caliber. The saber bayonet lug near the barrel is the keyed variant for the P-1856 Type I bayonet and is marked with the mating number 1. This same mating number is present under the ladder of the 1,100 yard rifle rear sight. The lock functions crisply and correctly on all positions, and the Wilson’s patent breech loading system locks tightly into place and the bolt moves smoothly when the wedge is withdrawn. The bore of the rifle is NEAR MINT and is brilliantly bright with excellent five-groove rifling. Both original Palmer patent barrel bands are present, complete with their original screw protectors on the ends of the tension screws. Both original sling swivels are present as well, the upper on the upper barrel band and the lower screwed into the toe line of the stock. The original and correct ramrod is in place in the rammer channel, with its unique flared lip along the body of the rod to insure retention it the stock. This pattern would be revisited in the shape of the cleaning rods for Martini-Henry rifles. The brass furniture has a lovely, mellow, golden patina. The butt plate has a hinged compartment, which reveals two small holes in the stock for the storage of an oiler and a cleaning jag; neither of which are present. The stock of the rifle rates about EXCELLENT condition as well, and retains nearly all of its original finish. The stock is solid and free of any breaks, cracks or repairs. The stock does show a number of minor bumps, dings and handling marks from use and storage, but nothing worth noting.

Overall this is simply an outstanding example of what is likely the rarest of all Confederate import rifles. The gun is simply stunning and the photos do not do it justice. It would be absolutely impossible to upgrade this gun. In my mind this is almost certainly the pattern Wilson rifle that was in transit to New Orleans and was likely capture by the blockading squadron and spent most of the 19th century in a US Ordnance warehouse. When you take into account the quality of the gun, the condition, the paper label it bore in the 1950’s and McLaurin’s testimony, it all makes sense. This is a truly iconic piece, which deserves a place in an elite collection of Confederate long arms. You will not be disappointed with this opportunity to obtain such an outstanding, investment grade and extremely rare Confederate import rifle. A binder of research and period documentation accompanies this rifle.

SOLD